By Reshma Kapadia

Illustration by Justin Metz

Ed Daizovi, a 57-year-old career diplomat, entered the retirement homestretch earlier this year: He had just moved back from Africa and was setting up a new home in Miami where he planned to retire next year with his wife of 29 years, after investing diligently to fund a comfortable retirement.

But the coronavirus pandemic—and the volatility stirred first by the market’s crash and quick recovery, and now by uncertainty heading into the election—is making Daizovi wary about his retirement timeline.

“If the market tumbles 30% to 50% by the time I’m ready to retire next year, I’m looking at one more tour in the foreign service,” Daizovi says. That’s far from ideal, as it would mean having to live apart from his wife as she settles into their retirement home.

For near-retirees, the Covid-19 recession marks the second major setback in little more than a decade—and this one strikes as many are hitting peak earnings and savings years. Now, they find themselves grappling with ways to preserve their retirement security—with fewer years to bounce back.

“Preretirees are getting the wind kicked out of them,” says Ken Dychtwald, head of consultancy Age Wave, of the challenges and confusion that those five to 10 years from retirement are facing. “Their portfolios are taking a hit. They can’t work longer with [high] unemployment. Their mom is sick, and their kids are moving back home.”

Among the near-retiree set of 50- to 64-year-olds, confidence about having enough saved for retirement has fallen to 48% from 65% before the pandemic, according to a poll by Edward Jones/Age Wave released in August. And among those in this group with adult children, 28% have provided them with financial support during the pandemic, exacerbating savings shortfalls.

These concerns come at a time when some families’ budgets are already strained by a variety of factors, such as job losses, income cuts, or efforts to keep small businesses afloat. Almost a third of small-business owners and 8% of baby boomers said their household income had fallen by half or more during the pandemic, according to a financial-wellness survey from Prudential Financial, Prudential Financial Inc. released in July.

On top of those immediate issues, the pandemic is stirring uncertainty around a number of other key concerns in retirement, including taxes and pensions, as governments reassess budgets and spending priorities. Investors should also reassess what their savings could generate in long-term market returns as global economic growth takes a hit and interest rates are at historical lows in much of the world.

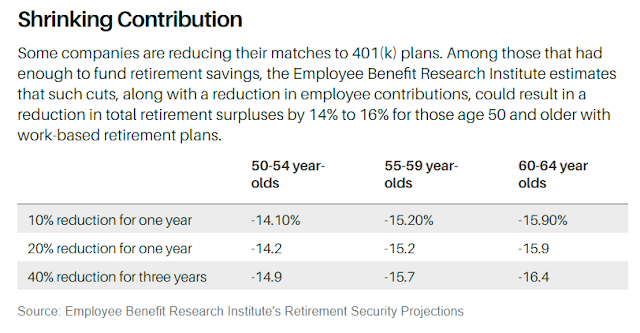

The pandemic also has had an impact on many near-retirees who are still employed. Roughly 15% of employers have either suspended or cut matching contributions to 401(k)s, with an additional 10% considering doing so, according to a survey of 543 employers by Willis Towers Watson.

And that can have an impact on overall retirement security. Among those with enough savings to fund their retirement needs, a 10% reduction in employer matches for a year along with a 10% reduction by employees in plans where the match is suspended cuts roughly 14% off the total surplus for 50- to 54-year-old workers, according to projections by the Employee Benefit Research Institute.

On an individual level, there are ways to mitigate the Covid-19 hit—and not all have to be drastic. Barron’s canvassed financial planners and retirement experts to see what adjustments near-retirees can make to bridge a difficult period without derailing retirement plans.

RESIST RETIRING PREMATURELY

Given the health risks created by the pandemic and uncertain outlook for certain industries, early retirement may seem like an attractive option. But advisors recommend that those who are five to 10 years away from retirement should stay in the workforce, if possible.

“The best way to improve retirement financial outcomes is to work longer,” says Jamie Hopkins, director of retirement research at Carson Group. “A year or two before retirement, we see people tighten their belts and reduce spending, but that has minimal impact versus working six months to a year longer.” Indeed, 34% of 50- to 64-year-olds in the Edward Jones/Age Wave survey said that Covid-19 has changed their retirement timeline.

Of course, working longer is easier said than done—even more so now with a spike in unemployment. While older workers typically have substantially lower unemployment rates than those 25 to 54 years old—roughly 15% to 20% over the past decade—that hasn’t been the case through this pandemic, says Richard Johnson, director at Urban Institute’s Program on Retirement Policy. As of July, the overall unemployment rate for those ages 55 to 64 sits at 8.7%, just 5% lower than that for younger cohorts.

That’s a troubling trend, as it has also taken longer for older workers to get rehired out of past downturns, with those 62 and older who lost their jobs only half as likely to be re-employed as people in their 30s and 40s, Johnson says.

Advisors recommend taking a closer look at retirement savings, deferred compensation, and stock options to see if other paths to employment are feasible—including a job that pays benefits but doesn’t necessarily provide the same level of income, or turning a furlough into a phased retirement where workers transition in steps from full-time work to full-time retirement. Workers could tap savings to set up a consulting business, hire a career coach, or get more training to pivot into a different career.

Being realistic about the changes the pandemic has brought to various industries—and how long it could take to get back to a level of normalcy—is also important. “Some clients hold out for an equivalent offer and spend so much time out of the workforce they end up with a two-year gap,” says Jeffrey Levine, director of advanced planning at Buckingham Wealth Partners.

“Then they are even older, and it becomes even harder to get back in the workforce.”

FREEING UP CASH

Finding a job could take time, and even those who have emergency savings may be running low nearly six months into the crisis. Yet the sharp stock market rebound from the March depths and historically low interest rates offer an opportunity to replenish and expand cash cushions.

Advisors recommend anywhere from 18 months to three years of expenses in liquid assets, depending on circumstances. For those who have gotten an early-retirement package or severance, Katherine Liola, founder of Concentric Private Wealth, suggests keeping much of it liquid to generate an income stream, since it could take some time to secure another job.

For small-business owners near retirement, having a cash pile is paramount, given the pandemic’s impact on many companies’ revenue and sale valuations. Some advisors recommend that business owners have two years of cash on hand to keep operations going until conditions return to more normal levels, enabling them to possibly sell the business. That might mean cutting expenses, negotiating with vendors, or tapping credit lines as well as any available pandemic aid.

“We don’t know what the recovery path looks like or the speed at which it could happen,” says Brandt Kuhn, managing director at Beacon Pointe Advisors. “If you qualify for [government relief] programs, take the opportunity and make your runway as long as possible.”

When it comes to freeing up cash, the pandemic has upended some of the traditional rules—like not taking on debt on the eve of retirement. With interest rates at record lows and housing prices holding up, some advisors recommend that near-retirees look to their homes as a possible source of cash.

If the rate on their mortgage is a percentage point or more than the current rate, refinancing could make sense. “Would you rather sell equities in a portfolio that you expect to earn 6% to 7% or borrow from a home at 3% to 4%? Use the asset with the lowest return in the portfolio, which is home equity,” Hopkins says.

Another option: opening a home-equity line of credit that can be drawn on in increments if markets take a turn for the worse. The idea is to tap the line of credit and pay it back when markets recover.

The next best place to free up cash is through investment accounts, taking into consideration taxes and asset types for a guide on what to tap first. Here, too, the pandemic has made it acceptable, if not ideal, to break some long-held guidelines, such as not raiding a 401(k).

Policy makers have made it easier for those affected by the pandemic to do just that—and advisors say those who need to bridge an income gap should take advantage of the changes. The Cares Act allowed those affected by the pandemic to tap up to $100,000 in retirement assets this year without getting hit with the 10% penalty if they are under 59½, and the act also made it easier to take out a loan of up to that same amount that can be paid back over a period of five years

Of the two options, advisors slightly favor the loan because, behaviorally, it increases the chances that the money will be replenished. If the loan is paid back in five years, there is no tax hit. And for those who opt to take distributions of up to $100,000 from their 401(k) or individual retirement account this year, taxes will be spread out over three years. But for those who manage to repay the distribution within three years, a tax credit is applied, essentially making it akin to a tax-free loan.

The determination of whether someone wants to take a loan or distribution has to be decided up front, with loans required to be paid back on a specific schedule.

Tax considerations also support use of retirement assets for those who have lost their job or had their income reduced. Savers who find themselves in a lower tax bracket could minimize taxes paid on a withdrawal from a 401(k) or individual retirement account—something that could become even more important when the Cares Act provisions are no longer in effect.

However, if someone has already made substantial income this year, Carolyn McClanahan, founder of Life Planning Partners, says that it may be better to draw from taxable accounts where the 15% tax on capital gains may be a less costly way to free up cash than paying income tax on retirement assets. What’s more, with stocks in certain sectors still down after the crash, an investor might be able to sell at a loss and take a tax deduction.

Which assets to sell first? Given the market’s rise, advisors recommend taking profits in stock portfolios with the most-aggressive profiles, or rebalancing to rebuild cash cushions, if possible.

Here’s one rule that has stayed largely the same: If you are in good health, try to wait to claim Social Security as long as possible. The roughly 8% increase in benefits each year a worker delays claiming through age 70 is difficult to match elsewhere. Plus, the payout is for life—so the bigger it is, the better—and tapping it early can have ripple effects for the surviving spouse.

RETHINKING RISK

The pandemic is the type of event that calls for introspection—and that holds for finances, as well, with advisors encouraging clients to re-examine their risk tolerance and long-term return projections. Near-retirees should also use this time to consider how they want to be cared for as they age, and their expectations about pensions and taxes.

Indeed, nearly a quarter of older Americans said the crisis had caused them to reduce their risk tolerance for the long term, according to a June survey of 56- to 75-year-olds with at least $100,000 in investible assets by the Alliance for Lifetime Income, a group focused on educating the public about annuities and promoting them as a tool for retirement income.

One place to start a reassessment is with a look at asset allocation. For near-retirees who have lost jobs or are worried about layoffs, McClanahan has been encouraging them to shift closer to a 50/50 stock and bond portfolio, taking advantage of recent market gains to rebalance. For those under 59½ who may need to rely on nonretirement assets next year, McClanahan recommends an even more conservative allocation in the taxable brokerage account, if it needs to be used as a bridge after this year’s Cares Act provisions expire.

The unprecedented amount of stimulus pumped into the global economy also means that investors should take a closer look at the safer, fixed-income part of the portfolio, as some bond funds have suffered double-digit losses.

Some advisors favor bond ladders once clients are beginning to tap portfolios, rather than bond funds, to minimize volatility, especially as many funds have veered into riskier assets to generate returns. The premise is simple: buy bonds that mature in different increments with the intent of holding them to maturity, collect interest income along the way, and replenish with new bonds as old ones roll off.

Other advisors, like Jason Fertitta, head of registered investment advisor Americana Partners, are wary of exchange-traded bond funds whose sharp losses could precipitate selling from investors, exacerbating possible pain for investors. “Of all the asset classes, fixed income is the one you need to be most careful in,” he says.

Given all the easy money being pumped into the global economy, Fertitta says he has turned more defensive and sees a case for a longer-term inflation hedge by increasing clients’ exposure to real assets like real estate to 10%-15% from 3%-5%. “My biggest concern is that the levers the Federal Reserve is having to pull to keep this market going is very experimental, and we don’t know when inflation is coming,” he adds. “We have to put in some assets that could benefit from inflation. Real assets historically were a small part of the portfolio, and we are certainly open to that being a larger piece.”

Near-retirees are also rethinking another risk: their long-term care plans, with the Edward Jones/Age Wave poll showing that the pandemic prompted almost 30 million Americans to have end-of-life discussions for the first time.

The pandemic’s toll on nursing homes and other congregate-care facilities has further increased near-retirees’ preferences to add at-home care to their retirement planning, Hopkins says. Such care isn’t cheap: A home health aide can range from $150 to over $350 a day, with Genworth Financial estimating $50,000 a year for a home health aide working a 44-hour week, and rising to an average $150,000 for full-time care.

The trillions of dollars being spent to help the economy out of this recession means that investors should also reassess expectations for pensions and taxes. Many state and local governments were already struggling financially, but the crisis has exacerbated the situation, and pension funding levels are forecast to take another hit, says Olivia Mitchell, executive director of the Pension Research Council and a professor at University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business. Among the most precarious are states such as Connecticut, with a funding level of just 28%, and Illinois, at 20%.

The fallout will take time—and a lot depends on Congress and what it does to deal with local governments’ fiscal distress. As of now, many states have constitutional provisions that require pensions to be paid in full, but Mitchell notes that the bankruptcies of Puerto Rico and cities like Detroit brought pension cuts—a 4.5% haircut in Puerto Rico and the elimination of the cost-of-living adjustment in Detroit’s case. Congress would have to change laws for states to declare bankruptcy.

Still, the potential hit to pensions is enough for planners like Jody D’Agostini at Equitable Advisors to be cautious. She bakes in a reduction in expected pension payments for clients, and takes a conservative approach to Social Security that factors in no cost-of-living adjustment and a 20% to 25% reduction in benefits for wealthier clients who could be the first to see a reduction.

Then there are taxes. At some point, the bill is also going to come due for the trillions being spent to help the U.S. economy. “If taxes have to double because of the fiscal hole we are in, that does tend to threaten people’s planning,” Mitchell says.

The November election could offer some clarity, but for now, advisors are stressing diversification, including adding to Roth IRA accounts if possible, as well as tax-efficient investments like municipal bonds. As the postpandemic world becomes clearer, the name of the game for near-retirees will continue to be flexibility.

For the diplomat Daizovi, the stock market rebound has provided an opening to sell some of his positions and build a bigger cash buffer, so he can follow through with his original retirement plan—and still have some money to buy stocks when the market dips. “This situation has given me a reason to take a hard look and come up with a plan B,” he says.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario