Owing to the missed opportunities of the post-2008 period, most Latin American and Caribbean governments have very limited fiscal space with which to manage the COVID-19 pandemic. Nonetheless, if their limited ammunition is well-aimed, it could go a long way toward mitigating the crisis.

Alejandro Izquierdo , Martin Ardanaz

WASHINGTON, DC – Confronting a pandemic is a grueling trial even for the most advanced economies. For indebted governments in Latin America and the Caribbean, it is harder still. Many countries’ fiscal positions are worse now than they were when the 2008 global financial crisis erupted.

Worse, stimulus policies that work in normal times will not work against the fallout from COVID-19, and financing is becoming increasingly scarce as investors flee to safer assets and markets.

Between 2008 and 2019, Latin America and the Caribbean’s average overall fiscal balance slid from -0.4% of GDP to -3%, and average public debt grew from 40% of GDP to 62%. These numbers are a consequence of missed opportunities, particularly during and after the “Great Recession” in the United States.

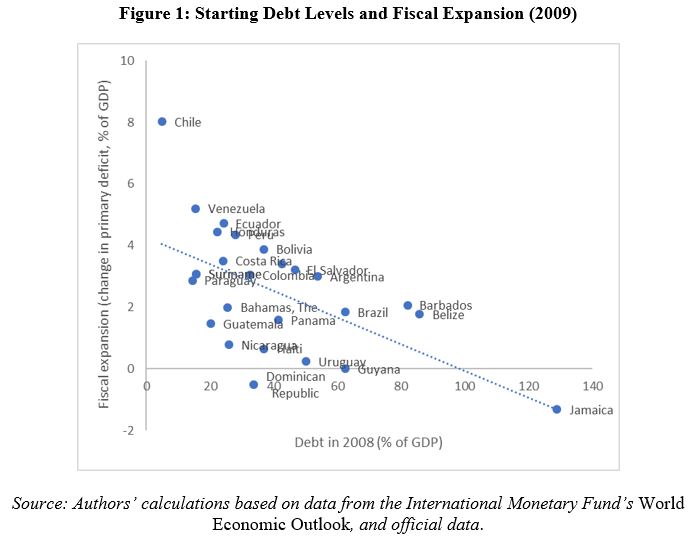

In 2008-09, most governments in the region increased expenditures to sustain aggregate demand. Fiscal packages averaged 3% of GDP, but differed across countries. Those with low debt levels were able to implement substantial stimulus measures, whereas those with high debt had to undergo an economic contraction.

Given today’s higher debt levels, the region will be able to respond with a fiscal expansion of only around half the size of that in 2009, on average. Whereas Chile and Peru have room for spending, Argentina, Ecuador, and other countries will struggle.

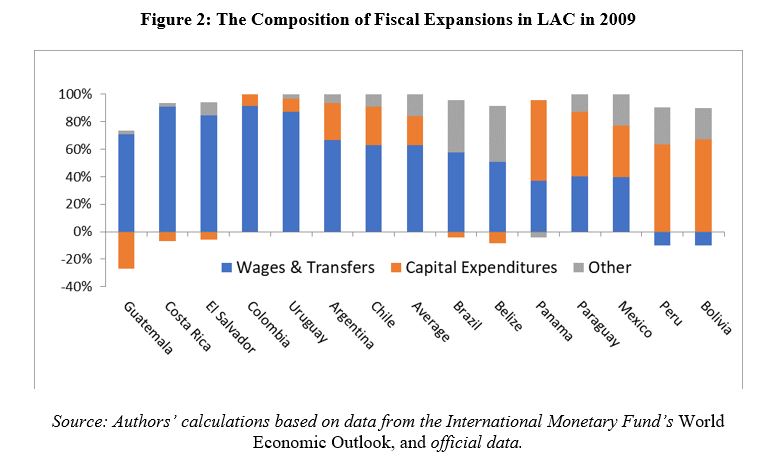

Another issue will be the composition of fiscal stimulus, which can have far-reaching implications for the future. True counter-cyclical policies call for only transitory expenditures. But in the 2009 fiscal expansion, almost two-thirds of spending went toward higher salaries and permanent transfers, which are difficult to reverse, and thus not sustainable. By ratcheting up these current expenditures, many countries baked in future fiscal deficits.

Yet another issue is access to financial markets. The region is already paying 700 basis points over US Treasuries, on average, to service its debt. And while investors are still open to buying assets from the region, a flight to higher-quality assets is already underway.

According to the Institute of International Finance, cumulative outflows from emerging markets since January have surpassed the levels observed during the global financial crisis. For countries like Argentina and Ecuador – with credit spreads above 4,200 basis points – the only option is to secure loans from multilateral institutions.

Owing to these circumstances, the overall size of the region’s fiscal packages will have to be smaller than in the past, unless countries are willing to assume additional macroeconomic risks, or to cut other outlays to make room for programs to fight COVID-19. Obviously, limiting the spread of the virus, boosting health expenditures, and avoiding a health-infrastructure collapse are immediate priorities.

The time for achieving sustainable, broad-based growth will come later. Besides, standard macroeconomic stimulus policies may not even be effective now. While capital expenditure is typically the best instrument for counter-cyclical policies (because it has the largest fiscal multiplier), it will not necessarily work at a time when construction sites and many other workplaces have become hubs of contagion.

Policymakers designing pandemic-response packages also will need to ensure that expenditures are temporary, so that they can be dialed back when the crisis passes. Many people will lose income as a result of self-isolation, so subsidy programs for the poor and those who rely on the informal economy are imperative. To avoid permanent increases to existing transfer programs, these subsidies should be channeled through separate accounts with clear sunset clauses.

Moreover, governments can increase the efficiency of spending. A recent report from the Inter-American Development Bank finds that much of the social spending intended for the poor has actually been going to the non-poor, and that there are significant inefficiencies in public-sector wages, and goods and infrastructure procurement.

All told, this waste amounts to 4.4% of GDP, which is substantial enough to cover much of what is needed for the current emergency. To be sure, these resources would not become available quickly. But one option is to front-load crucial additional expenditure in, say, health care, while immediately adopting policies to cut waste, thus ensuring fiscal sustainability in the future.

Tracy Wen Liushares harrowing first-person testimonials from the front lines of the COVID-19 outbreak in China.

Governments with the fiscal space to do so could go further. For example, they could offer temporary tax deferments for households, firms, or even entire regions struck hard by the coronavirus. The point is to provide as much liquidity as possible while avoiding tax holidays, in order to preserve future sustainability.

Finally, governments will need to step in to sustain credit markets. Many firms will find it difficult to refinance even short-term loans, which will raise the risk of massive layoffs. To prevent liquidity problems from becoming solvency problems, governments can intervene with asset-purchase programs.

The challenge for Latin America is to do this at the necessary scale, transparently, and with clearly targeted programs. Otherwise, loans could turn into grants that the region cannot afford.

Meanwhile, larger, systemically important countries in the region may be able to secure access to swap lines from the US Federal Reserve. Smaller countries will have a better chance of getting loans from multilateral institutions, but that will be challenging for larger, non-systemically important countries, given the limited resources available. As such, multilaterals should have their capital increased.

Despite the current constraints, fiscal policies can still play an important role in saving lives and mitigating the economic costs of the coronavirus in Latin America and the Caribbean. Ammunition is scarce. But if it is well-aimed, it could go a long way.

Alejandro Izquierdo is Principal Research Technical Leader at the Inter-American Development Bank.

Martin Ardanaz is Fiscal and Municipal Management Specialist at the Inter-American Development Bank.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario