by: Montana Skeptic

Summary

- A few weeks back, I wrote of a trader whose goal was discovering where the big money is moving right now and reaching out to grab some.

- Today is something completely different: A focus on two financial industry veterans, Grant Williams and Stephanie Pomboy, who think in big picture terms.

- Williams and Pomboy see the era of globalization unwinding just at the moment when government spending and central bank interventions are reaching a frenzy.

- It's all unsustainable. It will all come crashing down. But how will it end? And how can an investor guard against the damage, or even profit from the opportunity?

- Join me as I eavesdrop on a conversation between these two. And then conclude with a word about Tesla.

- Today is something completely different: A focus on two financial industry veterans, Grant Williams and Stephanie Pomboy, who think in big picture terms.

- Williams and Pomboy see the era of globalization unwinding just at the moment when government spending and central bank interventions are reaching a frenzy.

- It's all unsustainable. It will all come crashing down. But how will it end? And how can an investor guard against the damage, or even profit from the opportunity?

- Join me as I eavesdrop on a conversation between these two. And then conclude with a word about Tesla.

Tesla (NASDAQ:TSLA) is not the only thing going on in the world. It's not even the most important thing going on in the world. Indeed, in the big scheme of things, Tesla is a tiny thing.

An emblem, surely, of the financial and monetary excesses of our times, and of lax regulatory standards, and of the reflexive virtue signaling that has come to substitute for serious thinking. But not an important thing.

The Important Things

The Important Things

Today, I want to explore truly important things. Not as important as good health and happiness, but perhaps next in line: The economic health of our nation and world, which affects the livelihood and wealth of each of us, and will shape our future.

I want to detail a recent conversation between Grant Williams and Stephanie Pomboy because I believe the topics they addressed have immense implications for investors everywhere.

Who is Grant Williams? It's impossible to pin him down with a simple description. In a brief biographical sketch, he describes himself as "a keen student of history, markets, politics, and, above all, human nature."

These days, among other things, he's the author of a superbly written newsletter called Things That Make You go Hmmm, which I began reading several years ago.

And Stephanie Pomboy? She is founder of a research firm called MacroMavens which, as its name implies, employs its analytic approach to identify macroeconomic events "and steer our clients around them - well ahead of the curve."

Her firm famously gave its clients early warning about the bursting of the housing bubble, which was a major contributor to the 2008 Great Financial Crisis.

Pomboy is one of scores of fascinating people whom Grant Williams keeps on his radar screen, regularly corresponds with, and periodically interviews.

Pomboy and Williams had their discussion last Friday (April 10) in what Williams calls a "Hmmminar," which are online video interviews he's conducting with personalities from around the globe during the coronavirus lockdown.

As I write this, Williams has posted 10 of these Hmmminars, and has several more scheduled.

The Discussion's Backdrop

As I write this, Williams has posted 10 of these Hmmminars, and has several more scheduled.

The Discussion's Backdrop

On April 9, one day before Pomboy and Williams spoke, the U.S. Federal Reserve announced it would begin including, in the corporate debt it was purchasing to backstop financial markets, so-called junk bonds. The Fed set the size of the purchasing facility at up to $750 billion.

While the Fed had earlier indicated it would purchase only investment grade corporate debt, the April 9 announcement relaxed that rule by announcing purchases of debt that had an investment grade rating before March 23 but had since been downgraded to junk status.

For the junk debt to qualify, it would have had to be rated BBB-/Baa3 (the lowest rankings of investment grade debt) as of March 22.

For the junk debt to qualify, it would have had to be rated BBB-/Baa3 (the lowest rankings of investment grade debt) as of March 22.

Pomboy had been tracking the number of credit rating downgrades to junk status, both for particular debt issuances and for companies, in the weeks leading up to the Federal Reserve announcement. She found more than 500 such issuance downgrades since March 22 and another 12 downgrades of particular companies.

As more companies revise their earning guidance, or begin reporting Q1 results, it's all but inevitable that there are more downgrades to come.

Two days before the Fed announcement, Pomboy had published a research piece called Trump Card(s), in which she wrote about where we have been and where we are going.

Even Before Coronavirus, Markets Were In Trouble

Both Pomboy and Williams have for years been warning about the increasingly untenable position of both U.S. and international markets, which they view as having long term, fundamental problems.

While any description I offer will be a simplification, I think it's fair to say both share several key views:

While any description I offer will be a simplification, I think it's fair to say both share several key views:

- Central banks with their various "quantitative easing" projects and reluctance to raise rates have repressed interest rates, thus depriving financial markets of what is perhaps the most important price - the true price of risk.

- With interest rates beaten down and spreads between investment grade debt and junk bonds shrinking to historic lows, investors have increasingly been forced to buy equities (the so-called TINA effect, for "There Is No Alternative"). Predictably, this has driven up the price of equities.

- Low interest rates also have encouraged corporations to take on ever more debt, often using some of the proceeds to buy back their own stock. This, too, has contributed to ever-rising equity prices, while making corporations more vulnerable in any downturn.

- Meanwhile, the U.S. government and other national governments have continued running large deficits and piling on ever more debt. State and local governments, attracted by low municipal bond rates, have added to their debt as well. The governments have been enabled to do so, thanks to the interest rate suppression engendered by monetary policy.

- All the while, despite the longest-running bull market in history, unfunded public and private pension obligations have been increasing. Compounding the problem has been the paucity of investment grade debt at yields adequate to meet the pension funds' needs, which has forced the funds into ever-riskier investments.

While the coronavirus shock is unprecedented in its nature and scale, both Pomboy and Williams view it as accelerating and deepening problems that were already bound to emerge.

The Dutch Boy At The Dike

As noted, Pomboy has been tracking the accelerating descent of the bond markets "fallen angels" and so viewed the Fed's decision to begin buying even sub-investment grade debt as inevitable. She and Williams agreed that $750 billion in bond purchases won't be the end of it. Both expect the Fed's bond buying program to increase in both size and scope and believe it may soon include bonds that were below investment grade even before March 23.

Williams wondered whether the Fed will soon begin buying equities as well as debt. That, of course, seems unthinkable now, but it was only a few months ago that the idea of the Fed buying junk bonds was unthinkable.

Both Pomboy and Williams expressed surprise at the recent stock market rallies, as neither believes we have yet seen the worst. Pomboy said she was struck by the widespread expectations for a so-called V-shaped recovery in which, after a terrible Q1 and Q2, the economy roars back to life and a bull market resumes.

Said Pomboy,

"the idea that we are going to bounce out of this and go right back to where we were before just seems absolutely ludicrous to me."

The Inexorable Behavioral Changes

Pomboy sees several changes in behavior that will preclude a return to the bull market mentality at any time in the foreseeable future.

Those corporations that survive this catastrophe will emerge chastened about debt and will do all they can to keep leverage low. With a new appreciation for the fragility in global supply chains, they also will alter some of their business models, resulting in an unwind of much of the globalization that has occurred in the past two decades.

In a related vein, policy leaders will question the wisdom of the U.S.'s reliance on China for many products, starting with pharmaceuticals (or key pharmaceutical ingredients) and proceeding from there.

There also will be a change in individual behavior. Pomboy noted that after the Great Financial Crisis, U.S. households, which had been punished by high levels of personal debt and seen their investments shrink in the market collapse, began saving more out of after-tax income. That higher rate of savings persisted throughout the bull market despite the steady ascent in the values of the consumers' homes and retirement accounts.

Pomboy believes the economic dislocation from this latest and most sweeping economic shutdown will reignite the desire among consumers to increase their savings.

With corporations and consumers suddenly becoming parsimonious in their behavior, the U.S. government will become "the marginal spender of last resort" and the Fed will become the "marginal lender of last resort."

Government Will Become (Even) More Profligate

Actually, and Pomboy hints at this several times, we already are there. The U.S. government has already become the marginal spender of last resort, financed by the Fed playing the role of marginal lender of last resort. The initial $2.3 trillion "stimulus" package is destined to grow ever larger as the Democrats and Republicans discover they were always on the same page after all.

I recall from my youth how many gasped that, under Reagan, the federal deficit ballooned to 2.7% of GDP. The percentage last year was close to 5%.

And 5% will very soon seem impossibly modest. Pomboy believes we will see a deficit of between 20% and 25% of GDP this year. That equates, dear reader, to approximately $5 trillion of deficit spending. A number too large to grasp. With, of course, full-throated support from most of both political parties, and the signature on the spending bills from President Trump.

The received wisdom is that the stratospheric deficit will be but temporary, and that once the recovery (confidently expected to be V-shaped) is in full swing, deficits will quickly shrink to former levels.

Pomboy, though, is dubious, both about the shape of the recovery (which she believes will be more slow and painful than anticipated) and the behavior of the legislators. As she wrote in her April 7 analysis, having savored the taste of spending taxpayer money in a $5 trillion deficit confection, "our porcine politicos in DC will never go back to single-trillion peanut butter and jelly."

The Pension Crisis

The Pension Crisis

There certainly will be plenty of governors and mayors urging the porcine politicos to maintain their caviar spending diet. The great pension crisis, about which many (including Pomboy) have sounded clear warnings for at least the past decade, is well and truly upon us, and the cri de coeur from the states and municipalities will be for pension fund bailouts.

The pension funds have been among the chief victims of the interest rate suppression engineered by central banks.

With investment grade fixed income no longer adequate to generate the necessary returns, pension managers have increasingly looked for yield in all the wrong places.

With investment grade fixed income no longer adequate to generate the necessary returns, pension managers have increasingly looked for yield in all the wrong places.

These pensions have had to take an enormous amount of risk. They were the marginal buyers of all of the most toxic paper out there. You know, "Levered loans with no covenants? Sure, we'll take some of those! Investments in unicorn stocks through private equity that have no business and managed to lose a billion dollars a month? Sign us up for that!"

The U.S. had $5.3 trillion in unfunded public and private pension liabilities at the end of 2019.

That was, of course, before the coronavirus shut down large parts of the economy and caused asset values to plummet.

The pension crisis will rapidly become more acute for two reasons. First, even though the data won't be available for some weeks to come, Pomboy believes market losses from the coronavirus dislocation already have increased the already severe underfunding by several trillion dollars.

She sees the total unfunded pension liability rising this year to as much as $10 trillion, with most of that at the state and local level where money printing and deficit spending are not possible.

She sees the total unfunded pension liability rising this year to as much as $10 trillion, with most of that at the state and local level where money printing and deficit spending are not possible.

Second, with tax revenues certain to fall far short of forecasts made only a few months ago, state and local governments will strain to meet essential services and will have less money to fund pensions.

The problem is here.

Financial engineering tricks will no longer suffice to disguise it.

The only "silver lining," said Pomboy (making clear it is not a good thing at all), is that people, seeing the destruction of both their income and their savings, will be compelled to remain in the work force longer.

Some Wall Street Strategists Have Had It All Wrong

Pomboy has long been critical of those urging (with what she describes as an almost Pavlovian response) that higher deficits will mean higher interest rates.

She presented a chart showing just the opposite: The decline of the 10-year Treasury rate has occurred alongside a corresponding ascent of the Federal deficit as a percentage of GDP (and the inverse relationship held between 1960 and 1980, when Treasury rates rose as deficit spending fell).

She presented a chart showing just the opposite: The decline of the 10-year Treasury rate has occurred alongside a corresponding ascent of the Federal deficit as a percentage of GDP (and the inverse relationship held between 1960 and 1980, when Treasury rates rose as deficit spending fell).

Why should that be?

Pomboy cites two reasons:

First, the government typically borrows more when the economy is in trouble, so the backdrop for borrowing is not conducive to inflation.

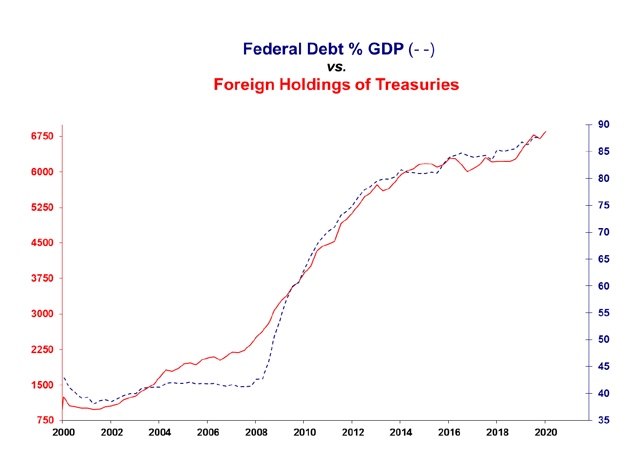

Second, for the past several decades, the rise of globalization has recycled U.S. dollars into the hands of foreign lenders, who in turn used them to buy U.S. Treasuries, thus tamping down rates.

Pomboy cites two reasons:

First, the government typically borrows more when the economy is in trouble, so the backdrop for borrowing is not conducive to inflation.

Second, for the past several decades, the rise of globalization has recycled U.S. dollars into the hands of foreign lenders, who in turn used them to buy U.S. Treasuries, thus tamping down rates.

In the interview, Pomboy noted how the financial system was unable to abide the rise in the 10-year rate to 3%, or even 2.5%, from several months ago.

Some part of the economy would run into trouble, the pressure for further rate cuts would build, and the Fed would cut in rapid order.

Some part of the economy would run into trouble, the pressure for further rate cuts would build, and the Fed would cut in rapid order.

This is not to say that there was no price to pay for what Pomboy calls our "policy sins." There has indeed been penance to perform, but it has been performed by the U.S. dollar rather than interest rates.

While foreigners were purchasing massive amounts of U.S. paper, the dollar declined as debt and deficits rose.

While foreigners were purchasing massive amounts of U.S. paper, the dollar declined as debt and deficits rose.

Another Pomboy chart, showing how closely the Federal deficit has tracked the trade-weighted dollar, nicely illustrates her point that "the dollar has become the valve for this angst, as it were, over our profligate fiscal policies."

The Vendor-Financing of our Profligate Spending

The Vendor-Financing of our Profligate Spending

Why has the U.S. been able to run hefty deficits for the past several decades? Pomboy's answer is the fulcrum to her entire world view:

The U.S. has been able to run those deficits because large parts of the rest of the world have been willing to buy our paper to, in effect, vendor-finance the export of their own goods.

In other words, because they were selling goods to us, buying our debt inured to the benefit of the exporting nations. It was seller financing, even if we didn't realize it. And that relationship carried us a long way.

Pomboy illustrates this with a remarkable chart on which foreign holdings of U.S. Treasuries are plotted against U.S. debt as a percentage of GDP:

As Pomboy observed, it's difficult to tell the two lines apart.

But Now, Change Is In The Air

So, why will that not continue? Why will the rest of the world cease to vendor-finance their exports to the U.S., soaking up Treasuries in the process?

Pomboy believes it will not continue because, for a host of complex reasons, the era of globalization is coming to an end. The nationalistic trends already evident with Trump's election in 2016 are receiving a powerful new impetus from the coronavirus crisis.

The behavioral changes outlined earlier, in which both corporations and households dramatically trim their spending and have a heightened reluctance to rely on foreign (especially Chinese) supply chains, mean there will be fewer exports for the foreigners to vendor finance.

The behavioral changes outlined earlier, in which both corporations and households dramatically trim their spending and have a heightened reluctance to rely on foreign (especially Chinese) supply chains, mean there will be fewer exports for the foreigners to vendor finance.

With the changes to corporate and household behavior, and the government as the marginal spender of last resort, the credit proposition for those who would consider buying U.S. debt is not compelling.

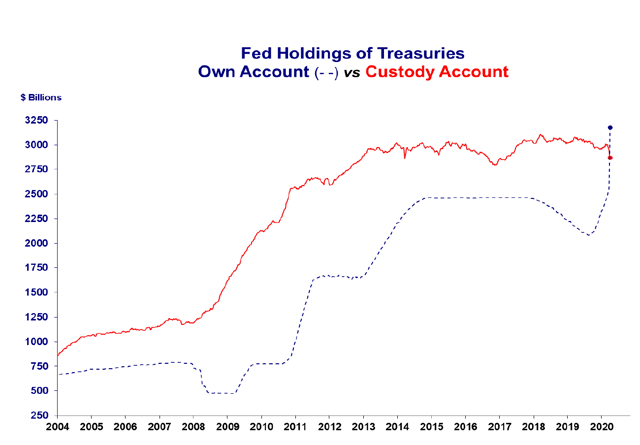

Consequently, Pomboy expects the demand for our federal debt to shrink. Indeed, it already has begun to shrink. This is evident from another stunning Pomboy chart, plotting the amount of Treasury securities on the Fed's balance sheet (in other words, bought by the Fed for its own account) over time vs. the amount held in the Fed's custody accounts (that is, held by the Fed for foreign government purchasers):

What just happened, earlier this month, to cause those lines to cross? For the first time, the Fed's holdings eclipsed the foreign holdings in the Fed's custody account as the Fed kept adding to its purchases while foreign central banks unloaded some $131 billion of their own Treasuries.

Pomboy sees this historical divergence as only continuing to grow. She does hold open the possibility that divestment of Treasuries by foreign central banks may have been temporary, prompted by a "dollar shortage" that will be cured by the Fed's unlimited swap lines and oil prices finding a bottom (thus putting more petrodollars into circulation).

However, she sees no chance that foreign purchases of Federal debt can keep pace with the immense amounts of Treasury purchases she anticipates the Fed will continue making. Indeed, she expects the Fed's balance sheet will grow to double digits (in trillions of dollars).

Will households and corporations, determined to save more and consume less, step into the breach as purchasers of U.S. Treasury paper? "Maybe that will be the great surprise," said Pomboy. Both she and Williams, though, expressed skepticism it would happen.

Who Will Buy Our Debt?

Who Will Buy Our Debt?

What happens now?

As foreign purchases of U.S. paper fail to keep pace with additions to the Fed's balance sheet, will the floor fall out from beneath the dollar?

As foreign purchases of U.S. paper fail to keep pace with additions to the Fed's balance sheet, will the floor fall out from beneath the dollar?

Pomboy offers the answer from the dollar bulls: the dollar won't decline so long as central banks in the rest of the world are also printing money as fast as they can to support their own domestic stimulus programs.

But that means we will see "the whole world printing money in unprecedented and unlimited fashion to support their economies." How does that finally end?

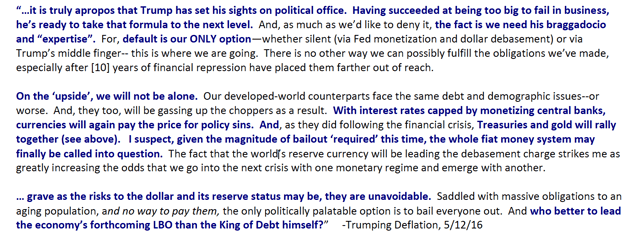

Pomboy (and Williams is in accord) dare to think the unthinkable: The hypertrophy of government spending and hyperactivity of central banks could soon spell the end of the fiat money system, which was inaugurated here when the U.S. untethered the dollar from gold in the 1960s.

From the interview:

From the interview:

Serious people are going to start to discuss: "How are we going to work our way out of this and how are all the developed world economies going to grapple with the massive amount of debt that they're facing?"

I again come back to the idea that the only way that aging, demographically-challenged, highly-indebted developed world economies can get out of this is to print money like crazy, because deflation is not an option for them. They have to inflate away the burden of this debt.

But if we all do it at the same time, and we have this race to the bottom, at some point the creditors, which are really China and other EM (emerging market) nations, are going to say, "Look, we're not schmucks. We see what you're doing over there. We're not having it."

Add to this the growing skepticism about whether China is truly a friendly nation, and whether we should be outsourcing much if any of our production there, and what we will see, believes Pomboy, is a debate between the developed world debtors and the emerging world creditors that comes to the center.

All Roads Lead To Gold

Who will want to buy our debt? With the benefit of vendor-financing removed, and with the explosion in money printing evident, no sensible creditor will. Unless, that is, the creditor can be assured that the U.S. dollar, in which loans are made and repaid, is somehow subjected to a discipline that will rein in the danger of inflation.

Ultimately, this business of currency is a confidence game. If the creditor lacks confidence that your currency will retain value when time for repayment comes, it will not agree to make the loan in the first instance. How does a creditor protect itself? By demanding repayment in something solid. Something real.

[I]t's going to have to come back to a hard asset tether, going back to a gold standard or something along those lines.

Pomboy noted in her recent research piece that the U.S. may have one significant advantage none of the other deeply indebted nations has: a huge gold reserve.

Should the de facto embrace of overt monetary finance (aka unlimited money printing) around the globe call into question the whole fiat money system, and we go back to a hard-money tether via a gold standard, the fact that the US has the largest gold reserve of any country gives us great advantage.

Yes, both Pomboy and Williams are advocates of a gold standard, or something similar. This is different from the attachment to gold cherished by those who value its concentrated value or portability, and who might perhaps imagine slipping a gold coin to a border guard in a time of great unrest, or exchanging bullion for produce in a time of famine.

Pomboy and Williams are attracted to gold because they believe that, for all its faults as an anchor of currency, it is the least faulty solution out there, and far preferable to the place where fiat money ineluctably leads.

In Pomboy's recent piece, one of the "Trump Cards" from the title was the notion that our President might require China to pay for the coronavirus by forgiving the trillion dollars or so that we owe its central bank.

But even if it doesn't come to that (which it probably won't since the $1t we owe China is a drop in our rapidly expanding bucket of borrowing) the US still has a trump card it can play in the new world order. And this one is also one of the President's legendary affections. No. I'm not talking about exotic models. I'm talking about gold.

Should the de facto embrace of overt monetary finance (aka unlimited money printing) around the globe call into question the whole fiat money system, and we go back to a hard-money tether via a gold standard, the fact that the US has the largest gold reserve of any country gives us great advantage.

Pomboy said that if the idea of Trump reverting to the gold standard sounded familiar,

it was because she had written about it six months before the 2016 Presidential election:

I'm stunned by the prescience of that passage, all the more prescient because written at a time when it seemed inconceivable to most (certainly to me) that Trump could be elected.

Investment Implications

Am I persuaded by the arguments of Pomboy and Williams? I'm certainly taking them seriously. I have a small amount of gold in my own portfolio, and am wondering whether it would be wise to add more.

Anyone intrigued by the thinking of Pomboy and Williams might consider several actions.

First, a subscription to Things That Make You Go Hmmm and to the work of MacroMavens.

Both may be among the most valuable investments you ever make.

Second, a careful consideration of what types of investments are likely to hold value in a time of high inflation and, as importantly, what types of investments are especially vulnerable to inflation.

Third, a careful consideration of whether gold should be a part of one's investment portfolio.

There are several ways to invest in gold.

They include:

- Purchasing the physical asset, though that presents custody and storage issues;

- Investing in gold mining companies, such as Barrick Gold (NYSE:GOLD) and Kirkland Lake Gold (NYSE:KL);

- Buying mutual funds focused on companies engaged in the exploration, mining, or processing of gold;

- Purchasing shares of a fund that replicates the price of gold, such as SPDR Gold Shares (NYSEARCA:GLD); and

- Trading gold futures and options in the commodities market.

It's beyond the scope of this article to recommend any of these types of investments. Rather, my intent is simply to introduce the reader to the big picture thinking of Stephanie Pomboy and Grant Williams, and to suggest such thinking is ever more important in this, the most uncertain economic era of our lifetimes.

A Short Word About Tesla

A Short Word About Tesla

Adam Jonas of Morgan Stanley was out with a note today (I'm writing this on April 15), which included the following passage:

4. Extraordinarily high trading volume. At the risk of reading too much into technical factors, we do pay attention to the extremely high levels of volume traded in Tesla shares. For example, the value of shares traded yesterday (4/14/20) was close to $22bn.

On the same day, Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL) traded $14bn of value and Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN) traded less than $19bn of value.

Our own efforts to investigate exactly where the volume comes from (retail, institutional, index, quant, options/vol hedging, etc.) have proven to be in many ways opaque and, frankly, inconclusive. It seems to us that, to a degree, the trading of Tesla shares has been driven by factors that go beyond the fundamentals influencing an electric car or even a technology company.

If Adam Jonas is mystified by what's going on with the trading of TSLA, do you imagine this is any time for you to be considering initiating or adding to a short position? I certainly don't.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario