by: Lyn Alden Schwartzer

Summary

- Most of the Fed's liquidity operations, ultimately, are to support the U.S. treasury security market.

- The U.S. debtor nation status plays an important role in why the Fed is on the hook to provide foreigners with dollar liquidity.

- Keep an eye on international markets with positive net international investment positions; they could do well post-virus.

- The U.S. debtor nation status plays an important role in why the Fed is on the hook to provide foreigners with dollar liquidity.

- Keep an eye on international markets with positive net international investment positions; they could do well post-virus.

Over the past several weeks in response to the COVID-19-induced global economic shutdown, the U.S. Federal Reserve has announced an unprecedented number of operations to relieve or bail out various markets, as the lender of last resort.

Eric Basmajian provided a solid breakdown of the operations in place as of a couple of weeks ago, and that article is certainly worth a read. The Fed has expanded the monetary base to buy Treasuries and other securities at a record pace, has put in place various lending facilities, and has opened a record number of currency swap lines with other countries.

This article takes a look specifically at some of the Fed’s international operations to help readers understand why the rest of the world is currently the Fed’s problem. The short version is that most of what they are doing is ultimately to protect the U.S. Treasury market.

It’s The Debt, Not Just The Virus

Many analysts are focused on the impact of the virus itself, which is indeed very large. Nearly 10 million jobless claims were filed in the United States in the past two weeks due to the shutdown of restaurants, travel businesses, casinos, physical retail, and parts of several other industries, and that can’t be understated. Job losses are likely to continue as well.

However, the sheer speed of the market’s crash, and the unprecedented actions by the Federal Reserve and other central banks around the world to support the credit market, point to an even larger issue: we’re likely in the later stages of a global debt supercycle. The sheer amount of debt in the world makes temporary income disruptions a lot more financially impactful than they would be in a system with less leverage.

As of 2019, global debt surpassed $250 trillion, which is more than 250% of the world’s GDP.

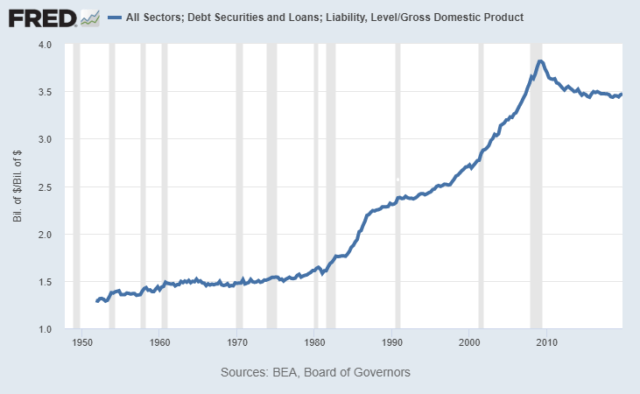

In the United States, our total debt (government, corporate, and household) is around 350% of GDP, which is the same ratio of debt that we had back in 2007 at the start of the previous financial crisis (although during the crisis, it ended up reaching as high as 380%):

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

We have less mortgage debt relative to GDP, but most other types of debt, especially sovereign debt, are higher as a percentage of GDP in 2020 than in 2007. We just re-arranged where the debt is concentrated, and pushed it up especially to the sovereign level.

The $40 Trillion Problem

The U.S. dollar is used around the world for purchasing commodities, settling a large portion of international trade, and providing financing for companies between nations. However, the usage of the dollar has exceeded the growth of the U.S. economy and U.S. money supply, which along with other factors has led to a global dollar shortage. This shortage becomes particularly acute during global economic slowdowns or recessions, such as in 2008, 2016, and 2020 when trade diminishes and commodity prices fall in dollar terms.

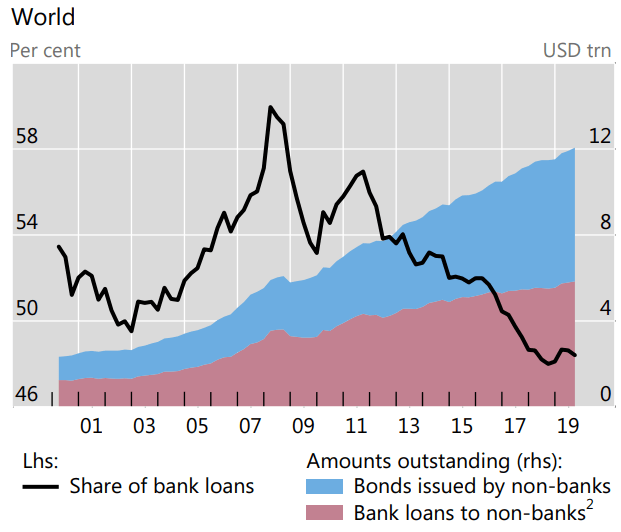

There is a lot of dollar-denominated debt held by institutions outside of the United States. The Bank for International Settlements estimates this figure at over $12 trillion. It’s much smaller than the amount of dollar-denominated debt within the United States, but can be just as problematic because dollars are more scarce outside of the United States.

And it’s worth noting that these $12+ trillion in dollar-denominated debts mostly aren’t owed to lenders in the United States; institutions in various countries lend to others in dollars.

When global trade slows down and commodity prices fall, the global dollar flows diminish from a roaring river to a small stream, so these dollar debts suddenly become a lot harder to service thanks to a scarcity of dollars outside of the United States relative to the size of these debts.

Here’s the BIS chart of ex-USA dollar-denominated debts:

Source: BIS

Back in 2008, when ex-USA dollar-denominated debts were about $5-$6 trillion and global trade slowed down, the Fed did currency swaps with several major ally central banks, to ensure they have adequate dollar liquidity to supply their institutions with.

In 2020, they’re doing currency swaps with the same countries, but also nine new ones including several emerging markets.

In addition, the Federal Reserve has an international repo operation, meaning that foreigners can lend their Treasuries to the Fed as collateral in exchange for dollars.

Many readers may be wondering, why is this the Fed’s problem?

Why does the United States need to provide dollar liquidity to the rest of the world, who have $12+ trillion in dollar-denominated debts and a shortage of dollars to service those debts? Why not just let it all burn down, i.e. let it all default, outside of the United States?

For sure, it’s not out of the kindness of the Fed’s heart.

Instead, it’s because the U.S. is a debtor nation, and providing dollars is required if the Fed wants to ensure stability in the U.S. Treasury market and the rest of the U.S. economy and capital markets.

As I described in my article about the Great Depression, after World War I, the United States became the world’s largest creditor nation, meaning that Americans owned more foreign assets than foreigners owned of American assets.

However, due to persistent trade deficits as the world reserve currency (meaning more wealth flows out of the country each year than into the country), we lost creditor status and entered debtor status starting in the 1980s, meaning that foreigners now own more American assets than Americans own of foreign assets.

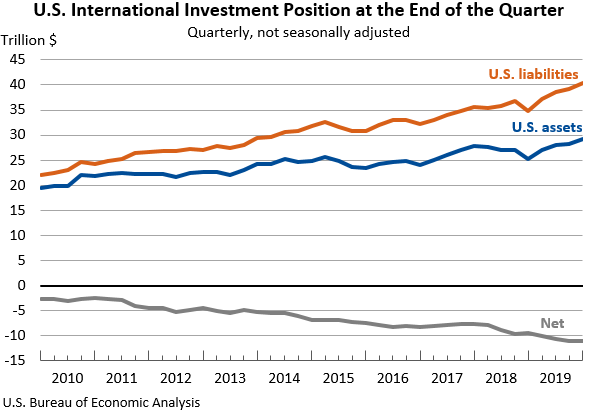

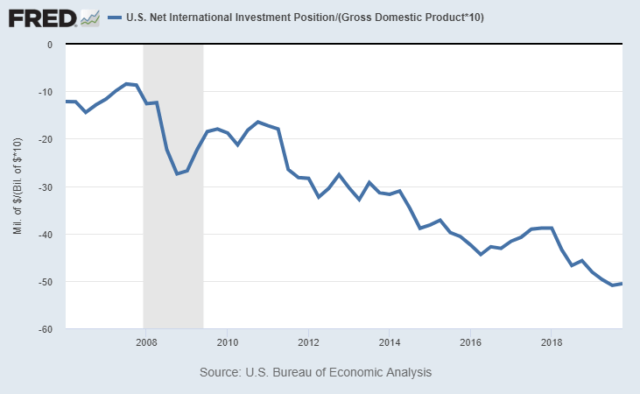

When the 2007/2008 financial crisis began, the U.S. net international investment position was equal to about -10% of U.S. GDP. It has worsened significantly since then in just those 12 years, and is now about -50% of U.S. GDP.

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

Specifically, foreigners own $40 trillion in U.S. assets, including portions of our government debt, corporate debt, stocks, and real estate. Americans own just $29 trillion in foreign assets.

So, we have a negative $11 trillion net international investment position (NIIP deficit) with the rest of the world, which equals about -50% of our $22 trillion GDP.

Chart Source: U.S. BEA

Today, Japan is the world’s largest creditor nation, meaning that they have the largest absolute positive NIIP. This means that the gap between the amount of foreign assets they own vs. the amount of Japanese assets foreigners own is larger in absolute terms than any other country.

Germany, China, Taiwan, Switzerland, Norway, Singapore, and Saudi Arabia are also high on the list of creditor nations in absolute terms.

The United States is the world’s largest debtor nation, meaning we have the most negative absolute NIIP. We’re the world’s worst in absolute dollar terms, and one of the low ones in terms of NIIP as a percentage of GDP, although several countries like Ireland and Spain are worse in those relative-to-GDP terms, so we’re not at the very bottom in that sense.

The reason why this matters, is that foreigners have two ways to get dollars when they really need them. They can participate in international trade, or they can sell their U.S. dollar-denominated assets. In healthy markets, they choose the first option (and are generally net buyers of U.S. assets with the dollars they receive through trade), but during a global slowdown or recession, that trade dries up.

So, when dollar debts need servicing, they are forced to sell U.S. assets to get dollars. In fact, that’s one of the key reasons why international central banks hold foreign-exchange reserves in the first place; to backstop external obligations if necessary.

This is why the dollar tends to briefly spike higher during recessions. International trade slows, dollar-denominated debts become an international problem, and everyone scrambles to get their hands on dollars.

And this is why the U.S. Federal Reserve has a $40 trillion problem at the moment. There is a global dollar shortage, and with international trade and commodity prices so low, dollars outside of the United States are in short supply relative to the size of the dollar-denominated debts that those dollars need to service.

Therefore, many institutions, both public and private, need to tap into their store of reserves, sell U.S. assets, and get U.S. dollars. Foreigners held $40 trillion in U.S. assets going into this crisis, of which nearly $7 trillion were U.S. Treasury securities (bills, notes, and bonds).

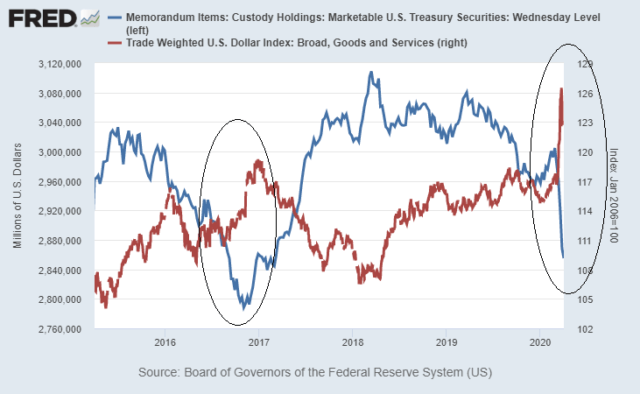

Foreign-holding data for U.S. Treasuries gets updated monthly and with a considerable time lag, but the large subset of foreign holdings of U.S. Treasuries at the Fed’s custodian account is updated more frequently. It’s an incomplete data set, but a more rapidly-updated one, and it shows us that foreigners sold at least $119 billion in Treasuries in the past four weeks:

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

That chart shows the trade-weighted dollar index in red and the value of Treasuries held by foreigners at the Fed as custodian in blue. Whenever the dollar spikes higher, foreigners start selling Treasuries.

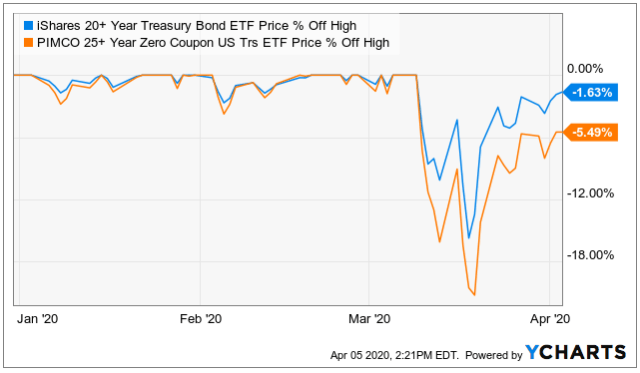

Those few weeks in mid-March, when the blue line went vertically down meaning that foreigners were rapidly selling Treasuries, is when Treasury yields spiked, Treasury bid/ask spreads widened to the point of becoming uninvestable, and when long-term Treasury security prices crashed. For example, the iShares 20+ Year Treasury ETF (TLT) suddenly dropped by 16% and the Pimco 25+ Year Treasury ETF (ZROZ) dropped by well over 20%:

During the long-duration Treasury security crash, the Fed then began rapidly ramping up its bond-buying program, and introduced a new range of dollar liquidity assistance operations.

The problem for the Fed is that there are not sufficient buyers for Treasuries anymore, especially at a time when foreigners were aggressively selling and some domestic leveraged hedge funds with Treasuries were unwinding positions.

Ever since the repo spike in September 2019, the Fed has been the main buyer of Treasuries via “money printing.” For lack of sufficient buyers, and a large amount of Treasury security supply due to large government deficits, the central bank is now monetizing U.S. government debt. In other words, the Fed is bailing out the Treasury market.

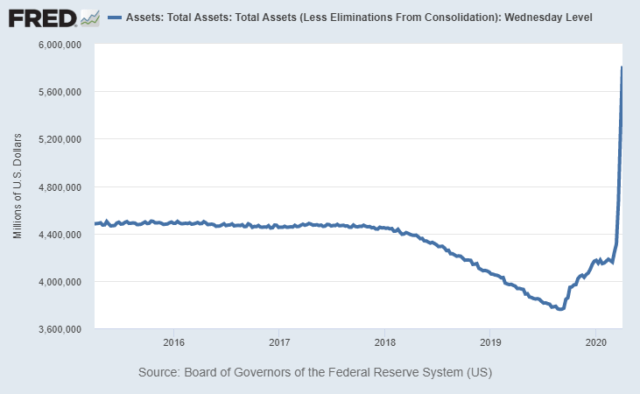

They do this by creating new dollars, and using those new dollars to buy Treasury securities on the secondary market. It was when Treasury security prices were crashing back in mid-March that the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet expansion went truly vertical:

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

The Fed’s balance sheet has shot up rapidly over the past month to buy Treasuries and other credit securities, to try to backstop the market and provide liquidity. They’re currently running at a $500 billion or more weekly expansion rate, although they are looking to slow that rate a bit in the weeks ahead.

To address this without having to outright buy everything, in addition to a record number of currency swap lines with other central banks now in place, the Fed has initiated a foreign repo operation.

Foreigners can now lend Treasuries to the Fed for dollars rather than outright sell Treasuries on the open market to get dollars, and this will apply to basically any country that has Treasuries and an account at the Fed.

This facility should help support the smooth functioning of the U.S. Treasury market by providing an alternative temporary source of U.S. dollars other than sales of securities in the open market. It should also serve, along with the U.S. dollar liquidity swap lines the Federal Reserve has established with other central banks, to help ease strains in global U.S. dollar funding markets.

In addition, the Fed recently changed leverage ratios for U.S. banks so that they can hold more Treasuries and less cash, which is another way of bailing out the U.S. Treasury market by trying to increase the available buyers, so that the Fed isn’t stuck as basically the only large buyer.

To ease strains in the Treasury market resulting from the coronavirus and increase banking organizations' ability to provide credit to households and businesses, the Federal Reserve Board on Wednesday announced a temporary change to its supplementary leverage ratio rule. The change would exclude U.S. Treasury securities and deposits at Federal Reserve Banks from the calculation of the rule for holding companies, and will be in effect until March 31, 2021. Liquidity conditions in Treasury markets have deteriorated rapidly, and financial institutions are receiving significant inflows of customer deposits along with increased reserve levels.

The foreign operations are particularly interesting to me. It’s an awkward position for the Fed, because they are lending dollars to creditors of the United States in exchange for collateral, so that the creditors of the United States don’t keep hard-selling U.S. assets, especially including U.S. Treasury securities. And any securities that those foreign creditors do sell, the Fed ends up buying outright.

Practical Applications

In the long run, this amount of deficit spending driven by new money creation is likely dollar bearish (and I think the consensus underestimates the extent of deficit spending in 2021, 2022, etc), but not until the global dollar shortage is sufficiently alleviated.

Right now, most central banks are treading water in terms of dollar liquidity until trade increases again. In response to foreign selling-pressure, the Fed will keep aggressively buying U.S. Treasuries and other securities, and keep providing liquidity with swaps and repo operations. We’ll see if they take other actions as well.

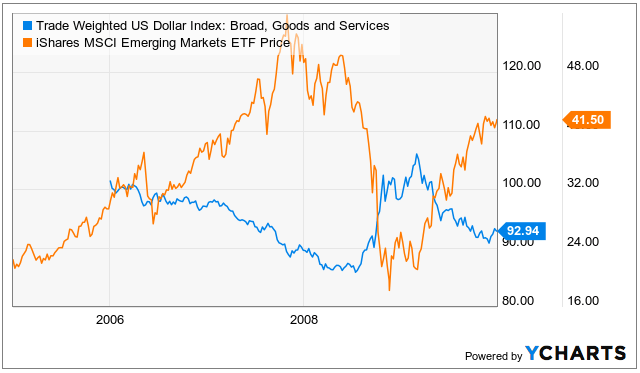

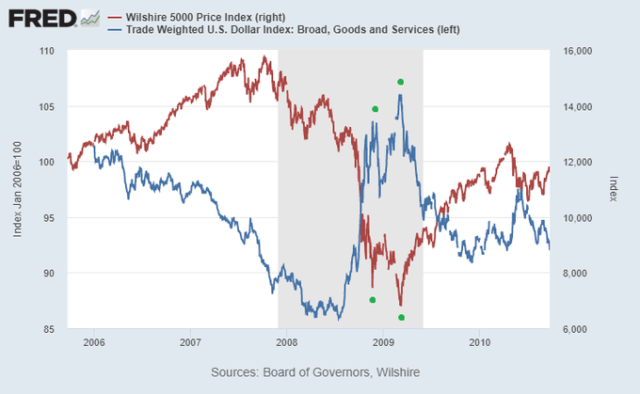

More broadly, if we look back at the 2008/2009 global recession, the U.S. stock market double-bottomed at the same time as the dollar index double-topped:

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

As long as the dollar remains this strong or strengthens further, it will be challenging for U.S. asset prices to rise on a sustained basis, in part because foreign holders of those assets would be more inclined towards being net sellers of those dollar-denominated assets to get dollars. The Fed’s liquidity operations and eventually a resumption of trade, can alleviate this dollar shortage in time.

But for as long as trade remains in peril due to COVID-19 shutdowns, this remains a risk. Only when the dollar falls vs. other currencies would it be easy for U.S. asset prices to rise on a sustained basis.

Emerging markets tend to be particularly dollar-sensitive, because they rely the most on foreign funding relative to their GDP. However, many investors treat emerging markets as one big basket, when the reality is that they are all quite different.

As it relates to the global dollar shortage, some nations have enough dollar-denominated assets to cover their dollar-denominated debts, while others do not.

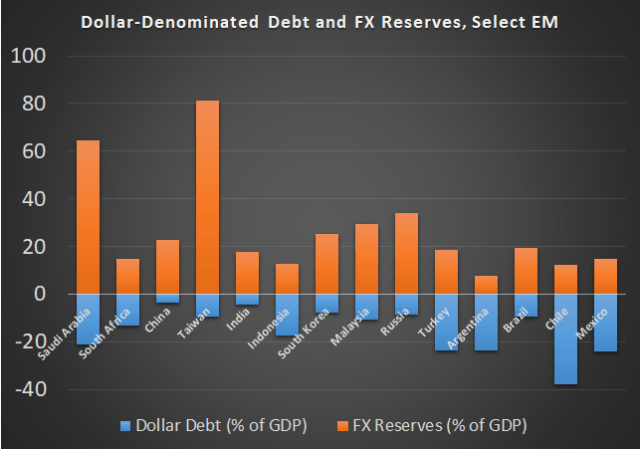

This chart shows the foreign-exchange reserves of several major emerging market nations as a percentage of their GDP, as well as their dollar-denominated debts as a percentage of their GDP, that they went into this crisis with:

Data Source: BIS and several central bank websites

The EM currencies with more FX reserves than dollar-denominated debts, such as Taiwan, South Korea, China, Malaysia, and Thailand, have held up rather well in this crisis. They have positive NIIPs and when push comes to shove, they have enough U.S. assets to sell to support their dollar-denominated debts. Although they are all under pressure at the moment like everyone else, most of them are creditor nations, which makes a large difference in the end.

On the other hand, the EM currencies with less FX reserves than dollar-denominated debts, and generally with negative NIIP positions, such as Turkey, Indonesia, Mexico, Chile, and South Africa, have lost more value over the past couple months. They are at the mercy of global markets and possible IMF assistance, because they don’t have enough dollar-denominated assets to cover their dollar-denominated debts.

They are debtor nations, like the United States, but with liabilities in a currency that they cannot print. These markets could have strong upside potential in a weakening dollar environment, but don’t really have any agency in the matter and thus have high risk.

There were some exceptions to this trend. For example, Russia has more FX reserves than dollar-denominated debts, and has a positive NIIP as a creditor nation, but as a major oil-producing nation, its currency has taken a hit anyway in this extremely low oil price environment. Saudi Arabia’s currency is pegged to the dollar so they didn’t experience a currency decline at the moment. Brazil’s currency was also hit a bit harder than its ratio of FX reserves to dollar-denominated debts were imply, because it’s also a large oil-producing nation.

So, in this EM currency sell-off, EM currencies that either had a large oil-producing reliance, or shallow FX reserves relative to dollar-denominated debts, were hit the hardest.

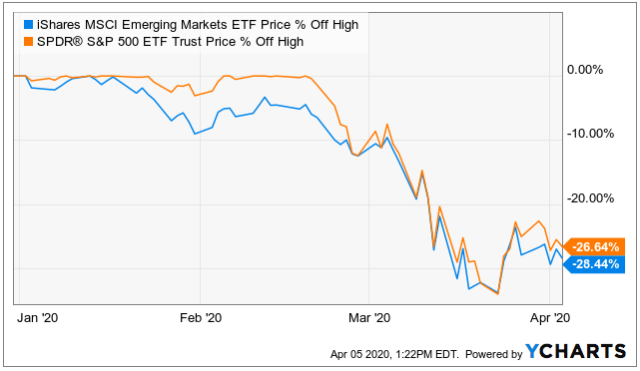

In this current sell-off overall, emerging markets have had very similar performance to the S&P 500 so far in terms of drawdowns from their YTD highs:

Back in 2008/2009, when the dollar rose in response to the global recession and dollar shortage, the MSCI Emerging Market Index that tracks equities in emerging markets (EEM) was crushed. The index was hit particularly hard because it went into that crisis extremely overvalued, unlike today where emerging markets were already priced for value.

When the dollar fell in 2009, after all of the Fed liquidity injections and the beginnings of a global economic recovery collectively alleviated the dollar shortage, the emerging market index shot up by 100% in about 10 months. For EEM, this translated into a move from roughly $20 to $40 per share.

As the dollar weakened, the monetary conditions in several EM countries effectively eased, allowing for a rebound in both fundamentals and asset prices.

It’ll be interesting to see how the next year or two plays out. Value-minded investors may wish to look into international markets that are currently at low valuations, but that are creditor nations with sufficient reserves to cover any dollar-denominated debts that they have. The risk/reward potential is rather favorable towards them in my view, for investors that take a long-term perspective.

Final Thoughts

Keeping an eye on the global dollar shortage, the Fed’s actions to supply dollar liquidity, and the resumption of global trade (in part dependent on higher commodity prices), is helpful for determining when U.S. and global asset prices will be under less selling pressure, all else being equal. That seems obvious, but many analysts are focused just on the economics and virus news, when in reality, the global dollar situation is similarly important.

Likewise, noting the difference between creditor nations and debtor nations in terms of NIIPs helps investors manage risk by seeing which currencies are most at risk in a dollar-spike scenario, and explains why the Fed is effectively forced to provide so many foreign liquidity operations if they want to support the U.S. treasury market.

We're looking for the best of both worlds, high-probability investing where fundamentals and technicals align, and we identified a ton of bearish setups in the past couple months leading up to this crash in our "Where Fundamentals Meet Technicals" series.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario