By: Hilal Khashan

The coronavirus has stunned a disbelieving world. By the time we understood the gravity of the situation, it had already become a pandemic. The Arab world is as guilty as any other region in underestimating the threat.

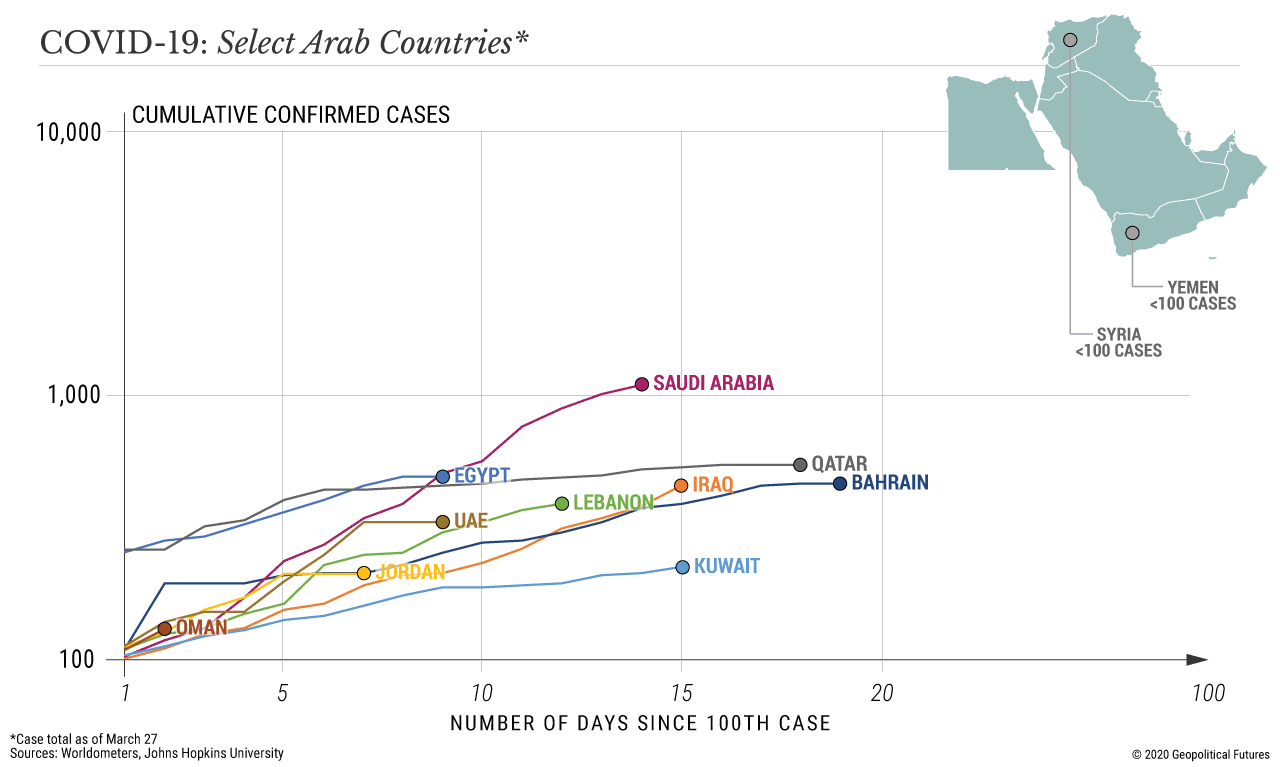

Except for wealthy Gulf Cooperation Council states that responded reasonably quickly, most Arab governments seemed to hope that the crisis would resolve itself on its own. Clearly, it hasn’t.

But differences in the reactions among Arab governments, religious officials and the public bring into relief some of the issues that undergird Arab society.

In addition to curtailing air and ground traffic, belated state measures to contain the virus included curfews, social distancing, the suspension of economic and bureaucratic operations and the closure of schools, universities and places of worship.

Saudi Arabia closed Islam’s holiest sites in Mecca and Medina, and the Assembly of Catholic Ordinaries of the Holy Land shut down the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. Arab officials were hesitant to adopt such stringent measures, of course, because they knew how poorly the public would receive it.

Examples of mishandling abound. In February, when the Lebanese media pressed the minister of health about why he had not suspended flights from Tehran to Beirut, he admitted that the decision was political, clearly because of Hezbollah’s veto.

Unaware of the nature of the virus, he assured the public that Lebanon had the vaccine for it.

When the virus spread in China, the Egyptian minister of health visited Beijing in a show of solidarity instead of taking measures to prevent its spread to Egypt.

In Syria, the government opted for denial as the best option to combat it. The police in Damascus arrested a physician because he reported the first positive COVID-19 case in his hospital.

He had to rescind the announcement as a misdiagnosis. The Ministry of Health told hospitals to report deaths from the virus as cases of acute pneumonia or advanced pulmonary tuberculosis.

Iraqi Shiite leader Muqtada al-Sadr, some of whose followers believe his dress has curative powers, said he opposed the use of U.S drugs to fight the virus and accused President Donald Trump of spreading the disease among his enemies.

The religious establishment in all Arab countries failed to urge the ruling elite to take immediate action to contain the spread of the virus. Religious leaders didn’t demand the closures of holy sites, but they defended the governments’ decisions immediately after the fact. Some mosques, particularly in Iraq and Lebanon, ignored government calls to close their doors.

Others kept their outer gates open to allow worshippers to participate in congregational prayers and made sure to cover the floor with rugs for their convenience. Some clerics proposed that worshippers maintain one meter of distance between each other and isolated those suspected of carrying the virus in a separate prayer room.

Muslim clerics neglected to present the virus in life-or-death terms, as they often do during times of crisis, partly because of al-Jabr, one of the seven articles of Islamic belief that emphasizes divine predestination.

The concept submits that man does not possess free will and that God determines the fate of human life. There is, moreover, a complete absence of jurisprudence of foresight and expectation. Religious scholars, especially Sunni scholars, continue to search for edicts dating back to the formative years of Islam. Unfortunately, they live in the present with the mentality of the past. Many people, including clerics, have no clue about the virus and how it is transmitted.

They even claim that what you don’t see doesn’t exist. Some clerics want the virus to afflict a loved one to validate its existence. When they do concede to reality, they claim that God afflicts whoever he wills to test their faith. Religious scholars who oppose closing mosques argue that preserving the faith has priority over safeguarding an individual’s health or life.

Hanbalism, the most austere school of Sunni jurisprudence that gave rise to Salafism, advocates the literal interpretation of religion and ascribes human qualities to God. Abdul-Aziz bin Baz, the late Grand Mufti of Saudi Arabia, even ruled that the earth is flat and the sun revolves around it. Most clerics in the Arab world are either government employees or the product of the oil boom in the 1970s and massive Saudi spending to spread Wahhabism and Salafism to appease its powerful religious establishment.

Practicing Muslims believe that congregational prayers are more spiritually rewarding than praying alone; the more participants, the better. Prayers attract worshippers because of the widespread belief that God’s watchful providence covers their participants. Traditional Muslims believe that God is their protector, and nothing could happen to them that he did not ordain.

Had Arab governments left people to their own devices, mosques would still attract large crowds of worshippers. In popular Islam, mosques are both spiritual edifices and healing places. Plagues and diseases caused by sins can be cured by praying in mosques. They accept that one can catch the virus in a mosque. In this case, it is because God has willed it so and, therefore, there is no escape from it.

It is a time-honored practice for congregational worshippers to exchange handshakes and hugs after the end of the prayer. During prayer, they kneel on carpets, potentially carrying pathogenic bacteria and viruses. Christians tend to display similar behavior. In one Lebanese Maronite Christian church, the faithful refused hand communion and insisted on receiving communion on the tongue in defiance of the mandatory decree by the church to prevent the spread of the virus.

Traditional and poorly educated people, especially if their knowledge about Islam is superficial, fall victim to religious fatalism and lead a life of cultural apathy. Many people exhibit a reckless disregard for government coronavirus awareness campaigns and warnings against public gatherings.

On Beirut’s waterfront corniche that attracts strollers and joggers from all walks of life, the municipal police had to intervene and disperse crowds after the spread of the virus. Similar scenes took place in Baghdad, Algiers, Khartoum and Cairo. A large group took to the streets of Alexandria, Egypt’s second-largest city, to plead with God to remove the coronavirus.

Skeptics linked the virus to conspiracy theories and accused China of spreading it to destroy Muslims. Others viewed it as divine punishment for infidels. A Syrian preacher told his congregation during a Friday sermon that the virus is a soldier of God on a mission to annihilate China’s communist Buddhists because they persecute Uighur Muslims. (Muslims, he said, contract the virus for other reasons, mostly because God is testing the strength of their faith.)

The inability to understand how the virus spreads and how to cope with it breeds imaginary explanations. Faith that God can immunize us against the virus without any precautionary measures on our part pervades the minds of traditional Muslims.

The practice of kissing the shrines of Muslim holy figures, be they Sunni or Shiite, and appealing to them for a cure to the virus continues unabated because of clerical support.

There are, of course, rational religious people who abide by the rules of the temporal law, and atheists who say they do not trust conventional medicine and believe instead in unproven alternative medicine.

Christianity reformed itself in the 16th century, and so did Judaism in the 19th century. Islam still awaits its own reforms to face the challenges of modernity.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario