Washington’s East of Suez Moment

By: Caroline D. Rose

In January 1968, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson delivered an address to the House of Commons in which he formally announced that the United Kingdom would finally withdraw its military from locations east of the Suez Canal, namely Singapore and Malaysia and, within three years, the Persian Gulf.

It was a question London had grappled with since 1956, when currency devaluation, high-interest postwar debt, anti-colonialism sentiment and diminished imperial influence forced the government to reevaluate its defense posture. The “East of Suez” moment brought an end to one of the world’s longest-reigning imperial powers.

Just over 50 years later, the United States is facing a similar moment, not in the form of a waning empire but amid a viral pandemic. The differences are apparent, of course: The U.S. is still the world’s strongest military power, still boasts the largest defense budget on the planet and still maintains a large military footprint throughout the world.

And though it has its share of economic issues, it is not in the throes of a currency crisis, nor are any of its problems uniquely American, thanks to the coronavirus, which is raising unemployment and slowing economic growth across the world.

In fact, the pandemic may have given policymakers in Washington an opportunity to accelerate the reduction of forces in the Middle East and thus change its regional defense posture in the long term, something it has tried but failed to do for the better part of a decade. Yet, within a span of three months, U.S. personnel have begun to pack up from a number of bases across the Levant, signaling Washington may seriously be beginning the process of withdrawal.

And though this will not mark the end of U.S. imperial power as it did for the U.K. in 1968, it will mark the end of an era in which Washington dominated the Middle East directly through the use of military force.

With disengagement comes a reconfiguration of Middle Eastern geopolitics, creating opportunities for regional, self-reliant powers to consolidate influence and advance defensive interests.

A Pattern Emerges

The forever wars the U.S. has carried out for the past two decades have been the defining characteristic of the post-9/11 era. What started as a response to terrorist attacks became a permanent presence. Mission creep became the norm. Operations in Iraq, Afghanistan and later Syria shifted objectives and sunk into long-term, seemingly indefinite commitments.

Getting into Middle Eastern wars is easier than getting out – just ask the Brits, the French and the Soviets. But since the 2008 election, the U.S. has made it a priority to do just that, partly as a result of war fatigue at home and partly because its defense priorities lay elsewhere. In the past few years, the Pentagon has opted to shift to developing operational strength against emerging threats, i.e. Russia and China.

Countering conventional threats from China and Russia gradually came to overshadow counterterrorism objectives in the Middle East. As the U.S. sought to delegate security responsibility to Middle Eastern nations, it fell into a credibility trap, caught as it was between maintaining influence in the region, preventing the formation of security vacuums and promising outright to withdraw. This has sucked the U.S. into maintaining – even increasing – militarized engagement in the Middle East over nearly two decades.

Washington has sought to implement low-cost strategies to create self-reliant actors that would tip the scales of the region’s balance of power and take on greater responsibility in countering transnational threats like Iran. This has led to partnerships with local militias such as the Kurdish peshmerga and the recruitment of European international allies, especially in the fight against the Islamic State. But even these low-cost strategies have begun to fetch a high price.

Once a power starts reducing its presence and operational capabilities, its remaining personnel become more vulnerable to attacks.

Increased threats to units, now smaller in size, have required deeper consideration to decide whether their presence is worth it and, if it is, at what point it is not. As the U.S. reckons with this in Syria and Iraq, Washington has begun to question the point of its 20-year-long Middle East doctrine.

Take Iran, for example. This past January, the U.S. and Iran very nearly confronted each other. Following tit-for-tat rocket strikes between U.S. coalition forces and Iran-backed Shiite proxies in Iraq, the U.S. assassinated Qassem Soleimani, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ top commander, and Abu Mahdi Al Muhandis, the deputy commander of an Iraqi militia on Tehran’s payroll.

Iraq – already under the strain of monthslong protests against foreign influence and corruption – condemned the U.S. strikes as a violation of its national sovereignty and voted in parliament on Jan. 5 to request U.S. forces to leave the country.

On Jan. 9, Iraq’s caretaker prime minister requested the U.S. send an envoy to Baghdad to discuss conditions, but the U.S. refused to even entertain the prospect of withdrawal. To be sure, withdrawing from Iraq fits squarely into the U.S. national interest, but Washington did not want to appear to yield easily. To save face, the U.S. stayed put.

The coronavirus pandemic has therefore given the U.S. an out. In fact, it has already begun to withdraw its forces. Over the past two months, the U.S. military has handed over four bases to Iraq, even its most important one in the country at al-Qaim, located near the Syrian border.

Some U.S. personnel have been transferred outside Iraq to larger U.S. bases in Kuwait and Syria, some deployed home and some consolidated to U.S. bases in more secure locations in Irbil and Baghdad.

Iraq’s former caretaker Prime Minister, Mohammed Allawi, reported that during his brief tenure, U.S. embassy personnel communicated to Baghdad that the Pentagon was maintaining a quiet two-year withdrawal timeline, with plans to draw down the majority of American forces in Iraq by 2022.

Again, the pattern is clear: The U.S. draws down, its forces become more vulnerable and attacks continue, prompting further reductions and inciting more resentment. In Iraq, as the U.S. continued its withdrawals and personnel transfers, Iran-backed militias like the Popular Mobilization Forces and Kataib Hezbollah continued to carry out attacks on Camp Taji base and even the U.S.’ oil company Haliburton in Basra province.

The U.S. responded with retaliatory strikes on pro-Iran militia weapons storage facilities at an Iraqi army base in Babil province, an airport in Karbala, and PMF headquarters. The fact that the U.S. characterized its response as defensive fell on deaf ears in Baghdad, which grew increasingly angry with American barrages.

In Syria, the U.S. has already begun to prepare its partners for a life without Washington, especially as they shoulder more of the load for combatting the Islamic State. Posts in the northeast have started transferring missions and responsibility for certain operations to Kurdish partners.

The U.S State Department has sent delegations to meet eight Syrian Kurdish parties to encourage cross-party Kurdish unity and discuss the Kurds’ strategy in a postwar Syria, particularly when facing rivals – Russia, Turkey and the Assad regime – without U.S. ground support.

Just this week, U.S forces designed a new counterterrorism military unit that shifted responsibility to the majority-Kurdish People’s Protection Units, or YPG, in al-Tanf along the Syrian border with Jordan. The U.S. has increased its arms and financial contributions to Kurdish forces to strengthen their long-term viability as well, giving the YPG $200 million for ongoing counterterrorism operations.

The Levant’s New Geopolitics

Even more of a burden will be placed on other U.S. partners in the region – Saudi Arabia, Israel and Turkey – to mitigate a shared threat: Iran. U.S. allies may resent the U.S. for “leaving” the region but not so much that they will set aside their own differences with Tehran if it decides to fill the resultant security vacuum.

But a Levant devoid of American ground forces doesn’t necessarily translate to all-out conflict. Rather, it will transform into a buffer zone as its neighbors advance their defensive interests.

The Levant is enveloped by the region’s emerging powers: Turkey, Israel, Saudi Arabia and Iran. While religiously and ideologically poles apart, Turkey, Israel and Saudi Arabia had counted on the U.S. in their shared interest of disrupting Iran’s arc of influence across the Levant.

Absent U.S. boots on the ground, U.S. allies will look to the Levant as a strategic zone crucial to keep neutral. For Israel, this will mean controlling border regions with Lebanon and Syria to defend itself against Hezbollah, intensifying strikes on Hezbollah’s strategic locations and cracking down on Iran-affiliated groups in Israel such as Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad.

Saudi Arabia will try to boost its credibility in the Levant as the leader of Sunni Islam, increasing its support of Sunni factions in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon as a counterweight to Iranian Shiite influence.

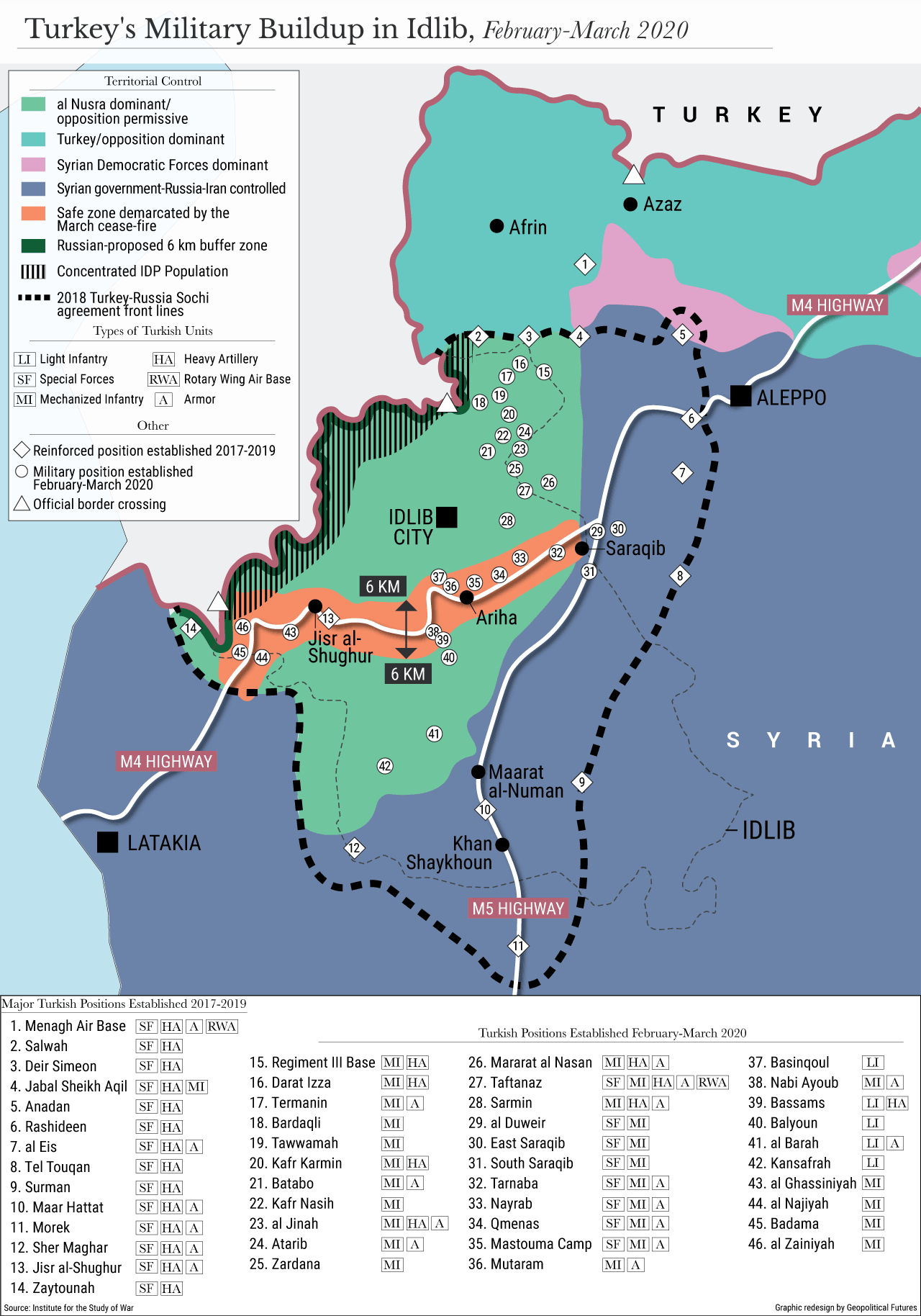

Turkey, in particular, will feel compelled to further secure its eastern frontier, establishing zones of influence along its border with Iraq and Syria and advancing existing operations in Idlib and northeast Syria and Operation Claw in Iraq, to shield against Kurdish groups Ankara classifies as terrorists, Iranian proxies and part of the Russia-Syria alliance.

The prospect of an American disengagement sets up an interesting new reality in the greater Middle East. The U.S. will not withdraw entirely from the region, likely retaining its bases in the Gulf and maintaining air and naval superiority.

But on land, American dominance and its capacity to conduct ground operations will fade, to be replaced with economic instrumentalization and dependency on standoff air and naval strikes. The deficit of American influence in the region will spur a geopolitical reshuffle among Middle Eastern powers, solidifying alliances against regional rivals and reshaping the Levant into a strategic buffer zone.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario