The aim is to emerge with a sterling reputation, staff trust and solid financial base

Robert Armstrong

© Ingram Pinn/Financial Times

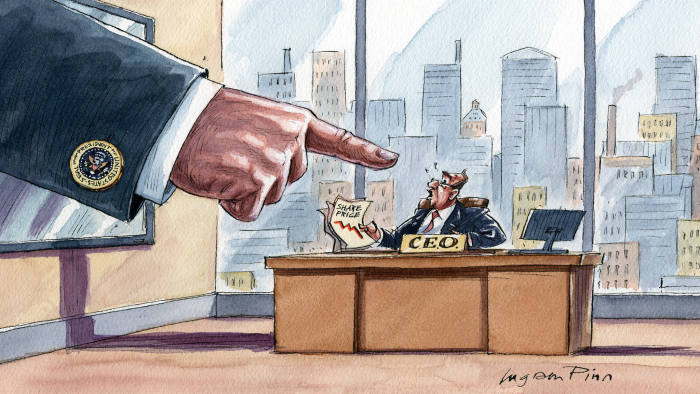

© Ingram Pinn/Financial TimesIn a time of crisis, what does business owe the public good?

And what can the government require companies to do? If the crisis is deep enough, the answer to the latter question is: almost anything.

In his 1942 State of the Union address, US president Franklin D Roosevelt proclaimed “overwhelming superiority of armament” a requirement for victory in the second world war.

He ordered the construction of an astonishing 60,000 planes, 45,000 tanks, 20,000 anti-aircraft guns and 6m tonnes of shipping capacity that year.

To reach those goals, the Office of Production Management banned the manufacture of passenger cars, diverting all of Detroit’s manufacturing capacity to the war effort.

In the coronavirus pandemic, the US government’s demands have been lighter — but less predictable. Last month, President Donald Trump signed a memo ordering General Motors to “accept, perform, and prioritise federal contracts for ventilators”.

The memo said GM had been “wasting time”, and Mr Trump tweeted that it was “always a mess with” chief executive Mary Barra.

A similar memo instructed the secretary of homeland security to “use any and all authority” to secure N95 face masks from the manufacturer 3M.

It came after Mr Trump said 3M would have “a hell of a price to pay” if it did not prioritise US customers.

Both companies quickly came to agreements with the administration. A GM factory will soon start turning out ventilators, and 3M has agreed to send some 166m masks to the US from its plants abroad. It may not always be so easy, however.

We are at a moment of cautious optimism about the virus’s trajectory. But the worst-case scenario, in which repeated outbreaks cripple the US economy for another six months or more, may yet play out.

In that case, the federal government will ask much more of a lot more companies.

The greatest risk then would come not from Mr Trump’s tweets and temper but the lack of institutional structures. FDR put in place systems that filtered the executive will through agencies, boards and Congress. Business executives were not just consulted; they led the efforts.

The first chair of the Office of Production Management was former GM president William Knudsen.

The rapid rise of coronavirus has made it difficult to construct that kind of structure. This may change in time, but so far Mr Trump has kept power closely held. His supply-chain task force is run by a Navy admiral, not a business leader, and it gives the presidential son-in-law, Jared Kushner, a key role.

Complicating companies’ relationship with the government is the fact that the biggest challenge this time is not going to be manufacturing equipment but supporting the economy through the shutdown. When the government tells you to make guns to kill Nazis, and offers to pay, you do it.

When it tells you to administer, for a fee, the coronavirus bailout programme for small business, as US banks have been asked to do, it is almost as easy to say yes.

If the next ask — implicit or explicit — is about whether companies can lay off staff or set pay, responding will be harder.

There is no guarantee that what the government asks will be reasonable.

But two principles will help see companies through.

First: don’t wait.

The best way for an industry to avoid landing on the wrong side of an unpredictable government’s agenda — or of public opinion — is to act first. We have seen some of this already.

The biggest US banks announced as a group that they would suspend buyback programmes to preserve capital for lending.

This was not a costless decision. With banks’ share prices low, buybacks can deliver big gains to shareholders, and many bank leaders were confident they had plenty of capital. But the decision was wise.

Shares can always be bought back after the crisis has passed, and acting early aligned the banks with regulators and the public good. We will need to see similar and bolder actions, if the crisis worsens.

The American industrial response to coronavirus will almost certainly be better if companies lead and the president follows.

But this can only happen if companies follow a second principle: look to the horizon. In normal times, there is a healthy tension between short-term and long-term results. In a crisis, only the long term matters.

The goal must be to contribute what you can, and emerge from the crisis with a sterling public reputation, employee trust and a strong financial foundation. All this will pave the way for a better relationship with government, too.

In 1944, Sewell Avery, chairman of the department store Montgomery Ward and an ardent free marketeer, lost patience with the government rules for negotiating with the store’s unions.

“To hell with government!” he shouted.

He was physically carried out of his office by national guardsmen. Mr Avery eventually got his company back.

But today’s chief executives might want to consider how a similar failure to see the big picture would play out in the age of social media.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario