By: Allison Fedirka

Known for his contrarian and uncouth behavior, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro frequently comes under intense scrutiny for his decisions. The latest controversy stems from his refusal to shut down economic activity in response to the coronavirus outbreak. Many governments face this decision but few have opted for Bolsonaro’s economy-first approach.

The policy hasn’t been well received at home: Governors have lined up against him, media outlets have raised the idea of removing him from office, and even Facebook removed a video of Bolsonaro speaking to street vendors on the grounds that the content violated misinformation standards related to the virus.

But however controversial it may be, there is a method to Bolsonaro’s apparent madness.

Brazil’s economy is simply too weak to deliberately close down for a prolonged period of time.

Backlash

Brazil first addressed the coronavirus as an economic problem rather than a public health one because the economic effects arrived a month before its first confirmed case. At the end of January, Brazilian mining giant Vale suspended operations in China and restricted travel to and from the country.

In early February the electronics industry, particularly makers of small electronics such as mobile phones, started experiencing supply chain problems, and by mid-month firms were implementing short-term closures and discussing furloughs. Leading solar power companies in Brazil, also highly dependent on China, forecast supply shortages in April and May as well as a 5-10 percent drop in sales.

Brazilian beef exports – worth billions of dollars when it comes to China trade – experienced a sharp drop in demand, putting small and medium-sized slaughterhouses in peril of closing.

Oil giant Petrobras, which sends 72 percent of its exports to China, also reported slumping demand. The shipping industry and exporters expressed worries about a potential shortage of containers by April. All this occurred before Feb. 25, when Brazil reported its first confirmed case of COVID-19.

Once the virus arrived in Brazil, the question in the government of balancing competing demands between health and economic needs unsurprisingly turned contentious. Bolsonaro leads the economy-first camp, downplaying health risks in public and rejecting restrictions on social movement on the grounds that they will destroy the economy. He advocates “vertical isolation,” which calls for the elderly and those with preexisting conditions to self-isolate while everyone else goes about business as usual.

On the public health side, several state governors, led by Sao Paulo’s Joao Doria and accompanied by Rio de Janeiro’s Wilson Witzel, have called for restrictions on movement for the whole population. Together, these two states account for nearly 40 percent of national gross domestic product and are home to 63.2 million of Brazil’s 210 million inhabitants. Restricting economic activity in these states will greatly reduce the country’s GDP.

On one hand, the governors fear that their densely populated major cities are conducive to the virus’ rapid spread. But on the other hand, those cities also have concentrations of poor neighborhoods whose residents cannot afford extended periods of limited or no work.

A further complication is the question of jurisdiction. In mid-March, the executive proposed legislation aimed at centralizing power to regulate the closure of businesses and social distancing measures to ensure an efficient response. The proposal now has 126 amendments and is currently in a joint commission for discussion, allowing governors to pursue their own measures in the meantime.

A second measure that addresses workers’ rights and unemployment during the crisis has already been rejected by some legislators as unconstitutional. Judges have weighed in, encouraging the federal government to coordinate efforts more closely with states.

Bolsonaro is reluctant to limit economic activity because the Brazilian economy is weak and can ill afford another economic crisis. Brazil has yet to recover from its two-year recession from 2015 to 2016. During that time, GDP contracted by nearly 7 percent. In the three years since, the economy essentially stagnated, registering growth of just about 1 percent annually.

Prior to the recession, in 2014, Brazil overtook the United Kingdom to become the seventh-largest economy in the world, with a GDP of $2.4 trillion. Now the economy ranks ninth globally, with a GDP of $1.89 trillion.

The unemployment rate in 2014 was 6.8 percent before doubling to 13.7 percent in early 2017.

Now unemployment has been reduced to 11.6 percent, though the quality of jobs created is low, as is remuneration.

Plans Interrupted

Bolsonaro was elected in 2018 on a pledge to reform and jump-start the economy, but economic measures taken early in his term have reduced the country’s arsenal for dealing with the impending global recession.

Last year, the government focused on structural reforms and facilitating household consumption, which accounts for over 70 percent of GDP. The central bank launched monetary easing in July 2019 in an effort to boost lending to consumers. In the second half of 2019, the government also permitted individuals to withdraw funds from their Workers’ Severance Fund accounts to help boost economic activity.

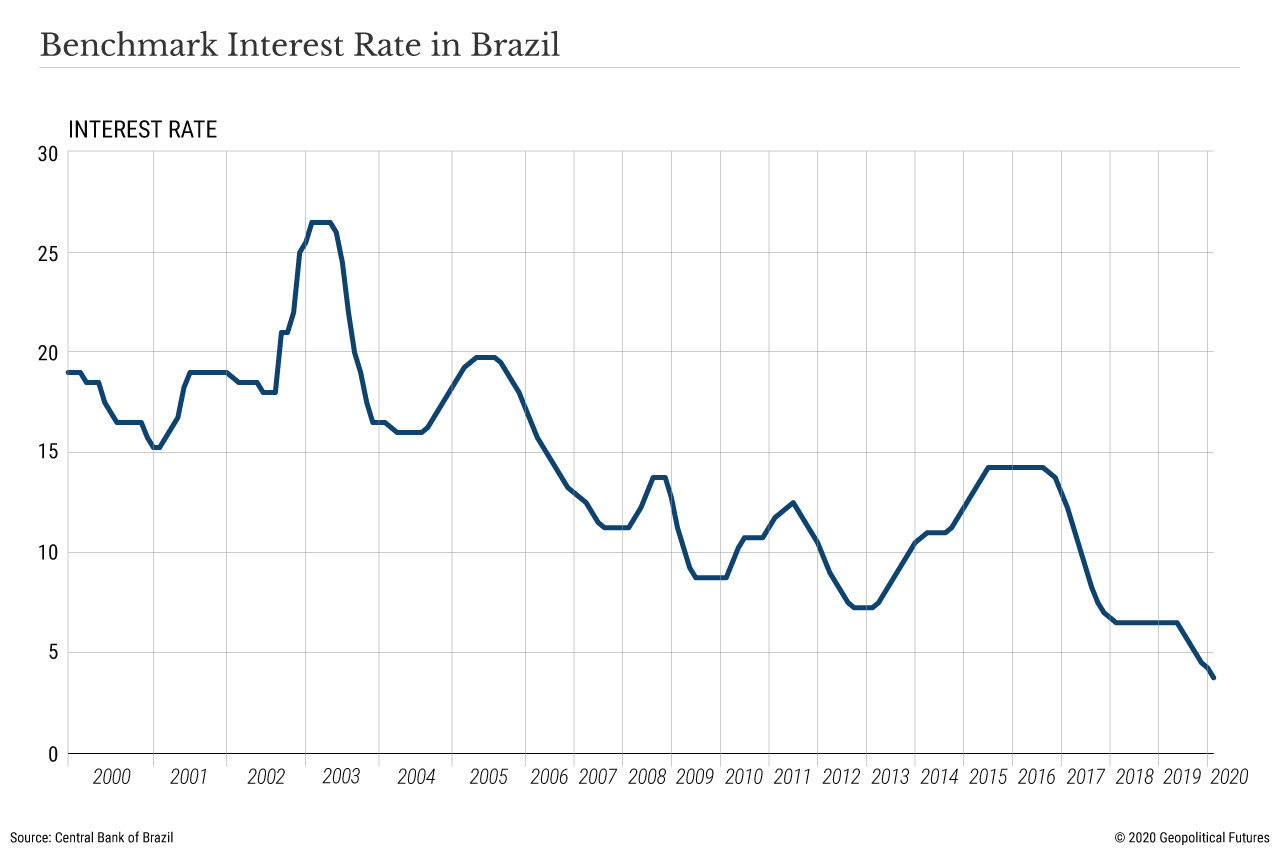

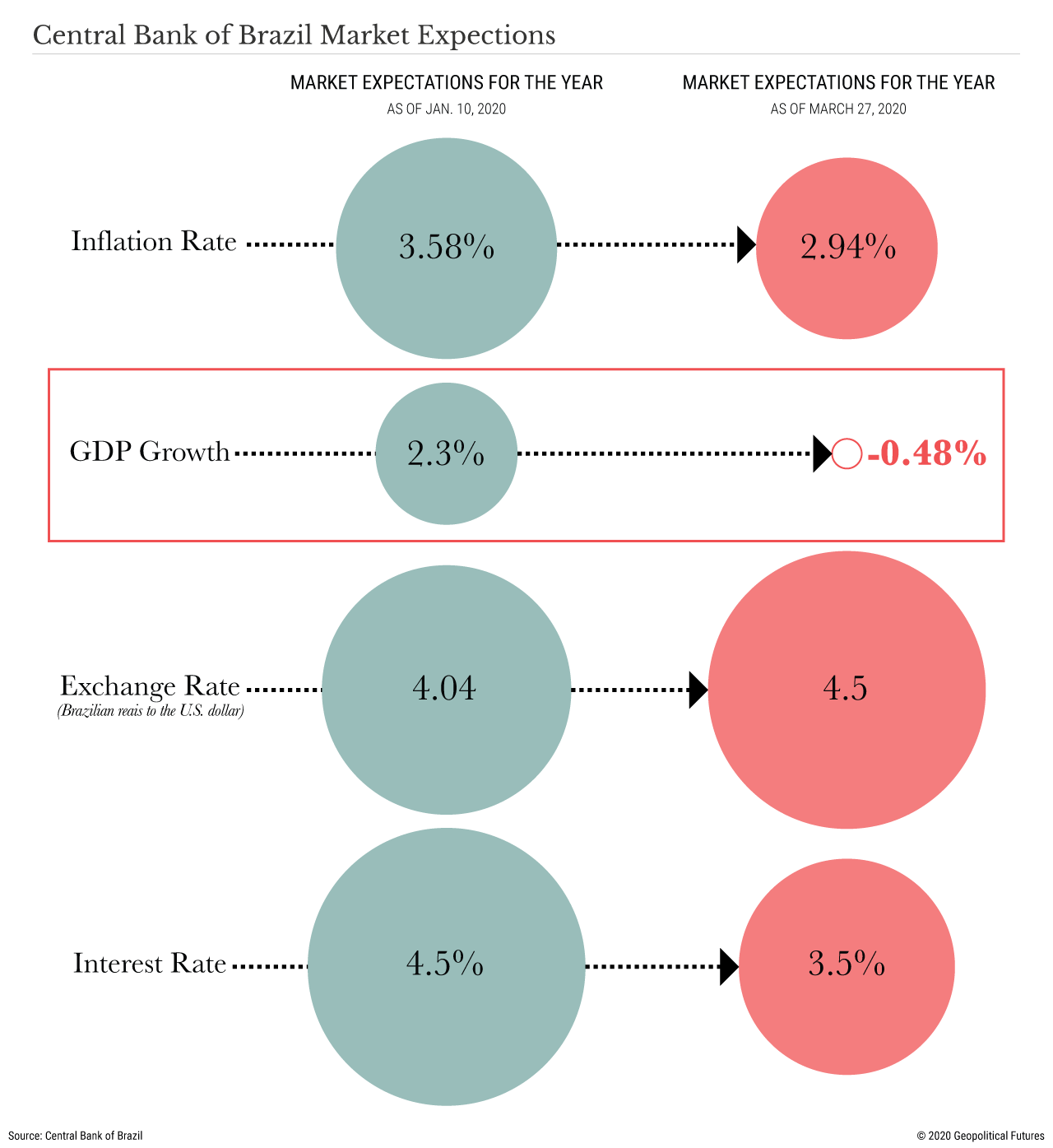

The effect of these policies was supposed to kick in during the first half of 2020, but the onset of the global recession doomed the strategy from the get-go. In just two months, the central bank cut interest rates to 3.75 percent from 4.5 percent. Though there is still room to go lower, these rates are already very low by Brazilian standards.

The global downturn has hampered other stimulus policies. A privatization drive was intended to raise 150 billion reais ($29 billion) this year, but this week the electric utilities company Eletrobras postponed its privatization plans until 2021, and others will likely follow.

The government also loosened rules to give foreign companies equal footing in competition for government contracts, with public tenders valued at 50 billion reais, but foreign investment interest has dried up. Finally, the government planned limited trade deals to open markets and diversification in trade with China, the U.S., Mexico and India. But trade has fallen off a cliff, and governments are focused on mitigating the contagion and economic damage at home.

Other plans to remake the economy have had to be repurposed to limit the short-term damage from the virus. A plan launched in February called Brazil More included funds to incentivize startups and provide more credit to small and medium-sized businesses, but it will now be used to save existing companies. Around the same time, after months of study, the central bank loosened reserve requirements in a move that could inject up to 135 billion reais into the economy.

The central bank will also allow individuals to use personal retirement plans as collateral to access lower interest loans.

And lastly, there are the reforms that risk being undone as a result of the government’s all-out effort to mitigate the impact of the recession. One of the main objectives of the reforms was to cap government spending and reduce debt.

However, in mid-March, it became apparent that government bailouts and other costly measures would be necessary to prop up the Brazilian economy. A state of emergency was declared, enabling the government to remove national spending caps and launch a 147.3 billion-real support package to ensure liquidity, prevent layoffs and support vulnerable groups.

The government also intended to reduce its support for states’ debt but has now released an

85.8 billion-real bailout package for them (and that’s after suspending debt payments).

At the end of 2019, the government stayed on track for a primary budget surplus of 1 percent of GDP, well below the official goal of 2.3 percent. The National Treasury now anticipates a primary deficit for 2020 of 4.5 percent of GDP (over 350 billion reais), well over the previous goal of 124.1 billion reais.

Difficult Choices Ahead

Support packages like these can keep firms afloat only for so long, and the ability to extend them depends on disposable resources. Herein lies the problem for Brazil: It has very limited headroom to deal with these matters. There are already concerns over the potential for a credit crisis and future lack of investment.

The government does have $359 billion in reserves, but it is extremely reluctant to tap these resources – the government would do so only if it believed it was entering the worst-case scenario. All of this is further complicated by the fact that dollar gains against the real since the start of this year resulted in a 43.4 billion-real increase in gross debt, and low oil prices have wiped out tens of billions of reais in oil-related royalties and tax revenue (the budget was based on an average price of oil of $61.25 per barrel).

Under these circumstances, Bolsonaro’s effort to preserve what’s left of Brazil’s economy at any cost does not seem unfounded. At present, the economic pause in parts of Brazil has been in place for only a couple of weeks.

During this time, the government has worked to better position the economy to stay afloat. The calls for vertical isolation demonstrate that the government believes it is reaching the limits of its ability to save the economy from severe recession if more economic activity is not restored soon.

Bolsonaro, of course, is not alone in being trapped between two bad policy options, and many leaders will soon have to decide when measures to protect public health no longer outweigh the economic cost.

When this shift will occur depends on the economic resilience of the country in question, and Brazil came in with a weak hand already half-played.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario