By: Caroline D. Rose

For nearly three years, since the 2016 oil market crash and the U.S. shale boom, Russia and Saudi Arabia worked together to stabilize global oil prices as part of the OPEC+ alliance. But it seems this partnership is now on the brink of collapse.

As the coronavirus pandemic threatens to shutter businesses, ground airlines and put a massive dent in consumer spending, demand for fuel has sharply declined – especially with the world’s top oil importer, China, being among the countries most affected by the outbreak early on.

With a vaccine for COVID-19 at least a year away, there are few signs that demand will recover any time soon. Earlier this month, OPEC members urged producers to curb output, but one country refused to toe the line.

Russia resisted OPEC’s call to cut production by 1 million barrels per day, hoping instead to take advantage of other producers’ willingness to do so. In response, Saudi Arabia has deployed a strategy of brinkmanship, announcing that it would increase output by 2.5 million bpd in April to drive prices down and force Russia into compliance.

The Saudi strategy is twofold. It’s attempting to lower prices to attract customers who are willing to stockpile supplies. At the same time, it’s hoping low prices will squeeze Russian finances and force Moscow to surrender to OPEC demands. But this strategy will come at a high cost to the Saudis.

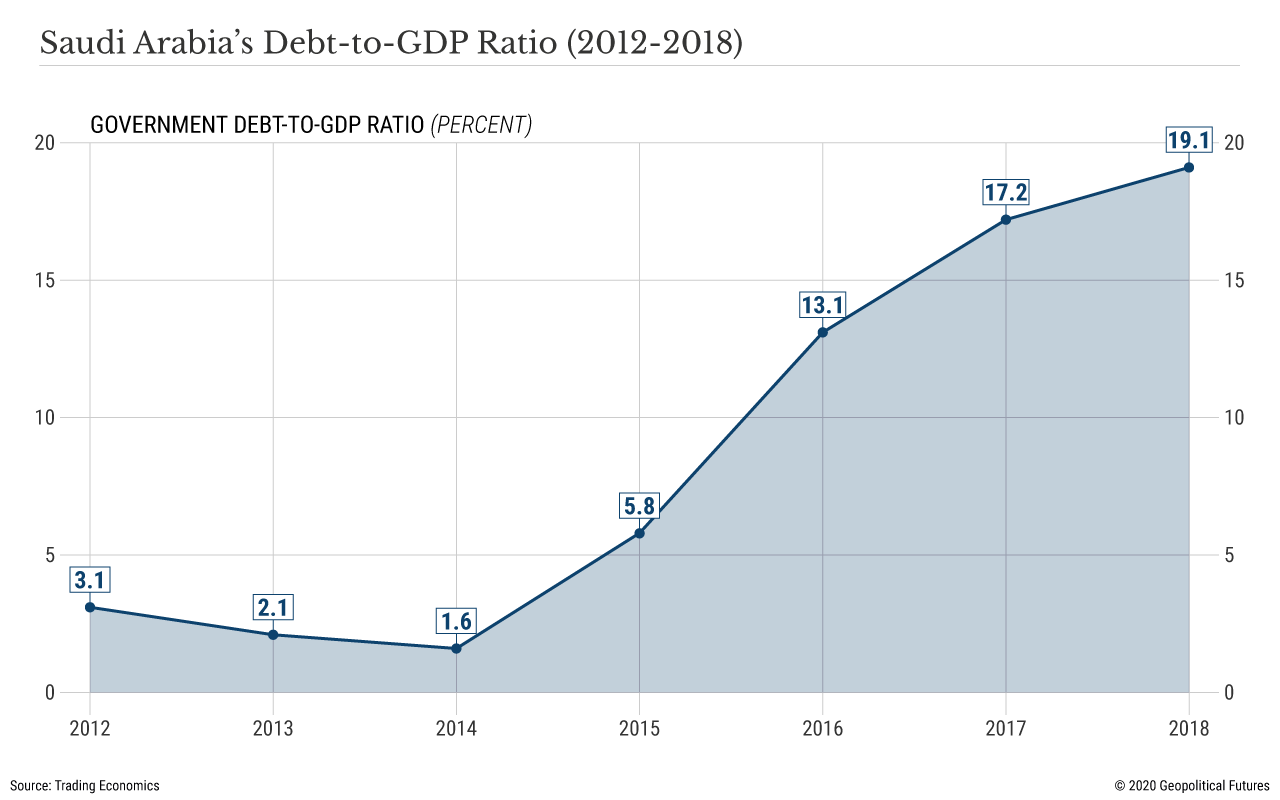

It is forcing Riyadh to draw more from its sovereign wealth fund than it had previously intended, drying up funds that it hoped to use to support its engagements abroad and to diversify its economy.

The coronavirus crisis has highlighted countries’ prioritization of national interests over the collective, and the oil price war is no different. Russia and Saudi Arabia have raised the stakes to generate revenue, increase market shares and compete for dominance in the global oil market.

Can Saudi Arabia Keep Up?

The Saudi government has indicated that it is in a race to increase pressure on the Kremlin, cranking up production to nearly five times that of Russian crude output. But can it play the long game, balancing its budget at a lower price than Russia can?

From its perspective, getting Russia to capitulate is a long-term objective, and one worth incurring revenue losses in the short term, because it will demonstrate that the Saudis really call the shots for OPEC+ members. Saudi Arabia believes its ability to produce oil cheaper than Russia ($8.98 per barrel compared to $19.21 for Russia) and larger global market share give it an advantage.

In reality, however, Riyadh may be forced to yield before Moscow. Saudi Arabia needs oil prices at $91 per barrel – more than three times the current price – to balance its 2020 budget. In contrast, Russia’s 2020 budget is based on oil priced at $42.40 per barrel, meaning that it can actually tolerate low prices for longer than the Saudis.

Currently, Brent crude is at $28.70 per barrel, while Saudi Light is priced at $26.54. Some experts have predicted that prices could plummet even further to just $10 per barrel, as businesses big and small feel the fallout of the coronavirus crisis. Some observers believe the low prices could lead to a 2-4 percent decline in Saudi Arabia’s gross domestic product.

Even with the country’s reserves – some of the largest in the world, with assets worth $320 billion – current prices are unsustainable, particularly given that the crisis could last eight months to a year. True, this isn’t Riyadh’s first time facing a crash in oil prices; it has managed to manipulate the market to its advantage during other times of crisis. During the oil surplus in the 1980s, it reduced its own production to try to keep prices high.

It also manipulated the market in 2014 to counteract the U.S. shale boom. But in the current environment, increasing demand will be far more difficult, especially as the pandemic and an oncoming recession paralyze importers and sectors dependent on fuel. Even stimulus packages worth billions of dollars may not be enough to produce a surge in energy demand. They may help keep some companies and industries afloat, but they likely won’t produce an immediate and prolonged spike in oil sales.

In addition, Russia’s energy sector is showing no sign of slowing down. In fact, the country has increased its output by 500,000 bpd – half of Saudi Arabia’s own increased output – proving it can weather the storm. Furthermore, the Kremlin said it had enough cash to get through six to 10 years of oil prices between $25 to $30 per barrel. Russia will take a hit, of course, but in the long term its outlook is more optimistic than Saudi Arabia’s.

Domestic Considerations

Even before OPEC+ negotiations collapsed, Riyadh anticipated declining demand. The Saudi Finance Ministry asked government agencies to cut spending by 20-30 percent at the beginning of March in anticipation of a crash in prices. Now, with the coronavirus pandemic and the ongoing price war, Saudi Arabia has pumped the brakes even harder on spending.

Last week, the government announced it would slash its 2020 budget by 5 percent, or 50 billion riyals ($13.2 billion). The government said the cuts would have no socio-economic impact, but the reality is that most of the cut funds were intended for projects in its non-oil sector.

As oil demand wanes further and prices fall, Riyadh will have to draw more money from its Sovereign Wealth Fund than it originally intended – funds that were meant to support long-term objectives, like its involvement in Yemen’s civil war, countering Iran’s expansion in the Middle East and diversifying its economy.

Despite reduced spending, Saudi Arabia is still looking at a $61 billion deficit for this year, according to some experts, as revenue falls short of the government’s 2020 projection ($210 billion) and spending hovers around $270 billion. And the country is simultaneously facing another challenge: domestic control.

Over the past few weeks, members of the royal family and activists alike have criticized Riyadh’s management of the coronavirus crisis, despite the fact that Saudi Arabia has not been hit as hard by the outbreak as many other countries, registering about 1,000 confirmed cases so far.

The government’s decision to suspend prayer at mosques in Mecca and Medina, Islam’s two holiest cities, has undermined its credibility as the guardian of the Islamic faith and sparked concerns in the Islamic community that the coronavirus threat will continue well into the summer and force the government to shut down the hajj pilgrimage, which is set to take place in July and August.

This, too, carries serious economic consequences; the hajj brings 2.5 million visitors to Saudi Arabia every year and just over $12 billion in revenue, accounting for about 20 percent of the country’s non-oil economy.

Though the royal family still has a strong grip on power, public frustration with low oil prices could test the Saudi leadership. Approximately 20 percent of the country’s population holds shares in Saudi Aramco, so low oil prices resulting in part from Riyadh’s efforts to force Russia to capitulate could lead to widespread anger – even dissent. This could intensify if a recession emerges in Saudi Arabia, where unemployment has been high since 2015, reaching roughly 12 percent at the end of 2019.

Most important, the price war will put at risk Saudi Arabia’s most vital domestic objective of the first quarter of the century: reducing its dependence on oil through the Vision 2030 campaign. In 2016, the country promised it would be able to “live without oil” by 2020. But 2020 has arrived and Saudi Arabia remains reliant on energy – even more so now that the price war is chipping away at funds intended for investment in non-oil industries.

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has touted Vision 2030 as a strategy to diversify the economy, bolster the private sector, increase social spending and reduce unemployment to 7 percent. But Vision 2030 has been hampered by declining oil prices and has struggled to attract foreign investment. The current price war will only exacerbate these problems.

Both Russia and Saudi Arabia acknowledge that this game cannot last; one or the other will succumb to the fiscal pressure and slow down production. Neither country wants to be the first to do so, however. For MBS, the pressure to mitigate the ripple effects of low prices while also keeping the heat on Russia is mounting. Winning the price war is critical to Saudi Arabia’s credibility, both at home and abroad.

Geopolitical Outcomes

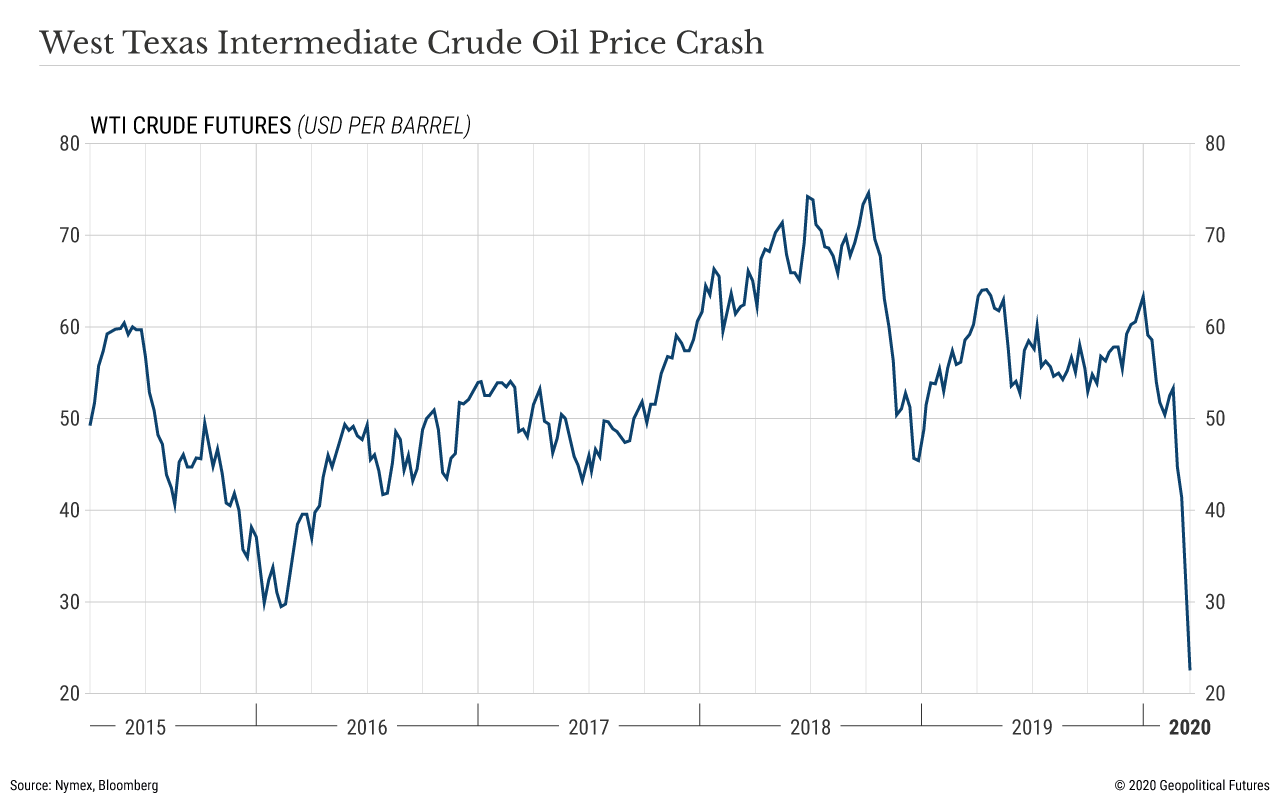

As the gap between Moscow and Riyadh widens, there have been broader effects on the oil market and other producers. One of the unintended victims of the price war has been the U.S. shale industry. Producers have already begun to slash spending, prevent share buybacks, furlough employees and announce service discounts to stay afloat. By the beginning of this week, WTI shed 60 percent of the value it had accumulated since the start of this year.

There is now talk of a wave of bankruptcies as debt accumulates and write-downs skyrocket.

Regulators in Texas are beginning to consider curbing production – for the first time in 50 years.

But new opportunities have also opened up. The U.S. has tried to convince Saudi Arabia to ease up and even publicly acknowledged the possibility of a U.S.-Saudi oil alliance. That acknowledgment came after reports that some U.S. energy officials were interested in establishing an agreement with the Saudis to stabilize prices. Such an alliance would inevitably act as a counterbalance to Russia’s oil industry.

Washington already appears to be making attempts to align closer with the Saudis. On Monday, the U.S. fast-tracked the appointment of Victoria Coates as a special energy representative to Saudi Arabia. The U.S. also announced plans to dispatch Coates to Riyadh for the next few months for negotiations with Riyadh. There has also been talk of the U.S. potentially arranging a meeting with Saudi leaders to convince Riyadh to match cuts made by the United States.

As it stands, the road to recovery is long. Saudi Arabia, unable to set prices or increase demand, is running out of options and adopting a series of risky moves, hoping that it can either force Russia to capitulate or find new partners with which to navigate the oil market.

OPEC+ as a price control regime is fragmenting, and Saudi Arabia is increasingly unable to sustain its pressure campaign on the Russian energy industry. And as the coronavirus crisis intensifies and a global recession looms, it will become even more difficult for the Saudis to coerce the Russians into compliance.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario