Stabilizing its Arctic regions is becoming a priority for Moscow.

By: Ekaterina Zolotova

The fall of oil prices and the campaign to manage the coronavirus pandemic have taken a toll on Russian finances, perhaps nowhere more so than in the regions of the Arctic. In the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous District and the Komi Republic alone, regional revenue fell by 60 percent compared with last year.

The Krasnoyarsk Territory and Murmansk Region were also significantly affected. And while this is a sign of hard times to come for the people who live there, these oft-overlooked regions, which are among the biggest oil and natural gas producers for a national economy that relies heavily on oil and natural gas, also affect the financial stability of the country writ large.

The Kremlin understands as much and, if push comes to shove, will make it a priority to maintain the economic health of the Arctic regions. But given its budgetary shortfalls, it will struggle to do so.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, the Russia it left behind was a much more “northern” country. It lost the fertile lands of Ukraine and Central Asia, and there was only so far it could expand south into the newly formed countries beneath it. And so the Arctic, which constitutes about 20 percent of Russian territory, has become a space in which Moscow can gain leverage and military and economic power.

Indeed, the region is considered by many to be essential to Russia’s becoming a great power again. For centuries, the Arctic was a liability, a natural border that hindered Russian expansion.

Now, as climate change melts the ice and as technological development creates more opportunity, it’s an asset, one that can someday be a hub for trade and military activity. More important to Moscow, it’s a resource to mine.

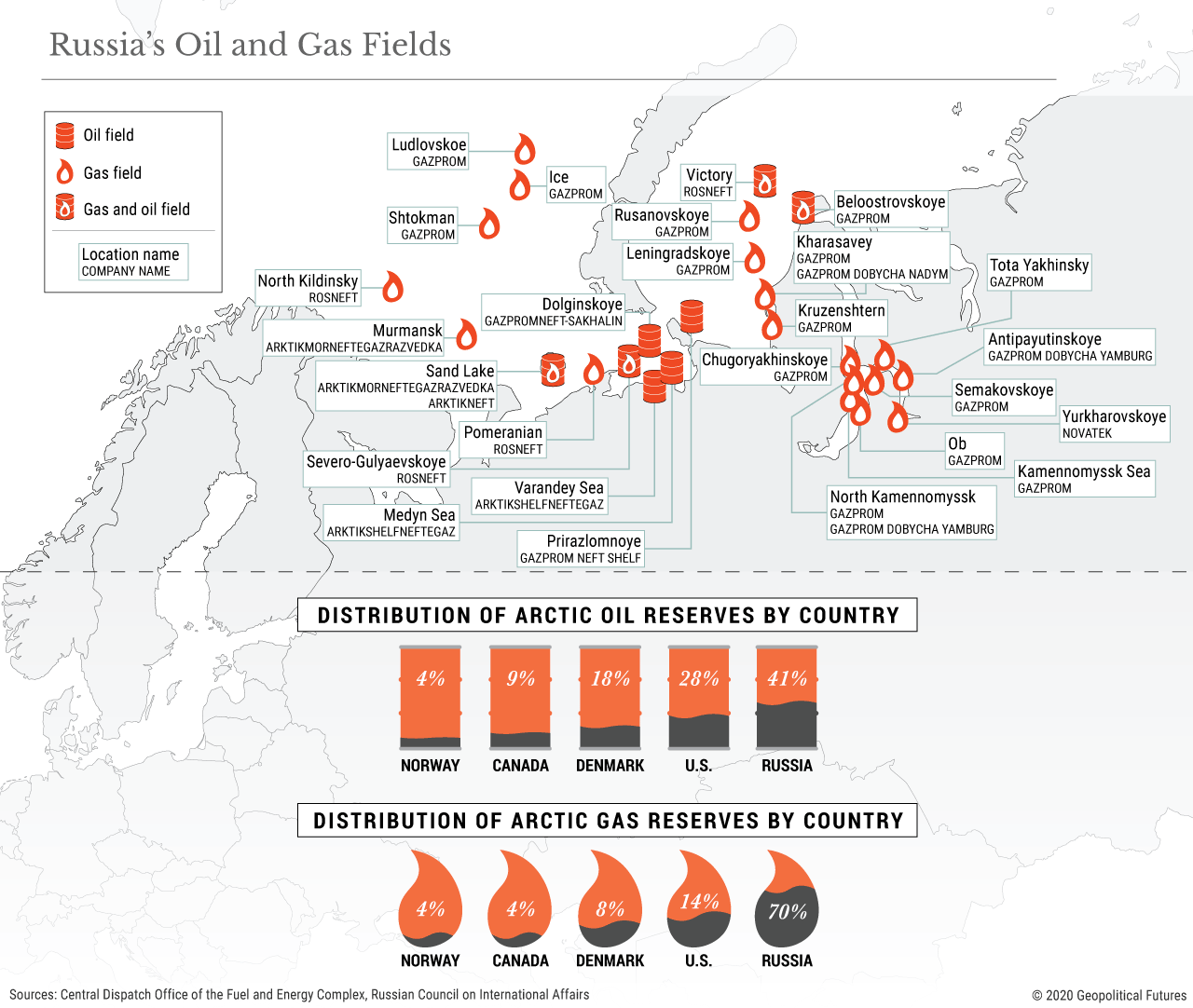

About 41 percent of all the Arctic’s oil and gas resources are located in Russian territory. More than 80 percent of Russia’s gas and about 17 percent of its oil is produced here, accounting for about 10 percent of the country’s gross domestic product and about 25 percent of Russia’s exports, and contributing some 15 percent to the government budget. (The Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous District itself accounts for about 43.5 percent of the total resources of the Arctic.) The region is also a potential source of rare earth elements.

The promise of the Arctic has naturally attracted other countries that are now in direct competition with Russia over its potential benefits, including Denmark, Canada, Norway, Iceland, Sweden and the United States.

Even countries that don’t directly border the Arctic – especially those in the Asia-Pacific – are showing interest, since the proposed North Sea trade route would significantly reduce the delivery time between Asia and Europe.

To get a leg up on the competition, Russia needs a strong military, economic and commercial foundation. To that end, it has been expanding its military bases and its Arctic Fleet and has slowly begun to construct viable ports for the long term.

Year-round, in particular winter, navigation cannot be carried out without a fleet of powerful atomic icebreakers, which need ports and other infrastructure. The government in Moscow knows that if it ever wants to establish such a fleet, it needs to start now.

Which is why the Kremlin wants to strengthen the region’s economy by attracting investments and qualified personnel, and by building infrastructure. Oil extraction, and therefore the expansion of Russian influence, requires a constant influx of skilled labor, modern technologies and infrastructure and, of course, the support of the local population.

The collapse of the Soviet system had a huge impact on the development of the Arctic – production in Yakutia-Sakha and Chukotka decreased, some mining centers and industrial settlements were completely abandoned, poverty and unemployment rose, and the reduction in northern benefits accelerated the outflow of the population from the region. Regions like Yamal-Nenets and even Murmansk lost about 20-25 percent of their population.

Moscow knows from the experience in the immediate aftermath of the Soviet Union’s collapse that without financial and tax incentives, it will be difficult to keep a skilled population, capable of supporting economic projects in regions with a climate as harsh as that in the Arctic.

In Soviet times, the government factored in the “cost of cold,” so sometimes wages in the Arctic were as much as four times higher than in other regions of the Soviet Union. This is why my grandparents moved from central Russia to Murmansk, and indeed, in the 1970s they could afford much more than people from Moscow. But even today, the region, which sports Russia’s highest per capita incomes, continues to attract labor.

It’s a good thing, too, because job vacancies in the region among resource extraction and industrial construction companies are growing. To stimulate labor inflows, the government has introduced the “northern allowance,” a bonus added on to wages. The size of the bonus depends on the region.

For example, in the Chukotka Autonomous District, employees receive a bonus of up to 100 percent of their salaries, whereas in Yamalo-Nenets the bonus is 80 percent.

This is why some northern regions like Yamalo-Nenets have the country’s highest level of family welfare. An average family with two children in Yamalo-Nenets in 2019 had almost 90,000 rubles ($1,300) left each month after covering the minimum expenses, compared to 55,000 rubles in Chukotka Autonomous District and 52,000 rubles in Nenets Autonomous District.

In the region of Moscow, by contrast, the same family would have had about 40,000 rubles left. Average monthly wages in Chukotka and Yamalo-Nenets are also higher than in Moscow and other regions – 109,300 rubles and 102,100 rubles, respectively, compared to 95,000 rubles in Moscow.

The government is trying to attract skilled workers in other sectors besides energy to come to the Arctic areas. For example, Moscow promised a one-time bonus of up to 3 million rubles for medical workers. In addition, the state is trying to attract investment and entrepreneurs by providing tax benefits and other tax advantages.

Support is provided for the construction of ports, such as a zero income tax rate for 10 years or zero value-added tax on services for sea transport of export goods and their icebreaking support.

Because of low oil prices, the OPEC+ production cut and the overall economic slowdown, exploration and mining are on the decline, and there’s less investment flowing into the region. If the situation leads to an erosion of salaries or social benefits, people may begin to gradually leave the region, just as they did in the 1990s.

But there are limits to how much financial aid Moscow can offer to prop up life in the Arctic, including for political reasons; already there is infighting within the Ministry of Finance, and there’s discontent in other regions, such as the Caucasus, due to insufficient funding. Even within the Arctic itself there is a rivalry between regions over funding.

To streamline its support policies and minimize dissatisfaction, the Kremlin has been considering optimizing the Arctic space and is striving to create an Arctic federal district. Yet this idea, too, sparked a backlash.

The region is very divided in terms of population and wealth, and different regions have different opinions on ideal economic strategies and ecological questions.

The indigenous population is dissatisfied with the activities of large Russian energy companies that often cause the destruction of their indigenous environment. Moreover, the ruling United Russia party is not strong in all the Arctic regions.

The Kremlin tried to merge the Arkhangelsk Region with the Nenets Autonomous District last month, during the height of the country’s coronavirus outbreak, but was forced to back down in the face of local protests.

The slump in oil prices and the broader economic downturn will damage Russia’s efforts to develop the Arctic. Without financial incentives and development, critical investment and specialists could even begin to move out of the region.

This could put Russia at a disadvantage in the international race for influence in the Arctic. The Kremlin will make significant efforts to prevent this outcome and keep up the pace of economic development in its Arctic regions.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario