European bank stocks are back at levels last seen in the 1980s as investors struggle to size up the impact of the economic shutdown

By Rochelle Toplensky

Like other European banks, ING appears heavily exposed to the troubled oil-and-gas industry.

Photo: Geert Vanden Wijngaert/Bloomberg News .

A problem for airlines is a problem for banks. A problem for oil producers is a problem for banks. A problem for restaurants is a problem for banks.

Sitting at the heart of the economy, banks are spared no pain. They are usually protected by the diversity of their lending—only one or two industries or regions struggle at a given time—but the widespread economic shutdown to contain the novel coronavirus is a crisis for nearly everyone, everywhere.

Bank investors are understandably nervous. In Europe, share prices have nearly halved this year and are back at levels last seen in the 1980s, while the cost of insuring against bank defaults using credit default swaps has been rising since late February.

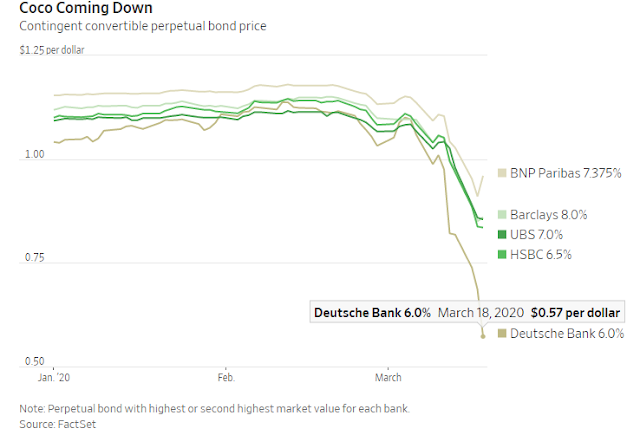

So-called additional Tier 1 capital bonds—perpetual bonds that can be converted into equity or written off if the bank’s capital ratio falls below a certain level—have plunged around 20% or more this month.

Holders of these AT1 bonds, also called contingent convertibles or cocos, could lose out if a lender needs more capital. They pay high interest rates to compensate for that risk. Months ago that seemed quite a safe bet to yield-hungry investors, but not anymore.

Lenders are much stronger now than a decade ago. Since the 2008 financial meltdown they have built up substantial capital under acute regulatory scrutiny. Yet many are still wondering if the buffers will be big enough.

The root problem is that the scale of the coming default wave is impossible to assess. Even under normal circumstances only a bank truly knows its loan book.

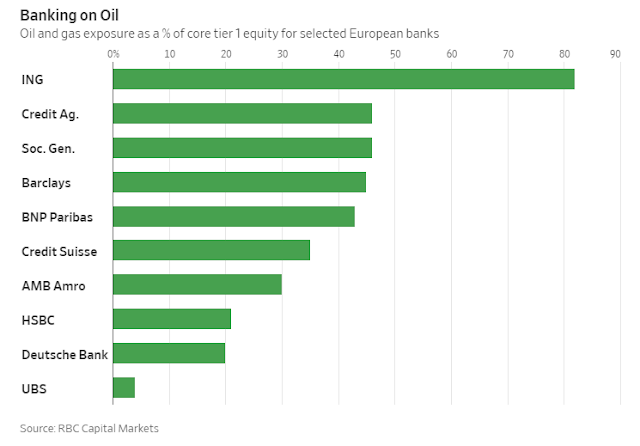

Financial reports include more information than before, so we can glean a few things. In Europe, Dutch lender ING appears heavily exposed to the troubled oil-and-gas industry. So do Barclays and three French banks— BNP Paribas, Crédit Agricole and Société Générale —according to analysts at RBC Capital Markets.

That only tells part of the story, though. Are those loans for risky new oil exploration projects or building a chemical plant? Is the borrower a behemoth with relatively low debt levels or a smaller company sailing close to the wind?

Oil producers are a major concern because they borrow billions and are dealing with brutally low prices. But what about a bank’s loans to airlines, leisure companies and even retailers? As Europeans and Americans settle in at home to work and play, many industries face a serious cash crunch even in the best-case scenario of a short lockdown.

Interest rate cuts may help a few borrowers and delay defaults in the immediate crisis, but longer term they make life harder for lenders struggling to generate profits. Governments’ apparent willingness to backstop loans and unleash fiscal policy is more welcome.

China’s apparent shift into recovery gear offers some grounds for optimism about the length of the U.S. and European lockdowns and their economic impact. But the Chinese rebound remains uncertain, and Western economies, governments and lenders are fundamentally different. There are no useful Western precedents to a pandemic-induced recession.

Investors probably won’t get a proper read on the situation until banks report first-quarter numbers in April. Newish accounting rules require European and U.S. banks to book loan losses earlier than before. Although this accelerated recognition could stoke fears and amplify the cycle, it should also provide valuable detail on which banks are most exposed to the unfolding crisis.

One thing is certain: The next bank earnings season will be the most closely watched in years.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario