Crackdowns in places like Inner Mongolia are easier to understand when you understand the difference between threats to the state and threats to the regime.

By: Phillip Orchard

In July, Chinese authorities announced a three-year plan to phase out Mongolian-language instruction for grade schoolers in the nominally autonomous northern region of Inner Mongolia. Beijing had imposed similar changes on ethnic Uighurs and Tibetans in 2017 and 2018 as part of its draconian forced assimilation campaigns.

As a result, many of the 6 million or so ethnic Mongolians living in the province were understandably unnerved, seeing the move not as a well-intentioned policy aimed at promoting national unity and development, but rather as a form of cultural genocide – and a precursor of worse to come.

When the fall school term began on Monday, and students cracked open their new state-compiled textbooks to find them written in Mandarin, the result was what qualifies as all hell breaking loose in stability-obsessed modern China. Tens of thousands of people reportedly took to the streets throughout the province. Students and teachers walked out of schools – or, more accurately in some cases, climbed and pushed their way out after authorities tried to lock them in.

Videos posted on social media appeared to show several scuffles with police. Beijing responded Thursday by doubling down on its new policies and launching a fresh campaign to arrest troublemakers.

Dominating buffer zones such as Inner Mongolia is a core Chinese geopolitical imperative. It’s why the Communist Party of China is reportedly expanding its mass internment of ethnic Uighurs in Xinjiang, tightening the screws in Tibet, dismantling “one country, two systems” in Hong Kong, sparking royal rumbles in the Himalayas and putting the squeeze on Taiwan.

These moves, however, are only intensifying international pressure on Beijing at a time when it’s still grappling with the epochal political and economic crises created by the pandemic. So it would seem self-defeating to open up yet another front of unrest in the comparably stable Inner Mongolia. But Beijing doesn’t think it can manage these crises in any other way.

Around the Core

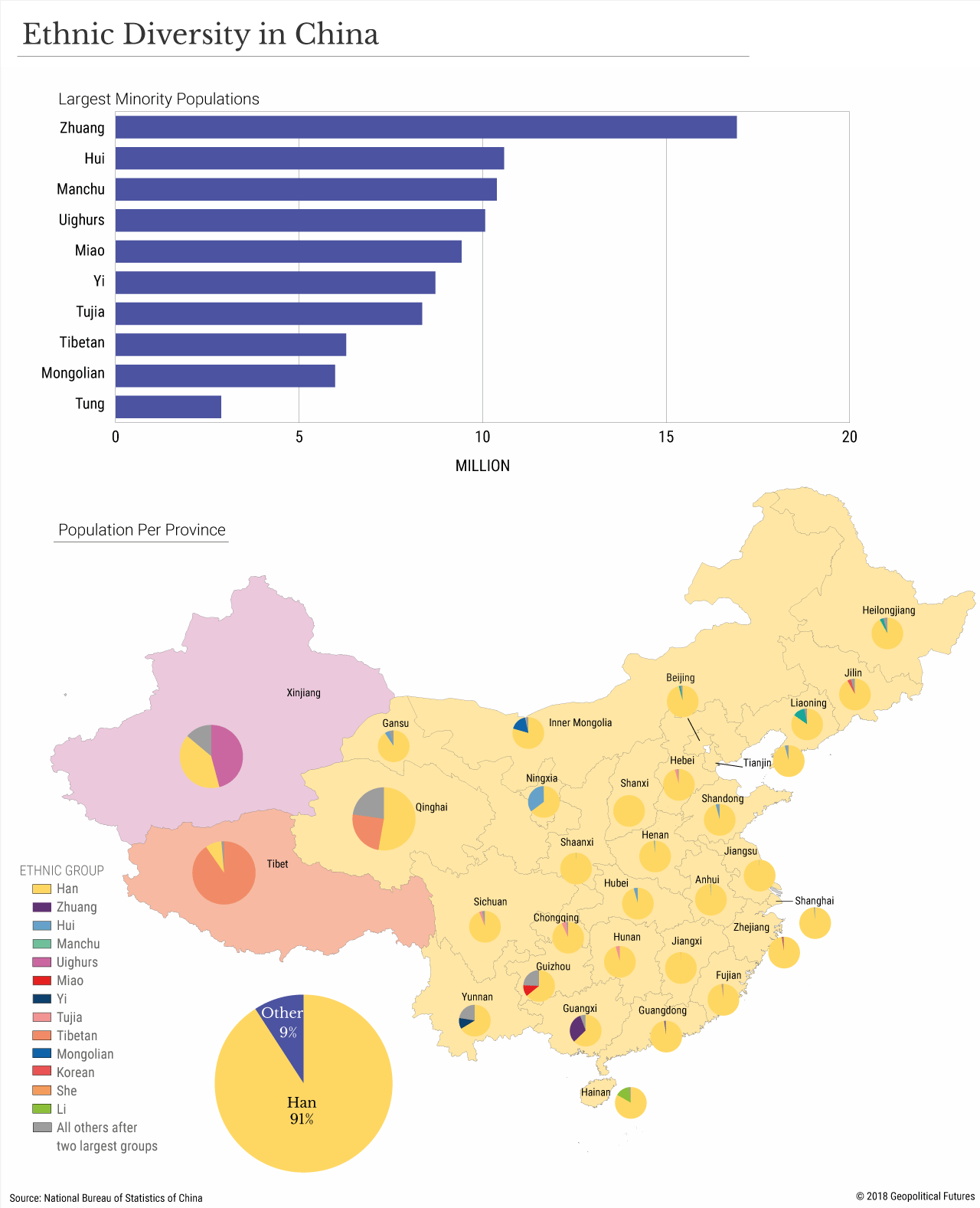

Five subordinate regions surround the ethnic Han core in China: Tibet, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, Manchuria and Yunnan. The regions are defined by impassable mountains, unforgiving jungle, vast desert grasslands and high tundra.

When the core has been united under central rule, these features have served as shields against outsiders, their inhospitable geography giving China as a whole the defensible borders and security the Han core alone lacks.

Between the Himalayas and the jungle uplands bordering Indochina, for example, southern China is protected and isolated by a true Great Wall. The west is a vast and dry expanse that would stretch thin any invading force. The North is the Gobi Desert and Siberia, bereft of major population centers.

The core is exposed to overland invasion only through a pair of narrow corridors closer to the coasts, through parts of Manchuria and across the Vietnam border, allowing China to concentrate its defenses. Otherwise, China can’t easily invade anyone over land, but nor can it be invaded.

Historically, however, when central authority over China’s buffer regions weakens, bad things tend to happen to China. Their geographies made them ethnically, culturally and economically distinct from the Han core, to varying degrees, and thus often outright hostile to the Han encroachment.

And whenever the core has succumbed to its internal pressures, devolving into regionalism, warlordism and disarray, the outlying buffer regions have been quick to go their own way. If occupied by or aligned with an outside power – e.g. the Genghis and Kublai Khan’s Mongol invasion from north of the Gobi, the Manchu in the 1600s, the Europeans in the 19th century, the Japanese and Russians a century ago – the Han core fractures, and dynasties fall.

So even before the CPC had put the finishing touches on its victory in the Chinese civil war in 1949, it began turning its attention to the buffers, waging a decadelong campaign to subjugate Tibet, Yunnan and Xinjiang (to say nothing of expelling foreign forces from Manchuria). And the modern CPC, particularly under Xi Jinping, routinely cites China's historical pattern as justification for its crackdowns on the outlying ethnic regions.

The party works diligently to keep the “century of humiliation” – the period between the 1830s and 1949 when the collapse of central authority in China led to it being carved up by foreign powers – in the collective Chinese consciousness. It must be neither forgotten nor repeated, or so the propaganda narrative goes, and the party will not cede to international interference in its efforts to fulfill its mandate of national rejuvenation.

It’s easy to dismiss Beijing’s historical justification for dominating the buffers as anachronistic. In theory, there are ways an outside power could use the buffers to threaten the Han core. India, for example, could try to dominate the Tibetan plateau and take control over China’s water supplies.

But in reality, the days of overland invasion in China are gone, to say nothing of foreign occupation. No outside power is strong enough to overcome both the geographic barriers and the firepower China is now able to position along its borders, even if one wanted to.

And there is no threat emanating from within the buffers themselves on par with the Mongols or the Manchu of past dynasties capable of supplanting the central government. The CPC has proved capable of enforcing its writ in the most remote, geographically fractured parts of the country with brute force and a willingness to adopt draconian practices like the “re-education” centers in Xinjiang.

It’s also relied heavily on more subtle and insidious measures, such as encouraging mass Han migration into the buffer regions, coopting ethnic institutions and civil society organizations like Tibetan monasteries, more tightly controlling school curricula, implementing a vast surveillance apparatus, and, of course, steadily narrowing the space for use of things like native tongues that can form the basis of a distinct identity.

Winning hearts and minds has been a comparably lesser priority, but Beijing’s massive infrastructure buildouts have helped integrate the outlying regions into the economy of the heartland and create at least some incentives to buy into the CPC’s plans for national prosperity

As a result, China’s buffers today are largely subjugated. The only real threat to the core from the periphery is Islamic terrorism. But beyond a pair of high-profile attacks – one at the gates of Tiananmen in 2013 and one in 2014 – even that has remained relatively contained to Xinjiang. A wave of self-immolations by Tibetan monks from 2009 to 2017 appears to have petered out.

Inner Mongolia, in particular, has been a relative success story in ethnic integration. Occasional clashes between ethnic groups and the state mostly died out decades ago. There is lingering discontent over the forced resettlement of hundreds of thousands of nomads, and occasional protests over environmental damage done by the state’s development initiatives, particularly mining, in the resource-rich region (where ethnic Han, which now make up more than 80 percent of the population, have enjoyed the lion’s share of the extraction spoils). But there’s no substantive secessionist movement, and signs that unrest is boiling beneath the surface are rare.

Beware the Buffers

China understands that its biggest potential threats today come not from the buffers but from outside powers uniting against it. And while there’s been more bark than bite from other countries in response to Chinese oppression, the party’s human rights record makes it easier for foreign leaders to rally public support for the painful measures required to truly challenge China.

They also make it more difficult for foreign businesses – ones China needs for employment, technology and diplomatic leverage – to stay in China. (See: persistent calls to boycott Western retailers that source materials allegedly produced by forced Uighur labor.)

So why does Beijing still fear the buffers – particularly one as sparsely populated and relatively placid as Inner Mongolia – so much that it would risk the backlash? The answer lies in the distinction between the interests of China as a whole and those of the CPC.

The CPC is not the 19th century Qing dynasty. The center is strong both in the core and the periphery. But while China is realistically safe from foreign invasion, it cannot fully shield itself from foreign influences. Combined with China’s immense internal pressure, these make the CPC’s hold on power inherently fragile. The party therefore has a low tolerance for any threat to social stability, even relatively minor ones.

Even a pair of unsophisticated attacks by Uighur militants – which Beijing suspected were getting ideological and material support from militants in Central Asia and beyond – was enough to spook Beijing into effectively putting an entire region on lockdown. The fear of the public losing faith in its ability to provide security, and its fear of militants derailing Belt and Road Initiative projects (which are also essential to maintaining economic stability in the core) through Xinjiang to Central Asia, was evidently too overwhelming.

Similarly, its fear of civil society or religious institutions being used to mobilize the public against it partially explains its desire to control Tibetan Buddhism. One of Beijing’s core fears with Hong Kong protesters, meanwhile, is the ways they could – perhaps with Western assistance – stoke instability on the mainland by funneling money and media to dissidents, airing the party’s dirty laundry, or shielding enemies of the state.

Beijing is expecting foreign pressure to intensify over the coming decades regardless of how it chooses to govern its periphery. Put plainly, in the face of mounting pressures, the party’s foremost priority is control. Undermining ethnolinguistic diversity – eroding ethnic identity as something that can supersede loyalty to the CPC – has proved to be a ruthlessly effective way to deepen its control. So too has starting the nation’s citizens on a steady drip of ideology and propaganda from a very young age.

The CPC is also betting that, at the end of the day, outside powers won’t really care all that much about human rights – at least not more than they care about strong economic or diplomatic ties with Beijing – and that its policies will succeed in the buffer zones.

And it may be right. What it’s allegedly doing in Xinjiang is horrifying. And yet, there’s been barely a whiff of meaningful outrage from governments from Muslim-majority countries such as Turkey, Pakistan and Indonesia.

To the extent that there has been backlash over Xinjiang, it’s mostly come in the form of Western sanctions – mainly targeting Chinese sectors like AI and other emerging technologies, which the U.S. and friends are keen to check for geostrategic, not human rights, reasons.

Matters as esoteric and plausibly well-intentioned as national curriculum standards in Inner Mongolia are hardly going to cause much of a stir abroad.

Either way, the central government seems to have concluded that pressure will eventually fade if its control is absolute. Internal movements lose support and wither. Foreign governments get distracted and move on.

Shareholders in foreign firms return focus to the bottom line. The CPC, in its mind, just has to hold on tight until they inevitably do – and hope that it doesn’t suffocate the nation in the process.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario