Companies pledge all manner of assets as collateral for Covid-19 rescue deals

Robert Smith, Joe Rennison and Nikou Asgari in London

Norwegian Cruise Lines pledged its island Great Stirrup Cay as collateral, while Delta Air Lines offered take-off and landing slots © FT montage; James E. Scarborough/CC; Bloomberg

Great Stirrup Cay is an island in the Bahamas that offers tourists the chance to relax on white sandy beaches, snorkel with sea turtles or even swim with wild pigs on a neighbouring islet.

This month the island also offered fund managers enough comfort to buy almost $700m of junk bonds issued by Norwegian Cruise Lines. The Miami-based operator pledged the 268-acre Caribbean idyll it has owned since 1986 as collateral, along with a second island in Belize and a couple of ships.

It was a make-or-break fundraising to tide Norwegian through the Covid-19 crisis that has upended the tourism industry.So-called secured debt deals were once a rarity in the corporate bond market, but American companies are now pawning their family silver as never before.

More than 100 cruise ships, over two dozen theme parks and even the rights to take off and land at airports around the world are all now up for grabs, if companies fail to repay their debts or stumble into bankruptcy.

“I get that some fixed-income investor is not going to want to be the owner of a Caribbean island,” said Tim Conduit, a partner at Allen & Overy in London. “But they are going to want to be in a better position as a creditor. ‘Some collateral is better than no collateral’ is probably what investors are thinking.”

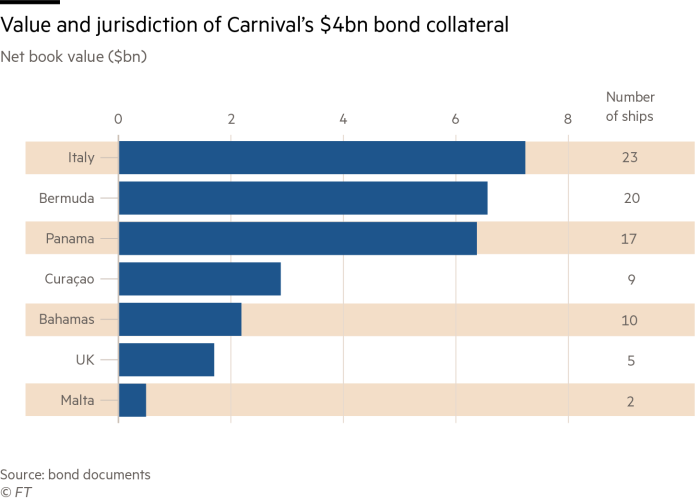

Last month companies issued $21bn of new junk-rated secured bonds in the US, according to Debtwire — a number that bankers and investors believe to be a record. Higher-rated investment-grade companies have also provided extra backing on their bonds, including the cruise liner Carnival, which began the wave of issuance in April with a $4bn debt deal backed by 86 ships.

As the coronavirus crisis intensified in March, the bond market did not seem the obvious place for corporate treasurers to turn for emergency funds. Many companies back then were talking to specialist hedge funds about potential rescue loans on onerous terms.

But after the Federal Reserve launched a package of stimulus measures that buoyed bond markets at the end of that month, Carnival’s bankers found that mainstream fixed-income fund managers were casting an eye over the company’s scores of otherwise unencumbered cruise ships.

Its deal ended up serving as a blueprint. Carnival demonstrated that with a high enough interest rate — near to 12 per cent — and a low loan-to-value, or LTV, ratio — a measure of a company’s debt to the value of the secured assets — even a company leaking $1bn of cash a month could access the bond market.

Miami-based Carnival said its ships were worth more than $27bn on paper, but also warned that finding buyers could be tough, as the market for used cruise ships is small.

“These are companies with no visibility on their revenue,” said Fraser Lundie, head of credit at Federated Hermes. “The one thing they can provide visibility on is the LTV.”

Some types of collateral are proving more alluring than others.

AMC Entertainment tapped the junk bond market for $500m in April, giving the US cinema chain enough money to ride out a total shutdown of its theatres until Thanksgiving. But investors and traders have subsequently dumped the bonds, driving their price down to just 83 cents on the dollar a month after issuance.

In part that is because of the weaker collateral behind AMC’s deal. The company owns just 62 of its 937 cinemas outright. Along with a few parcels of land including a vacant plot by a highway in Texas, they are the company’s only real physical assets.

Meanwhile, a $2.25bn bond sale from United Airlines failed to get off the ground this month, as investors expressed scepticism about the value of the ageing aircraft the US airline offered as collateral.

By contrast, Delta Air Lines raised $5bn weeks earlier with little difficulty, despite offering up few physical assets. Instead the Atlanta-based carrier pledged its rights to operate gates and fly planes from airports such as Heathrow in London or John F Kennedy in New York.

Roger King, an analyst at research firm CreditSights, described these take-off and landing slots as “fuzzy collateral,” saying their real value to debt investors would be tested only by bankruptcy.

“It’s like a bottle of old wine — you never want to open it up, because you don’t want to know if it’s bad or not,” he said.

Some investors fear that even traditional hard assets such as boats and planes could prove challenging for investors to enforce their claims on. None of the 86 ships Carnival pledged to bondholders, for instance, is registered in the US. The ships are instead flagged in jurisdictions including Bermuda, Panama and Curacao.

That means that seizing the ships to sell them could prove tricky. “The security is governed by the country the asset is situated in,” said Shweta Rao, an analyst at research firm Reorg.

“Enforcing your security on a ship is not easy.”

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario