The unprecedented nature of today’s economic shutdowns make it hard for lenders to update the complex models at the core of their business

By Rochelle Toplensky

Unprecedented is an overused word of late, but it does precisely capture a key challenge for banks:

How to update the models at the heart of their businesses, given widespread economic uncertainty and a dearth of relevant historical data.

Major U.S. and British banks are preparing for loan losses. / Photo: ben stansall/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images .

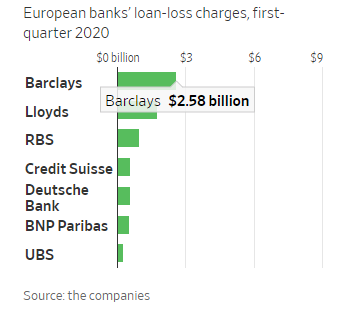

In recent first-quarter results, lenders used widely differing approaches and assumptions about the coming months to estimate loan losses. The only consensus: It is still too early to know how this crisis will play out.

That is understandable, given how little clarity there is about the path to recovery, with expectations shifting almost daily. But it also increases the risk that those complicated models get it wrong, with real-world consequences for investors.

Models—used not just to estimate loan losses but also to value little-traded assets and design, price and assess the risk of products—are crucial to a bank’s financial position and health. U.S. and European banks have relatively strong balance sheets and buffers for now, but they are still giant leverage machines, carefully calibrating their risks and capital levels to boost returns.

Depending on how they are calculated, estimated loan losses or asset revaluations could easily eat into those buffers.

Loan-loss estimates in particular are sizable and uncertain. The six largest U.S. lenders set aside over $25 billion for loan losses in recent results, which seems little more than a first guess and will likely rise.

Major British banks estimated their losses at £7.5 billion ($9.2 billion) in the first quarter, but the full year hit could be as much as £18.5 billion, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence.

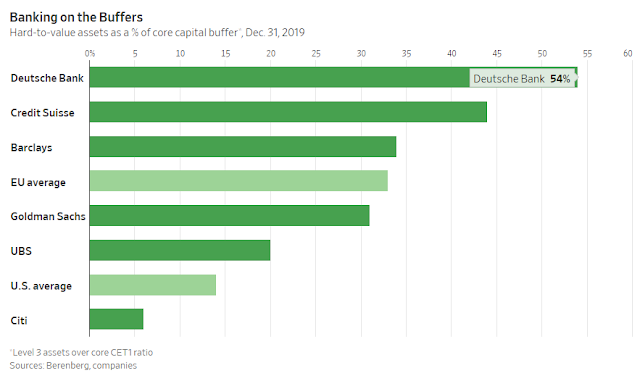

Banks also routinely revalue their financial instruments, and those that aren’t widely traded—so called Level 3 assets—are priced using internal estimates. The big U.S. and European banks have reduced their Level 3 holdings by 27% in the past five years, according to brokerage Berenberg, but some, particularly in Europe, still have a lot of these opaque assets on their books relative to their capital buffers.

Lenders have an army of boffins with Ph.D.s and advanced modeling skills on hand to help.

They also have decades of market data, including for the 2008 global financial crisis. The big problem is that there is no useful paradigm for the current pandemic-caused crisis, particularly with its global scope and risk of additional waves and lockdowns. It has ushered in extreme movements in markets and levels of government spending that just a few months ago would have seemed absurd. It is very hard to know what will come next.

Models can be stretched with extreme scenarios to check their sensitivity, and results can be adjusted for factors not captured in calculations based on historical data. Novel new information sources, such as traffic or mobile phone data, are being tested. But the updates are inevitably based on a mix of science and art with a sprinkling of guesswork.

In the circumstances, it is little comfort that the models are independently tested by banking regulators and external auditors. Official oversight is subject to the same uncertainties as the modeling process itself.

The current crisis has made the imperfections and risks inherent in bank models a lot worse, and miscalculations could be expensive. The coming quarters could spring a few surprises on bank investors.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario