By: Allison Fedirka

Mexico is bracing for a serious economic recession this year, much like the rest of the world.

But unlike many other countries, the Mexican government is not meeting the event with an abundance of bailouts, tax breaks or other fiscal measures.

Instead, Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (popularly known as AMLO) has opted to stay the course with his plans of austerity and social development funding, much to the chagrin of big business.

He has made it clear that his goal for combating the recession is to avoid sovereign debt and mitigate the impact felt by the country’s poor. Lopez Obrador is facing three fronts in his battle against a recession in Mexico: the country’s formal, informal and black market economies. And his decision to focus on propping up and reining in the informal economy through continued social development funding is more than just a continuation of adherence to political policy. It also reflects that the government is unable to effectively address the other two economies on its own.

The Three Economic Fronts

Lopez Obrador’s strategy to confront the economic recession preserves his big-picture plan to “transform” the Mexican economy and wrestles with the fact that the Mexican economy can be clearly divided into three distinct sub-economies, each playing by its own set of rules. The formal economy is characterized by services, finance and high-end manufacturing with intricate supply chains.

It generates 77.5 percent of the country’s gross domestic product and is concentrated in the central and northern parts of the country. The informal economy — a “gray zone” not taxed or regulated by the government but still legal — generates 22.5 percent of the country’s GDP and is characterized by precarious employment, basic manufacturing and low wages. It exists in much higher concentrations in the country’s south.

The black market economy, run by organized crime, is prevalent throughout the entire country. Its economic contribution is not clearly known given the illicit nature of its activities, but recent estimates put Mexican drug sales to the United States at $19 billion to $29 billion annually.

Despite its illegality, the black market injects a massive amount of capital into the economy, which generally speaking is a good thing. On the other hand, it also deters investment and infrastructure development and breeds extortion, corruption and violence. The result is a mixed bag of economic effects that is not easy to define or calculate.

AMLO’s proposed solution for dealing with the segmented nature of Mexico’s economy involves diminishing the economic and development disparities across the country through youth education and job training programs, labor-intensive infrastructure projects, support for small businesses, anti-corruption measures and government austerity.

In other words, he is attempting to reduce the informal economy and merge it with the formal economy.

His approach has been controversial and viewed by the opposition as contrary to the ultimate objectives of developing and growing Mexico’s economy. Indeed, the segmented nature of the country’s economy makes it extremely difficult to pursue a policy that helps one segment without hurting the other two.

But in the face of the recession, the government has opted to direct the few funds it has toward the informal sector, an approach that aligns with long-term goals and exists as the most viable short-term solution available.

The Formal Economy: Severe Limits

Mexico’s formal economy has a high degree of exposure to external forces and is therefore largely out of the government’s control. For starters, the Mexican economy is largely dependent on the health of the U.S. economy.

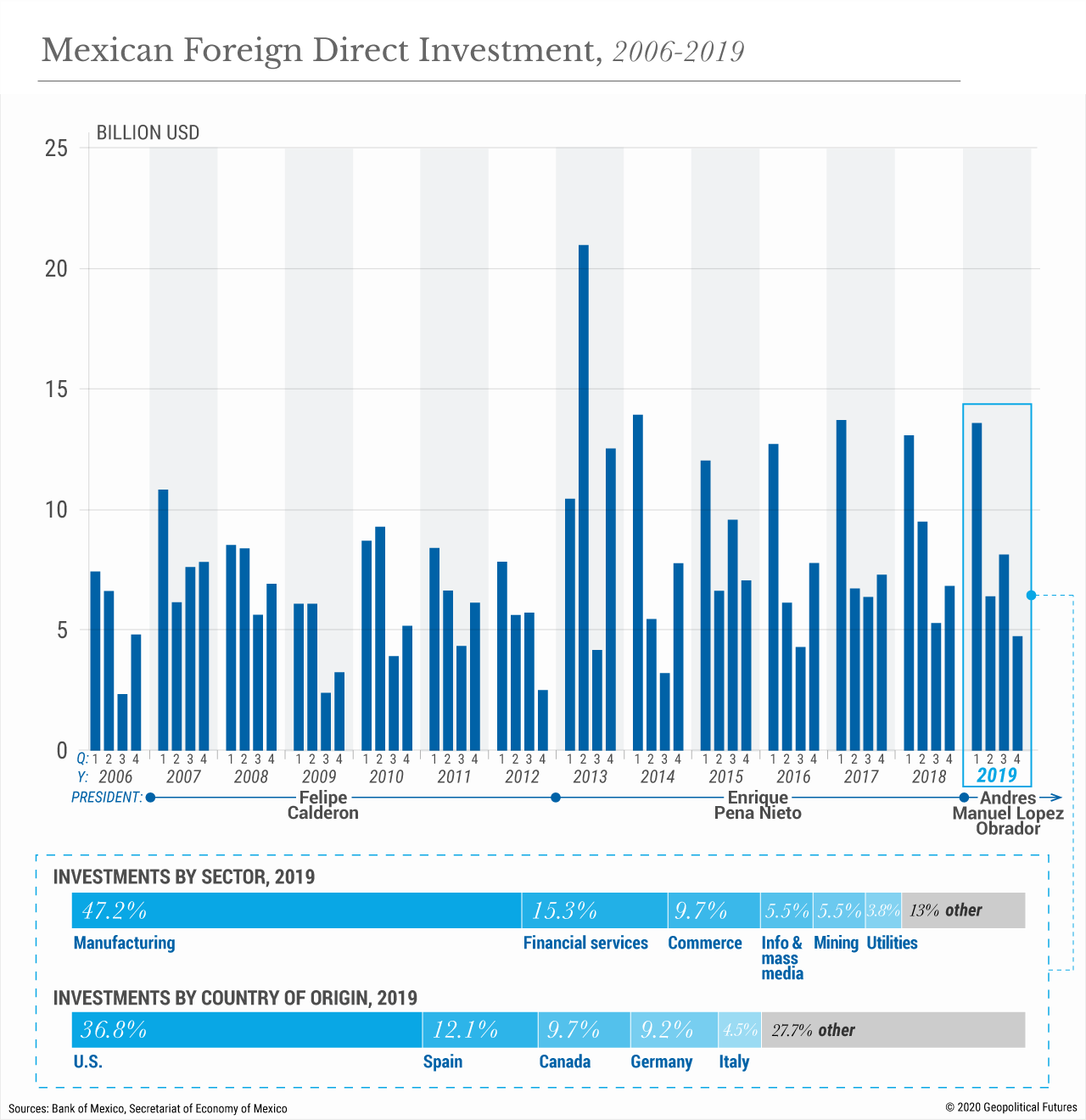

Mexican exports to the United States are equivalent to about 31 percent of the country’s GDP, and the United States is the leading supplier of foreign direct investment to Mexico. Remittances, which totaled $36.05 billion last year, are Mexico’s largest source of U.S. dollars, and 95 percent come from senders in the United States.

When the U.S. economy performs poorly (or restricts border crossings), the effects are often amplified in the Mexican economy. The International Monetary Fund expects the U.S. economy to contract 5.6 percent this year, and new unemployment claims in the country at the time of publication stand at 22 million.

For Mexico, this means that there are far fewer buyers of Mexican goods and that the country can’t trade its way out of the crisis, even considering the strong decline in the peso’s value relative to the dollar so far this year.

To escape its mild 2019 recession, Mexico had planned to turn to foreign direct investment in 2020. And even before a global recession became imminent, the government was struggling to attract foreign investment over concerns of regulations, crime and general doubts over management. Now, the United Nations estimates that foreign investment will drop by 30-40 percent globally this year.

For Mexico, this means investment will be difficult to come by and require fierce competition with others. Foreign investment is no longer a viable option to stimulate the economy. Lastly, other major financial sources, such as oil and tourism, not only remain out of Mexico’s control but have poor prospects this year.

Admittedly, state-owned oil company Pemex has been struggling for years, but even in the company’s best-case scenario, it can do little to address low oil prices, let alone change them.

As for tourism, travel restrictions and personal fears mean the cancellation of many summer trips.

The Mexican government has offered little to mitigate the recession’s impact on the formal economy because the influence of external factors will outweigh much of what it can offer. The government says it only has about $10 billion available from various rainy day funds. This means the bailouts, tax breaks and fiscal stimulus called for by businesses in the formal sector cannot be executed on a scale that would have an impact on a $1.3 trillion economy.

Effectively stimulating an economy takes massive amounts of money, which often means taking on debt — and the concern over government debt in Mexico predates AMLO. The government currently does not have enough reserves to cover its debt in the event of an emergency, and incurring new debt would make matters only worse.

Additionally, spending money on the formal economy would largely put the two other major segments of the economy on the sidelines. The government’s financial authorities did loosen liquidity rules on banks, which they assert are well equipped to handle the pending economic crisis, but aside from that, it has taken a largely hands-off approach.

The Informal Economy: Opportunity for Impact

The Mexican government has directed its efforts toward the informal economy because its potential for impact is higher and the informal economy plays a critical role in the workforce. Mexico defines the informal economy as one that includes any economic activity that is legally produced and marketed but the production or distribution units are not formally registered.

It also includes all economic activities that operate from family resources, such as micro- and small businesses that are not constituted as companies. Because informal workers tend to have lower-quality jobs, lower wages and no insurance compared to those with formal-sector jobs, they are more vulnerable to recession.

And since the latest official figures from the end of 2019 show that Mexico’s informal sector employs 56.2 percent of all workers, a sizable portion of the country’s working population is highly vulnerable to recession.

The actions the Mexican government has taken to mitigate the impact of a recession on the country’s economy have focused on supporting the continued employment of informal workers.

Earlier this month, the government said it would provide a 25,000-peso ($1,000) credit for small and micro-companies that have retained employees and not reduced wages, offering low interest rates that increase slightly by company size.

The plan allows for a million total recipients, though an estimated 5 million will request access, and money will arrive in May and June.

This low-interest-rate credit will need to be paid back in three years, with payments starting after the fourth month. Lopez Obrador also announced additional credit for the creation of 2 million more formal jobs this year, but such a project was already in the works prior to the global recession.

One wild card that could impede the government’s task of easing the recession’s impact is remittances, which play a key role in many household incomes, particularly in poor segments of the economy.

BBVA estimates that, this year, remittances will decline by 17 percent to $29.9 billion due to the recession and mass unemployment in the United States. Nevertheless, from the government’s perspective, it’s still more cost-effective to support working programs now than deal with millions of people eventually out of work amid economic collapse.

The Black Market Economy: A Very Large Shadow

Though Mexico’s organized crime groups are not often considered in terms of their contribution to economic activity, they must also be factored in to efforts to combat the recession. For better or worse, the large scale and high value of their operations do create jobs and support economic activity at local levels.

The pervasive nature of organized crime means it touches the pocketbooks of hundreds of thousands of Mexicans. And these groups are not immune to the recession, though they are positioned better than most to confront it.

Like many multinational companies, organized crime groups in Mexico experienced supply chain disruptions with the slowing global economy, particularly with respect to the chemical precursors from China used to make fentanyl.

The disruptions hurt major fentanyl suppliers, such as the Sinaloa and Jalisco New Generation cartels.

Meanwhile, alternative revenue flows, including human trafficking, fuel robbing and extortion, are not currently available due to increased border restrictions, low oil prices and businesses going on hold for quarantine.

Of course, the addictive nature of drugs means that demand in that area remains. And that, in turn, has meant an increase in price due to supply chain shortages and stricter border measures.

AMLO’s government will have to face the threat of increased social and political encroachment by organized crime. The recession and health crisis have already presented organized crime groups with opportunities to intensify their presence in socioeconomic gaps in place of the government.

Big-name cartels like Golf, Jalisco New Generation and Sinaloa have also started community outreach and charity programs to provide locals with goods at a time when supplies and funds are scarce.

In this area, AMLO finds himself extremely limited in terms of what he can do to combat organized crime, particularly on the economic end; freezing assets will not reach a sum high enough to stop operations anytime soon.

This is one major reason that AMLO reiterated his plans to continue social development funding and welfare programs, which are intended (at least on paper, over time) to undermine the hold that organized crime has on local communities.

That said, the president knows this remains a weak point for the government because it cannot throw money around as easily as the cartels.

The Only Real Option

Lopez Obrador was forced to choose sides in preparation for mitigating the impact of Mexico’s deeper recession, and his outlier approach of rejecting stimulus measures reflects the reality of three very distinct economic segments, none of which overwhelmingly dominates the others.

He does not have the funds or enough control over the formal economy to risk stimulus; he does not have the reach or security ability to take on organized crime.

What remains is the country’s informal sector, where the bang for the buck (or punch for the peso) is larger, and where efforts generally align with longer-term goals of integrating the informal economy into the formal one, thereby improving economic standards for Mexico’s lower socioeconomic classes.

This may not be considered the ideal move by many, but it’s AMLO’s only decent option.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario