Cashflow Capitalist

Summary

- Ample economic research has shown that excessive debt, above a certain threshold of GDP, begins to drag down economic growth. US national debt is now well above that threshold.

- But ballooning debt, in itself, is not the fundamental issue. It is the result of the core problem.

- In the coming decades, the US economy will be asked to do the impossible: grow faster even while the government extracts more of its resources.

- There are no easy solutions. There are only painful trade-offs.

There are no solutions. There are only trade-offs.

—Thomas Sowell

Macroeconomic Thesis

In the past, on multiple occasions, I've written about how the United States' enormous national debt burden will slow economic growth going forward. Academic studies have demonstrated that, above a certain threshold of debt-to-GDP (ranging from 60% to 90%, depending on the study), government debt becomes a growing drag on GDP.

However, the problem is not really debt per se. Debt is a consequence of the problem, and it exacerbates the problem. But the fundamental issue is more straightforward, hiding in plain sight.

It's the reason why the European Union, with lower debt-to-GDP than the US, has actually experienced worse economic growth. It's the reason that aging developed economies across the world will continue to see more sluggish productivity and wage growth in the decades ahead.

In the past, I've fingered unproductive debt as the culprit behind waning economic growth, but there's another villain who deserves more of the blame. And that is unproductive government spending.

In what follows, I'll explain the (somewhat paradoxical) economics of why excessive government spending leads to slower GDP growth.

The Problem Behind the Problem

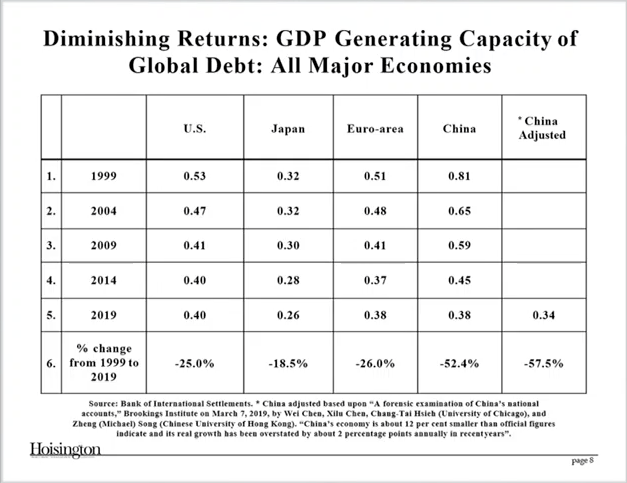

As I've written about elsewhere, there is a very simple way to measure whether government debt is productive or unproductive. Just look at the amount of GDP generated by each unit of additional debt. It may not work well during recessions, but it is informative during expansions and over long periods of time.

As I explained in The Monetary Death Spiral Is Accelerating, as global debt has exploded in the last half century, the GDP generating capacity of debt has steadily declined. Just looking at advanced economies in the last twenty years, we find the productivity of debt falling by one-fifth to one-half:

Source: Hoisington Investment Management Company

Each additional dollar (or euro, pound, yen, yuan) of debt is increasingly unproductive. The law of diminishing returns is taking effect.

My "Monetary Death Spiral" thesis, laid out in detail in the above cited article, explains my thesis for why this is. Aggressive monetary easing over the last three and a half decades has prevented normal market self-correction mechanisms from operating, and it has shielded the government from the normal consequences of overspending.

As interest rates have approached zero, all sorts of market, economic, and social distortions have manifested. These distortions have expanded economic inequality, weakened productive investment, spurred unproductive investment (or malinvestment), caused wage stagnation, and dampened economic growth.

Mainstream economics asserts that there is a government spending multiplier effect. That is, when the government spends by sending money to households, subsidizing healthcare or housing, or even paying out interest payments to American holders of Treasury securities, this leads to more consumer spending, which means more profits for businesses, more capital investment, more employment, higher wages, and so on in a virtuous cycle.

When the government spends by putting money into the private economy, it multiplies economic output more than would otherwise have occurred without it.

What this idea gets wrong is that last clause of the previous sentence: "more than would otherwise have occurred without it." That money has to come from somewhere. In fact, it can only come from two potential places: (1) taxation, or (2) private savings. Either it gets taxed from the income or wealth of productive individuals or businesses, or the savings of the private economy are used to buy government debt issuance.

Proponents of the government spending multiplier effect theory rarely attempt to measure the opportunity cost of government spending. That is, they point to the beneficial economic ripple effects of the spending without considering the potentially beneficial economic effects of allowing that money to remain under the control of private actors.

Would the money taxed from the incomes of taxpayers have been spent in an even more economically beneficial way if not taxed? Would the private savings have been used for more economically productive purposes if left in the hands of households and businesses?

During the Great Depression, economist John Maynard Keynes famously suggested that the government spend money on anything, even if unproductive, just to get money into the hands of consumers. Pay workers to dig a ditch, and if that doesn't provide enough economic stimulus, pay them to refill the ditch. It will result in a positive return on investment in terms of GDP.

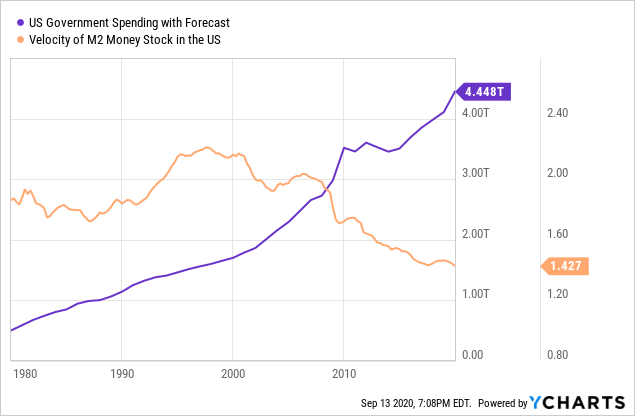

Over the last half century, that theory has not been borne out by the data. Instead, government spending has resulted in increasingly less economic dynamism. Notice how the impressive growth of government spending has negatively correlated with money velocity (the rate of turnover of a unit of currency in the economy) over the last two decades:

The core problem, then, isn't really the national debt. Rather, the debt is merely a symptom or consequence of the core issue, which is excessive unproductive spending.

Even if the United States managed to eliminate the fiscal deficit and run a balanced budget while leaving its current level and allocations of spending in place, the result as far as economic growth is concerned would be pretty similar.

In fact, it may even produce worse growth, because it would require much higher taxation.

This goes against the theory that the core problem is low tax rates. Certainly, tax rates may need to rise in countries like the US in the future in order to help fill the revenue gap. But debt-to-GDP levels are rising in almost all advanced countries around the world, both relatively high tax and relatively low tax nations.

That is because government spending as a percentage of GDP remains elevated across the developed world and will likely rise due to the COVID-19 recession.

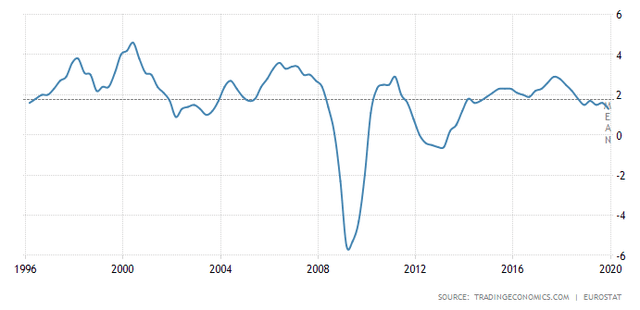

In the Eurozone, where tax receipts make up a much higher share of GDP than the US (a little over 40%, on average), government spending has vacillated between 45% and 51% of economic output for 25 years.

The average EU fiscal deficit during that period was ~2.5%, compared to the US's slightly larger ~3.0% average deficit over the same years. During that timeframe, EU GDP growth has persistently weakened, making lower highs and lower lows:

Source: Trading Economics

Source: Trading EconomicsThe US annual GDP growth rate unsurprisingly tracked that of the EU pretty closely over this time period, only with a higher average of ~2.5% versus the EU's ~1.9%. Meanwhile, EU government debt-to-GDP is lower than that of the US and has been lower since the early 2000s.

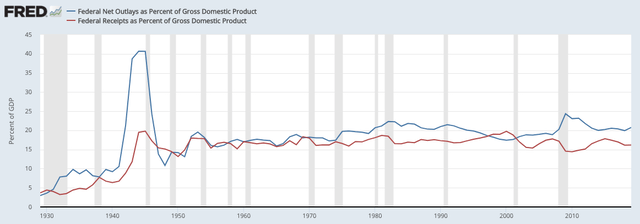

How about the United States? From 1969 to 2019, federal government spending has averaged 20.3% of GDP, while federal revenues (i.e. tax receipts) have averaged 17.4% of GDP, according to the Tax Foundation. See the chart below. The blue line is federal government outlays / spending, and the red line is receipts.

Source: St. Louis Fed

Notice a few things. First, prior to the Great Depression, the federal government was less than 5% of the economy, whether measured by spending or revenue.

The size of the federal government back then was roughly five times smaller than its average from 1947 to 1970 and almost six times smaller than its average from 1970 to 2019.

Second, since 1971, the federal government has run a fiscal surplus only four years: 1998, 1999, 2000, and 2001. This despite federal receipts holding steady around their average of 17.4% from the 1970s through the 1990s. From 2002 to 2019, however, federal receipts as a percentage of GDP have fallen to an average of 16.3%, while spending has remained slightly above its long-term average at 20.5%.

The point here is that debt is not the fundamental problem. The fundamental problem is excessive unproductive government spending. Significantly higher government spending as a share of GDP in European Union nations — more than double that of the US — goes a long way in explaining the discrepancy in economic growth between the two.

Currently, however, the US seems determined to narrow the gap in government spending with the EU. According to the CBO (via the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget), for the US federal government,

Revenue will total 16 percent of GDP in 2020 and average 17.5 percent over the subsequent decade – around its historic average of 17.4 percent. Spending will total 32 percent of GDP in 2020 and average 22.5 percent over the 2021-2030 window, above its historic average of 20.3 percent.

The problem is not debt in itself. Massive debt buildups in virtually all developed economies are really just a side effect of consistently spending too much money on unproductive uses. When put in these terms, it's easy to see how mounting national debt, beyond a certain portion of the economy, drags down economic growth.

By necessity, it results in some combination of (1) resources being extracted from the mostly productive sector of the economy (the private market) via taxation to pay the bills of the mostly unproductive sector (government) and (2) private savings being sapped to purchase government debt, thereby crowding out private investment.

In this sense, national debt loads can be seen not as an accumulation of debt capital that correspondingly increases the total assets of the nation. Rather, they are the cumulative effect of many decades of consumption brought forward in time. It is akin to the total balance on one's credit card after rolling a maxed out balance from one card onto another dozens and dozens of times.

For the most part, government debt has not been used to invest in infrastructure, basic research, education, or anything else that might result in a higher GDP than would otherwise have occurred if the money had remained in the private sector. It has not, on net, added assets to the national economy. Instead, federal spending is mostly used for purposes of current consumption — i.e. redistributing resources from taxpayer income/wealth and private savings to consumers.

What The Federal Government Spends Money On

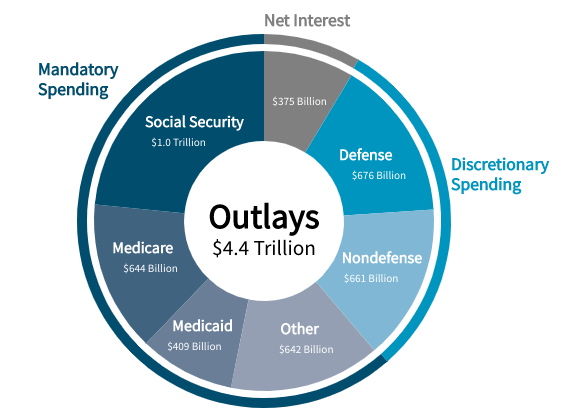

When we look at the federal budget, we find that the vast majority of it goes toward what I called above "current consumption" rather than long-term investment:

2019 Federal Outlays:

Source: Congressional Budget Office

The "Other" category of mandatory spending includes unemployment insurance, federal employee pension obligations, veterans' benefits, and various means-tested welfare benefits such as the earned income tax credit, SNAP program, etc. Only a minority of non-defense discretionary spending goes toward what might be considered investment.

When looking at federal government spending, it's important to distinguish economic arguments from moral arguments. Perhaps another way of expressing this sentiment is to differentiate between two questions: (1) What should we spend money on as a nation? And (2) what effects do our spending decisions make on the economy? The former is a moral question, the latter an economic one.

We must acknowledge that there are many examples of morally good yet economically unproductive uses of money. Taking time off work and flying across the country to visit family members may be both morally good and unproductive at the same time. Think also of money spent easing the pain of loved ones in their final months of life. Think of the resources expended caring for the mentally or physically disabled who will never be able to hold a job.

Not everything in life is about economic efficiency or productivity. Questions about the morality or proper scope of government spending are beyond the purview of this article.

However, it's also important to acknowledge that, in economics, there is no free lunch. There are no solutions, only trade-offs. It's crucial to understand those trade-offs in order to make more informed moral decisions. And for our purposes here, those trade-offs are necessary to understand in order to forecast macroeconomic trends.

The Big Trade-Off

The trade-off I am highlighting in this piece is the one between current consumption and productive investment. This happens in two ways: First, as previously suggested, increased unproductive government spending is financed in no small part by debt, much of which is bought with private savings. The private savings used to fund this government spending most likely would have found a more productive use otherwise. This is how government spending, via the debt financing channel, crowds out private investment.

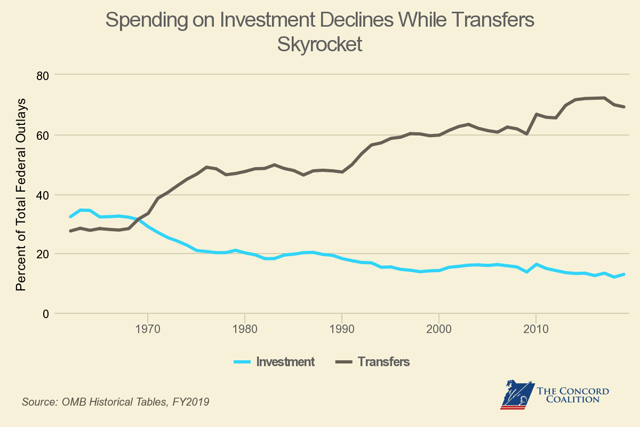

Second, as I explained in The Monetary Death Spiral Stubbornly Persists, excessive unproductive government spending also crowds out the government's own investment spending. We can see this by comparing all the various transfer payments to investment spending as a share of the federal budget over time:

Source: Concord Coalition

Since the late 1960s, government investment in such purposes as education & training, research & development, and major physical capital like infrastructure has shrunk as a percentage of total spending, while transfers (current consumption) have risen.

It's important to note that it doesn't make a difference to GDP whether this spending was debt-funded or not. There are two reasons this is the case: First, because, as the name would suggest, transfer payments simply transfer the capacity to consume from one group to another.

Second, because consumption spending has increased so much over the decades, it would be nearly impossible for investment spending to keep up. There simply aren't that many productive investments for government dollars to fund.

This is how, when government spending is literally one of the components of GDP, an increase in government spending on something economically unproductive can actually result in flat or even decreased GDP. It takes money away from investment and gives it to consumption, a more fleeting and fickle component of GDP. Or it takes money away from some consumers, via taxation, in order to fund other consumers — with some leakage in the process due to bureaucratic expenses.

Unlike investment, consumption cannot, on its own, make the economy more efficient, productive, or innovative and thus cannot produce more economic growth or a higher standard of living. Only investment can do that. And when investment dollars are being pillaged in order to fund consumption, economic output inevitably suffers.

Conclusion

The next time you hear economic pundits bemoaning the lack of additional trillions spent by the federal government (yet) for pandemic relief, remember this trade-off. If more stimulus money is passed by Congress and signed into law, it will almost certainly come at the cost of lower economic growth in the future. This is because money spent by the government on current consumption today will inevitably come from a combination of taxpayer income/wealth and private savings.

The $4 trillion dollars that have been spent this year (above and beyond the original 2020 federal budget) will already depress growth over the long-term and exacerbate the Monetary Death Spiral, even if that spending has prevented immediate economic damage. And, of course, the CBO's projections for continual $1 trillion+ fiscal deficits for the remainder of the decade do not even consider the coming exhaustions of major federal trust funds, which will almost certainly result in further tax- or debt-funded government spending. (More drag on growth.)

As I've explained to subscribers of High Yield Landlord, I believe one of the best places for investors to hide out in the coming decades will be publicly listed real asset companies that own real estate, natural gas midstream assets, infrastructure, farmland, and renewable energy assets.

As weak growth, low inflation, and near-zero interest rates persist, the generous and stable cash flows from real assets will become increasingly attractive for all kinds of investors.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario