By: Hilal Khashan

The ancient Greek historian Herodotus described Egypt as the gift of the Nile River, because without the Nile, Egypt wouldn’t exist. But this lifeline, which supplies nearly 99 percent of Egypt’s water needs, is facing a threat the government believes could be disastrous for the country’s population.

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which is scheduled for completion in 2023, will be the largest hydroelectric dam in Africa and capable of generating more than 15,000 gigawatts per hour of electricity.

But for years, the project has been a major source of friction between Ethiopia and Egypt; Ethiopia even refused to attend talks in late February in Washington to resolve the dispute. Nine years into the dam’s construction, it seems Egypt’s options for blocking the project are shrinking.

The Making of the Standoff

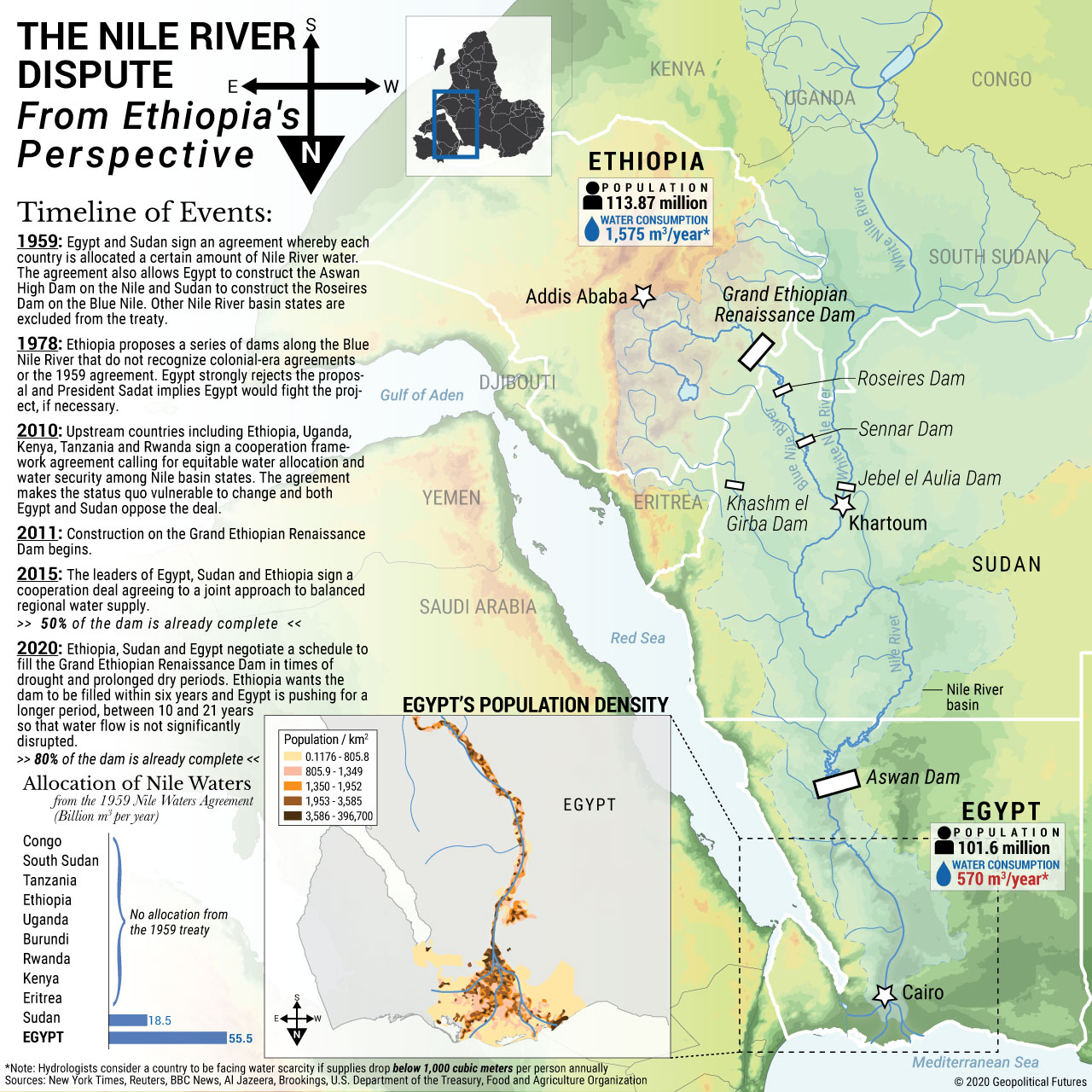

In 1929, the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty regulating use of the Nile River waters granted Egypt a yearly water allocation of 48 billion cubic meters and Sudan 4 bcm out of an estimated annual yield of 84 bcm.

The treaty entitled Egypt to veto any attempt by an upstream riparian state (especially Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania) to construct dams along the river. In 1959, Egypt and Sudan signed an updated agreement that increased their water allocation to 55.5 bcm and 18.5 bcm, respectively.

Since it did not participate in the negotiations, Ethiopia has refused to recognize the two agreements, dismissing them as vestiges of colonialism. It argues that Egypt has no right to claim the lion’s share of the Nile’s water and disrupt Ethiopia’s own development plans, including construction of the GERD, which lies on the Blue Nile, a river that originates at Ethiopia’s Lake Tana.

Ethiopia wants to fill the GERD reservoir, which has a total capacity of 74 bcm, within three years, but Egypt has proposed a seven-year filling period. Egypt also tried (unsuccessfully) to convince Ethiopia to reduce the reservoir’s capacity from 74 bcm to 14.5 bcm and the dam’s height from 145 meters to 90 meters.

Another subject of the dispute is water allocation. Egypt wants to be guaranteed 40 bcm of water annually, but Ethiopia is offering only 31 bcm. The U.S. has proposed that Egypt be granted 37 bcm, and it’s likely that, in a compromise deal, Egypt would be allocated 35 bcm. (Egypt, after all, never endorsed the 2010 Cooperative Framework Agreement, which was signed by Ethiopia, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Kenya and Burundi and which promotes equitable allocation of Nile River waters, because it would require Egypt to reduce its share of the water supply.)

Another factor complicating talks is Egypt’s unwillingness to compromise on its demand that the water level at the Aswan High Dam stay 165 meters above sea level.

It’s easy to see, however, why Egypt is so protective over the Nile. Egypt is an arid desert, and 95 percent of its population lives along the banks of the Nile and its delta. For Egyptians, access to the river is a matter of life and death, and the thought of going to war to secure the flow of its water runs deep in their collective consciousness.

Upon completion, the GERD will cut Egypt’s agricultural production by 50 percent, devastating water-intensive crops such as rice, potatoes and cotton. The GERD will also reduce Egypt’s hydraulic electrical supply by one-third, valued at $300 million, thereby increasing overhead costs for industry.

More than 5 million farmers will lose their jobs. They will likely relocate to densely populated urban centers, overburdening these cities’ failing infrastructure, exacerbating the country’s social insecurity, and creating a fertile breeding ground for Islamic militant groups.

Public Perspectives in Egypt and Ethiopia

Egypt’s minister of irrigation recently criticized Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed for reneging on his public oath not to compromise Egypt’s water security, but there’s little sympathy in Ethiopia for Egypt’s cause.

Ethiopians generally view Egypt as a colonial power and blame it for the high rate of poverty in Ethiopia. They accuse Egypt, whether correctly or not, of racism against Africa’s black populations and of taking part in the slave trade, particularly during the 19th century.

In his bid to seize the Blue Nile, Egypt’s Khedive Ismail sent his European and confederate-led army to Ethiopia. Egyptian troops took Massawa, a port city in present-day Eritrea, which precipitated the Ethiopian-Egyptian War of 1874-76. Egypt suffered a crushing defeat in the battles of Gura and Gundet, losing thousands of troops and an entire arsenal of rifles and cannons. The conflict was one of the factors that led to Egypt’s bankruptcy under Ismail.

One of the war’s lasting consequences is the lingering perception in Ethiopia of Egyptians as invaders. Their frequent threats to go to war over the Nile has sparked anger among many Ethiopians.

Former Egyptian President Mohammad Morsi publicly threatened to declare war on Ethiopia, and his predecessor, Hosni Mubarak, said he would have used Tu-160 bombers to stop Ethiopia from building the GERD if construction had begun during his time in office – even though Egypt did not even possess the Tu-160 at the time. Some have even claimed that President Anwar Sadat ordered airstrikes in the 1970s against Ethiopia to block it from building a dam on the river.

Egypt’s Options

But what can Egypt really do to stop the GERD’s construction? Egyptians have learned the lessons of their failed invasion of Ethiopia in 1974; they, and the Egyptian military, are not eager to go to war against Ethiopia again.

Egyptian rulers and military commanders have also learned from Egypt’s involvement in the unwinnable war in Yemen from 1962 to 67 and Gamal Abdel Nasser’s bluff in 1967 that led to a disastrous war with Israel. Egyptian officials understand, therefore, that a failed military campaign against the GERD would have devastating consequences.

Moreover, President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi wants to keep his grip on power and has no interest in initiating a foreign military intervention. In addition, the armed forces, which were focused on business and dominated more than half of the country’s economy during Mubarak’s administration, are ill-prepared for an armed conflict. Many army units are preoccupied with operating factories or involved in construction projects, and Egyptian military officers want to avoid any actions that might jeopardize their elevated socioeconomic status.

So, when el-Sissi met with the Egyptian command’s top brass, instructed them to prepare for the possibility of action and dispatched military and intelligence envoys to Khartoum, Juba and Addis Ababa, after Ethiopia boycotted the talks in Washington, it was clear that a full-blown war was extremely unlikely. Subtle threats to launch an airstrike against the GERD do not intimidate Addis Ababa because it knows such an attack is exceedingly unlikely for at least three reasons.

First, the dam site is well-defended. Second, U.S. mediation is still ongoing despite the failure of the talks in Washington. Third, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, which have close ties with Egypt, have significant economic interests in Ethiopia and would not approve of a strike against the country.

What’s more, Egyptian Rafale and F-16 Block 52 fighters lack the range to reach the GERD since the Egyptian air force does not have air refueling capability. Even if they reach the dam, it’s unclear if Egyptian pilots have the skill needed to negotiate the elaborate missile defense systems that protect the construction site, let alone destroy its thick concrete walls.

Egypt has a large and well-armed standing army and a modern navy that includes two Mistral Helicopter warships and fours Gowind-class corvettes, but they are ill-suited to attack the GERD.

For Egypt, diplomacy is the only option available, even though its bargaining power is limited.

The GERD’s construction is approaching completion, and Abiy has the support of the upstream riparian states, as well as Sudan, which opposed the Arab League’s draft resolution supporting Egypt in its current dispute with Ethiopia. Egypt cannot count on the support of the U.S., which has cautiously stressed the need for mutual respect among the Nile Valley states.

The only real course of action for Egypt is to conserve water as much as possible, invest in water desalination plants, and normalize its relations with all countries in the Middle East because it needs all the foreign assistance it can get.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario