By: Allison Fedirka

The unanticipated decline in global trade has naturally led countries to rethink their trade relationships.

Trade blocs and other methods of economic integration originally meant to achieve peace and prosperity are now seen as impediments. Of course, countries aren’t going to stop trading anytime soon, but it’s becoming clear that the post-Cold War era models characterized by interdependence and increasingly segmented and diversified supply chains appear to be on their way out.

And though every country will make the necessary adjustment at its own pace, some in South America are already doing so.

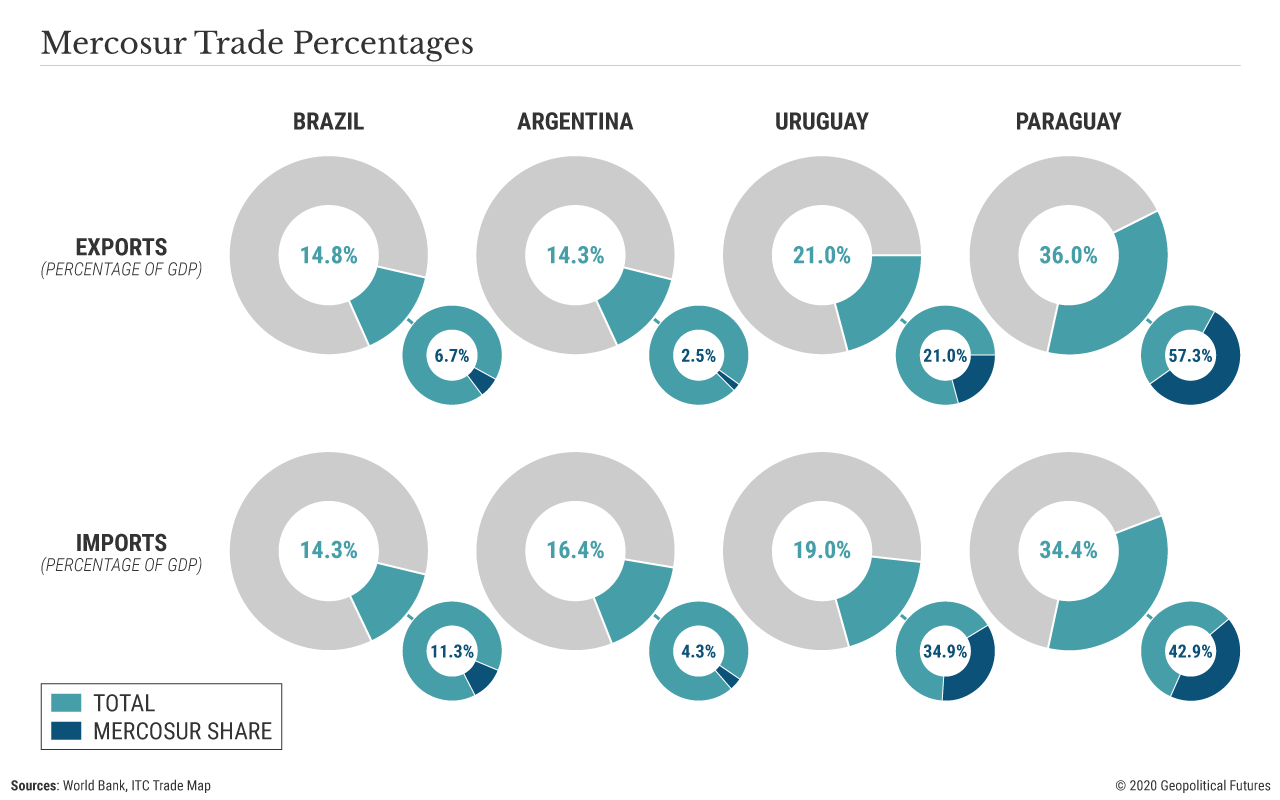

Brazil and Argentina – the region’s two largest economies – have taken actions that will redefine Mercosur, their framework for bilateral and foreign trade.

In redefining Mercosur, Argentina and Brazil will also redefine their relationship with one another and the rest of South America.

Argentina and Brazil view the role of trade and foreign business from fundamentally different positions.

Argentina’s economy has been in decline for years. Its gross domestic product contracted 2.5 percent in 2018 and 2.2 percent last year. The government also has about $65 billion worth of debt it desperately needs to renegotiate.

President Alberto Fernandez, who inherited most of this debt from his predecessor, has rejected austerity on the grounds that it harms the lives of Argentine citizens and so has reverted to a strategy of greater state funding and management of the economy.

Thus is Argentina’s trade dilemma: The presence of foreign goods threatens to replace domestic-made products or raise prices across the board, thereby undercutting local producers and reducing consumption of domestically made goods.

Brazil has also struggled to jumpstart its economy after its last recession. But its plan to spark domestic economic growth involves increasing exports of Brazilian-made goods. It also has extensive plans to privatize business and sell off other assets – a move to get more revenue and make the economy run more efficiently.

For Brazil, trade and foreign participation in the economy are cornerstones of the government’s revitalization efforts, and though the coronavirus pandemic has put some of its components in jeopardy, trade is still a priority.

Brazil and Argentina's different stances on trade explain their different approaches for shaping free trade negotiations. On April 24, Argentina’s Foreign Ministry announced that it would no longer engage in Mercosur’s free trade talks with other countries, though it would complete and honor agreements with the European Union and the European Free Trade Association.

Argentina said it needed to prioritize its own needs and that it didn’t want to hold up the process over issues that are incompatible with its own priorities.

The government later had to clarify that it had no intention of leaving the bloc – which currently regulates intra-bloc trade – and wanted to maintain regional ties.

Argentina’s presumed withdrawal was strongly welcomed by Brazil, which outgrew Mercosur's objectives long ago. Argentina’s move effectively clears the way for the world’s eighth-largest economy to engage in free trade talks unimpeded. (Paraguay and Uruguay will gladly follow deals it can get through Brazil and welcome the flexibility for themselves too.)

The Brazilian government has already started discussing plans to revise Mercosur regulations in Brazil’s favor, codifying Argentina’s decision and allowing it to navigate talks without Argentina’s agreement (unanimity has long been a requisite for Mercosur agreements) even if Argentina finds itself ready to reengage in foreign trade talks in the future.

This not only addresses Brazil’s short-term needs but creates more flexibility for Brazil to act on its own down the line.

However, redefining how Mercosur conducts trade talks necessarily brings into question the future of ties within the bloc. In its nearly 30-year existence, Mercosur has never come close to achieving the four progressive goals it set out to achieve: establish a free trade zone with no restrictions on the circulation of goods among member states, form a customs union in which common external tariffs would be uniformly applied across the group, create a common market to allow free movement of labor and capital, and synchronize member states’ macroeconomic and trade policies.

Mercosur has established relatively free trade practices and components of a customs union, but institutional constraints and domestic economic crises have always prevented it from doing more.

To overcome the gridlock, the bloc has devised ways to side-step problematic restrictions. For example, each member can select goods it believes could be harmed by lifting tariffs and can continue charging duties on those products within the bloc. In other words, Mercosur is not truly a free trade zone because it has allowed its members to impose hundreds of tariff restrictions.

If Mercosur were to completely fall apart, its members would still hold special trade status because of accords they signed under the ALADI framework, which laid the foundation for Mercosur.

These agreements opened specific market segments to free trade-like status and were used to create a basic framework for a common market. Dissolving Mercosur would not dissolve these previous agreements, though it would lift the restrictions on foreign trade negotiations and bring intra-bloc trade back to the bilateral level.

The Argentina-Brazil relationship is the heart of Mercosur. The bloc itself is a product of the post-Cold War order in which economic and political forces in the region increased global trade and led to the collapse of military governments in South America.

When military rule ended in Argentina and Brazil in the 1980s, the struggle for regional dominance and competition for external markets and over nuclear energy development that had typified their relationship cooled down.

Both were facing economic uncertainty and dealing with political transition, and they couldn’t afford to continue the rivalry any longer. Their vulnerabilities and interests aligned, and Buenos Aires and Brasilia overcame their political differences and decided to pursue economic integration.

The inclusion of Paraguay and Uruguay – originally created to serve as buffer states between Argentina and Brazil - further helped defuse tensions between the two.

Hence the creation of Mercosur.

The bloc is no stranger to controversy, but the conditions in which Argentina and Brazil face controversy have shifted. Over the years, they have managed to keep the bloc together through political negotiations even when they faced financial and monetary crises.

Now, their interests are simply not as aligned. Despite its current economic challenges, Brazil dominates the bloc.

Whereas its size and general economic trajectory allow it to pursue a more global agenda, Argentina’s domestic problems keep it inwardly focused and unattractive to outside business.

Argentina understands it is the weaker of the two, as demonstrated by its decision to hold back from foreign trade talks. It bowed out because it knew it could not negotiate a free trade deal with other countries under current conditions.

But it did not want to risk the regional ties the bloc offers; by giving space to Brazil to negotiate trade deals on its own, Argentina moved to preserve what would remain of the Mercosur agreement and trade benefits.

For Brazil, however, there is little value in preserving the regional-level agreements. The government of Jair Bolsonaro has been chipping away at Mercosur since taking office and even used the ALADI framework (not Mercosur) as the method of choice to coordinate COVID-19 relief materials among the member states.

The disintegration of Mercosur, slow as it may be, will shift regional dynamics further away from integration. Until now, countries have hesitated to violate the bloc’s rules because of the consequences they could face.

But crises such as Venezuelan migration and the coronavirus pandemic have forced them to start walking away from regional blocs in favor of pursuing their own national interests. The political consequences of not doing so are greater than the consequences of breaking rank.

In this context, buffer states such as Paraguay, Uruguay, Bolivia and Ecuador will increasingly return to this role as old rivalries and tensions between the larger nations could reemerge.

Reconstruction of national economies will be as much an economic decision as it is a political one.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario