Thwaites Glacier is melting at an alarming rate, triggering fears over rising sea levels

Leslie Hook on the Antarctic Peninsula, Steven Bernard and Ian Bott in London

Even by the standards of Antarctica, there are few places as remote and hostile as Thwaites Glacier.

More than 1,000 miles from the nearest research base, battered by storms that can last for weeks, with temperatures that hit -40C in winter, working on the glacier is sometimes compared to working on the moon.

Dubbed the “doomsday” glacier, Thwaites, perhaps more than any other place in the world, holds crucial clues about the future of the planet.

Only a handful of people had ever set foot on Thwaites before last year. Now it is the focus of a major research project, led by British and American teams, as scientists race to understand how the glacier — which is the size of Britain and melting very quickly — is changing, and what that means for how much sea levels rise during our lifetimes.

“It is the most vulnerable place in Antarctica,” says Rob Larter, a marine geophysicist and UK principal investigator for the Thwaites Glacier Project at the British Antarctic Survey. He takes a map and points to parts of the deteriorating glacier that have already broken off. “A lot of this is no longer there,” he says.

The scientists studying Thwaites go to extreme lengths to carry out their research. Geologist Joanne Johnson spent eight weeks sharing a tent with just one other person in the Thwaites area earlier this year.

“If something goes wrong, you are a very, very long way from help,” says Ms Johnson, a geologist at the British Antarctic Survey. Getting along with your colleague is crucial for survival. “Although you are in isolation, you are actually not very isolated at all, because you have this person who is with you 24 hours a day.”

The extreme version of lockdown, she says, was not too bad. “I really enjoy that kind of world, I enjoy the isolation, and feeling like you are at one with the landscape,” she says. But the situation of Thwaites Glacier is more alarming. “The glacier is changing so fast at present, that we are very concerned that it will drain a lot of ice into the sea,” says Ms Johnson. “It is quite unstable, and you can see that when you fly over it, with loads of crevassing.”

Ms Johnson is studying the rocks underneath the glacier, which will help to reveal its history. Knowing more about how Thwaites behaved in the past, she explains, should help scientists predict how it will respond to a warmer climate in the future. Her research is part of the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration, a £20m effort by British and American scientists that is one of the most ambitious Antarctic research projects ever undertaken.

But understanding the Thwaites Glacier is not just academic — it is crucial for predicting how sea level rises will impact on cities, and how we should prepare for a radically different world. If Thwaites continues to deteriorate, then by the end of the century the glacier could be responsible for centimetres or tens of centimetres of sea level rise.

“That doesn’t sound like much, but it is,” says David Vaughan, director of science at the British Antarctic Survey. “It is not about the sea coming up the beach slowly over 100 years — it is about one morning you wake up, and an area that has never been flooded in history is flooded.”

Melting ice threatens US

Antarctica holds around 90 per cent of the ice on the planet. It is equivalent to a continent the size of Europe, covered in a blanket of ice 2km thick. And as the planet heats up due to climate change, it doesn’t warm evenly everywhere: the polar regions warm much faster. It puts the icy continent of Antarctica and Greenland, the smaller Arctic region, right at the forefront of global warming. The South Pole has warmed at three times the global rate since 1989, according to a paper published last month.

As Antarctic ice melts and the glaciers slide toward the ocean, Thwaites has a central position, that governs how the other glaciers behave. Right now, Thwaites is like a stopper holding back a lot of the other glaciers in West Antarctica. But scientists are worried that could change.

“It is a keystone for the other glaciers around it in West Antarctica . . . If you remove it, other ice will potentially start draining into the ocean too,” says Paul Cutler, programme director for Antarctic glaciology at the National Science Foundation in the US.

Thwaites is getting thinner and smaller, losing ice at an accelerating rate. “The big question is how quickly it becomes unstable,” Mr Cutler adds. “It seems to be teetering at the edge.”

By itself, Thwaites could raise sea levels about 65cm as it melts. But if Thwaites goes, the knock-on effect across the western half of Antarctica would lead to between 2m and 3m of sea level rise, says Mr Cutler, a rise that would be catastrophic for most coastal cities.

Right now climate modellers say sea levels will rise between 61cm and 110cm by the end of the century, assuming the world keeps emitting carbon dioxide at current levels. But if Thwaites collapses faster than expected, then the amount of sea level rise caused by Antarctica could be double what is in the models.

The influence of gravity on the ocean means that sea levels will rise more in certain places. And an increase of that order would leave some cities more exposed than others, particularly the east coast of North America.

Impact of warming oceans

The good news is that the Antarctic continent is not melting that much, yet. It currently contributes about 1mm per year to the sea level rise, a third of the annual global increase. But the pace of change at glaciers like Thwaites has accelerated at an alarming rate, even though it would take thousands of years for Antarctica itself to melt.

As concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere increase to levels never before experienced by humans, researchers are trying to understand how the planet is changing. Antarctica is central to that task.

“Antarctica is by far the biggest risk,” in terms of extreme sea level rise, says Anders Levermann, a professor at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, and the author of several papers on the Antarctic ice sheet.

The big question is not whether, but how quickly, sea levels will rise. Ice takes time to melt and heat takes time to distribute through the climate system. Little is known about the physical properties of ice sheets and how they deteriorate over time, which is why understanding

Thwaites is so critical.

Mr Levermann explains that the physics involved is similar to putting an ice cube on a plate and watching it melt. “It is very difficult to say how fast sea level is rising, but it is not very difficult to say how much ice can survive on a planet that is 1C or 2C or 3C warmer, and how much the ocean will expand,” he says.

Even though emissions of carbon dioxide have fallen significantly during worldwide lockdowns, the long-term prognosis is not good. Carbon dioxide can stay in the atmosphere for a century or longer, its levels are still increasing and the planet is still warming. Recent months have seen a series of grim new milestones: last month was the hottest June on record. And in July, a heatwave in the Russian Arctic near Siberia reached a record 38C, triggering a series of devastating wildfires.

Many of the warming processes taking place on the planet are already “locked in” — like the disappearance of summer Arctic sea ice or the melting permafrost of Siberia — meaning that we may not be able to stop or reverse them. All we can do is research them, and understand what they mean for our lives.

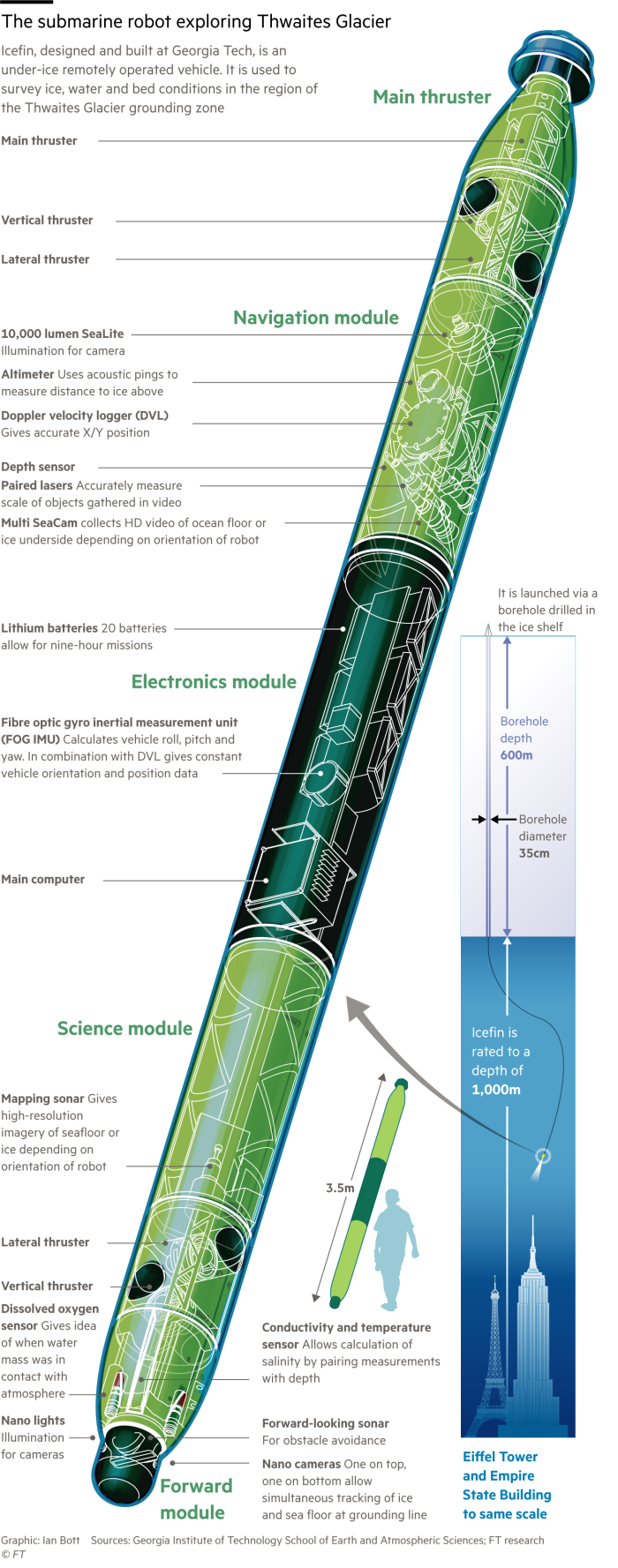

One of the more unlikely tools helping scientists in that quest is a long yellow robot named Icefin. Designed to look for alien life on Europa, one of the moons of Jupiter, it was trialled at Thwaites Glacier in December and January. Shaped like a cylinder so that it can be lowered down through a narrow hole in the ice, the robot has cameras, chemical sensors and sonar scanners. Its mission has been to reach the bottom of the glacier, where the ice meets the bedrock and most of the melting takes place.

“[This] vehicle can get into places that nothing else can really get to,” says Britney Schmidt, leader of the Icefin team and associate professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Icefin and other research teams have discovered that it is the ocean, not the air, that is the real culprit behind the melting of Thwaites Glacier. As the planet warms up due to climate change, the ocean is absorbing most of the extra heat.

In Antarctica the ice cap that covers the continent is stable right now, the melting is primarily occurring around the edges, where the ice meets the sea. This warming ocean is having an outsized impact on Thwaites Glacier, because much of it sits on bedrock that is below sea level. The lower part of the glacier, closer to the ocean, acts like a champagne cork, preventing the rest of the ice from flowing into the sea.

“If that ice is removed,” says Mr Vaughan, “that is the cork, there is the pop, and what follows is a big rush of ice that comes behind it.”

Building defences

Infrastructure planners around the world are grappling with the challenge of rising sea levels, which is complicated by the uncertainty involved. Should they be preparing for 50cm of sea level rise, or for twice that level? Finding out more about Thwaites will help to answer that question — but the answers may not arrive in time.

Coastal cities are already spending hundreds of millions of dollars to prepare. San Francisco is building defences around its airport, which sits just 10ft above sea level. In London officials are deciding when to increase the height of the Thames Barrier. Meanwhile, Jakarta has been building a string of sea walls to protect itself, although this has not yet been enough to stave off government plans to relocate Indonesia’s entire capital city.

The economic cost of rising seas is vast: as much as 4 per cent of global gross domestic product by the end of the century, according to a study published earlier this year in Environmental Research Communications. Higher seas mean more coastal flooding, damaged infrastructure, more storm surges during typhoons, and the destruction of low-lying agricultural land, as it gets infiltrated by salty seawater.

It’s much more cost-effective to prepare ahead of time for rising seas rather than wait to deal with the aftermath, says Thomas Schinko, the author of the study and a researcher at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis. “If we don’t adapt we will experience huge losses,” he adds.

But that preparation is hard if planners don’t know what to expect. “It is really about giving society a more accurate sense of how much, how fast,” says Mr Cutler of the US National Science Foundation. “How urgent is this challenge — what are we already in store for, based on the inertia in the whole global climate system?”

With coronavirus spreading across the world, the next research season in Antarctica — normally December to February — has been reduced to a skeleton staff. Antarctica is the only continent with zero cases of coronavirus, and the research teams are determined to keep it that way.

For Thwaites Glacier, that means the research teams and Ms Johnson will have to wait a bit longer to have all the answers. “We still don’t know that much about Thwaites,” says the geologist who is adamant that she will return to the glacier one day. “Most of our discoveries are yet to come.”

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario