Companies like the Wagner Group fill in certain security blanks

By: Ridvan Bari Urcosta

Belarusian intelligence has accused Russia of sending private citizens to interfere in the country’s affairs and generally engage in acts of provocation. These same citizens participated in the annexation of Crimea a few years ago and fought on Russia’s behalf in the breakaway region of Donbass, according to officials in Ukraine, who demanded their immediate extradition to Kyiv. Instead, the Belarusian government sent them back to Russia.

To no one’s surprise, the citizens were members of the infamous private military company known as the Wagner Group, which over the past few years has been involved in every international conflict strategically important to Russian interests. The case of Belarus and Ukraine – the first instance on record of Wagner operating so close to NATO’s eastern flank – underscores just how useful a political tool Wagner has become for the Kremlin.

Organization and Formalization

Private military companies are by no means unique to Russia, but Wagner has a unique Russian flavor. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the concomitant depression left thousands of Russian soldiers rudderless.

They were unemployed but well trained and ready to fight, so they informally banned together in the 1990s to sell their services throughout Eurasia. By 2008, there were no fewer than a dozen private military companies in Russia. The most famous of them, the one that would serve as the blueprint for Wagner, was officially created in 2013 in response to the Syrian civil war.

Known as the Slavonic Corps, the group comprised former Russian special forces whose primary task was to protect the oil fields near Deir el-Zour. This naturally led to clashes with the Islamic State.

Among the members of the Slavonic Corps was Dmitry Utkin, a former special forces commander in the GRU, Russia's military intelligence unit, more commonly referred to by his call sign, “Wagner.”

Most would be arrested for mercenary activities when they came back to Russia. (The legal status of private military companies is murky. Officially they are illegal, but they are “coincidentally” deployed to areas vital to Russian interests. One of the Wagner Group’s biggest benefactors, a billionaire named Yevgeny Prigozhin with oil and mining operations in Africa and the Middle East, is tight with Russian President Vladimir Putin.)

Either way, the Wagner Group returned to Syria in 2016 and cooperated closer with Russian regular forces. They are believed to have participated in the assaults on Palmyra in 2016 and 2017, and they are rumored to have fought with Syrian forces, and thus against U.S. forces, in the battle of Khasham in 2018.

The group has since expanded its reach considerably, particularly in Africa. It trains the military in Sudan, which reportedly granted mining concession agreements to a company tied to Prigozhin. It has participated in military parades in the Central African Republic, and is thought to be in Burundi as well. Its most high-profile client, of course, is Libya.

The United Nations estimates that more than 1,000 Wagner members are fighting alongside the Libyan National Army, led by Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar. The document says that mercenaries help to repair military equipment and also perform the functions of gunners, sappers and specialists in electronic warfare.

Putin denies funding or supporting them; in fact, he has said explicitly that they do not represent the Russian government in any way. But curiously, Haftar met directly with Putin and Prigozhin back in 2018, and by 2019, the group was reportedly assisting in Haftar’s attempt to retake Trípoli.

Leverage and Maneuverability

This partly illustrates the allure of Russia’s private military companies: plausible deniability. They simply don’t have the political baggage of total state affiliation, which gives Moscow political leverage and maneuverability.

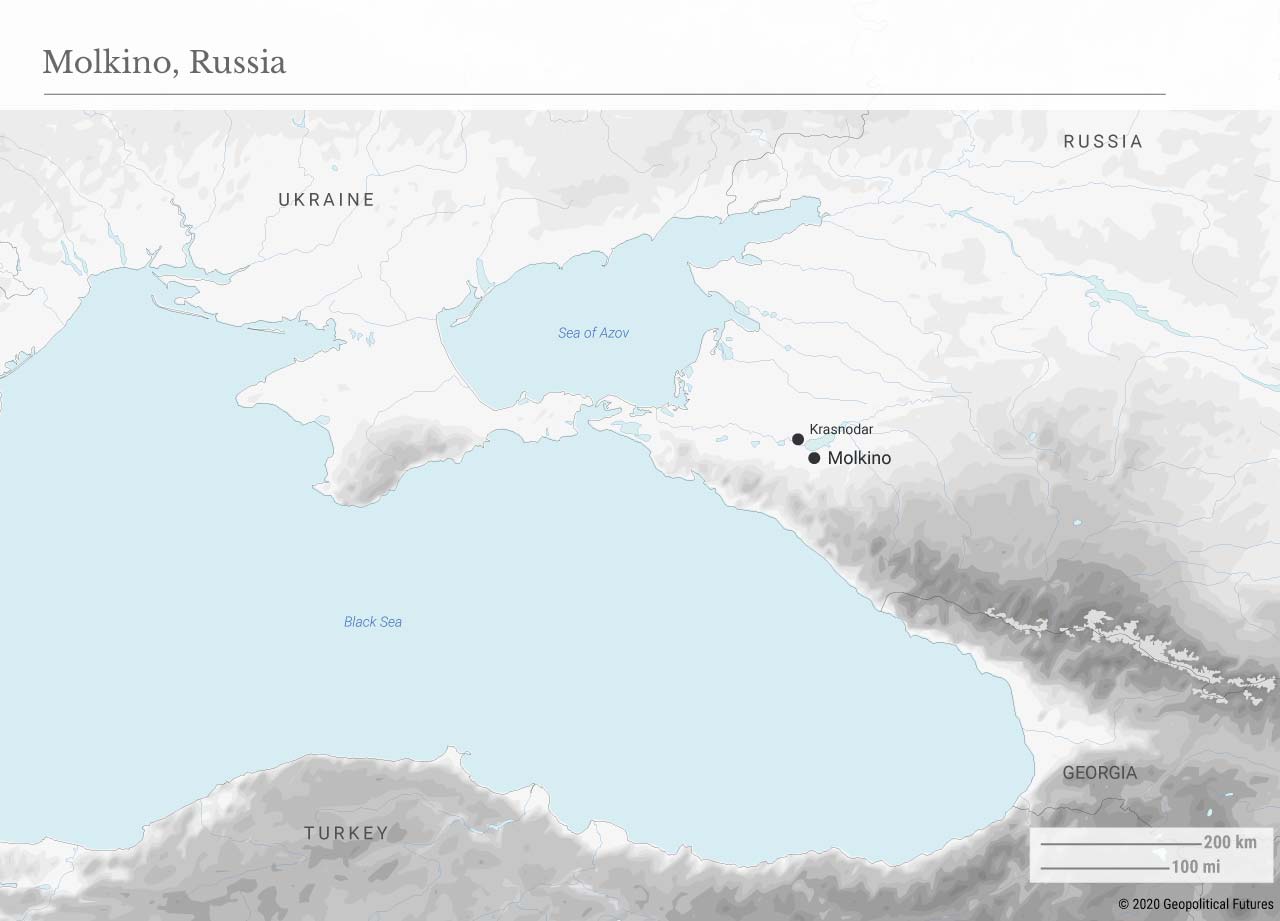

They are well trained, they have their own equipment and training facilities – the primary one located in Molkino in Krasnodar Krai near the Black Sea – and even have their own airfield. Yet, they are also relatively cheap on the global market. Salaries for the average soldier start at $2,000 per month but can go as high as $20,000 per month.

The low end of that spectrum may seem low, but it’s higher than enlisted pay in the Russian armed services. (It should be noted that reports from 2017 suggested salaries had dropped.) Money comes from private sources, local governments that want to use their services and, allegedly, classified disbursements from the Ministry of Defense.

So even though Moscow can claim not to use private military companies, it makes sense that it would. Groups like Wagner can secure facilities conventional militaries can’t or won’t for political purposes, and thus they are perfect for non-linear and limited-scale conflicts. (They tend to fare worse against conventional militaries.)

They usually work more closely with local security forces and help to organize those forces.

Moreover, military campaigns conducted between states can be complicated and logistically complex. Private companies can simplify this process. And ultimately they give Russia another contingent of forces to work with. When Putin announced plans to partially withdraw from Syria, Moscow thought it could offset the losses with private military companies.

Notably, Russia’s preference for private military companies is a relatively recent development, one ushered in by the conflicts in Syria and Ukraine, which made it clear to Moscow that the Wagner Group is an effective supplementary global tool. Maintaining semi-official groups enables the Kremlin to send them into dangerous places to secure Russian companies’ interests without officially claiming responsibility.

They fill out the strategic blanks, forming a sort of symbiosis between the state and the private groups whereby the state allows soldiers of fortune to earn money. In return, the state gets subordination and partial cover-up.

It’s a small but important part of the Russian grand strategy. Russia will continue to use the private military companies as an instrument of its global strategy in the near future especially under Putin’s rule.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario