A Perfect Storm For Emerging Markets

Pretend for a minute that it’s 2019 and you’re Brazil. Or maybe Turkey, your choice.

You’ve got a lot of infrastructure to build if you want to keep your people happy, and to fund those projects you’ll need to borrow a lot of money.

That’s not a problem, because borrowing is easy. The whole world wants to give you US dollars at interest rates that are shockingly low compared to what prevails in your domestic financial markets.

And, icing on the cake, your experts tell you that the dollar is likely to fall versus your country’s currency, making it even easier to pay off those loans. So you load up, borrowing as much as the market will bear and use the proceeds to buy higher-yielding local bonds (thus earning a nice spread) while starting on those roads and bridges. It feels like a win-win with minimal risk.

Then the coronavirus happens. The US dollar strengthens on safe-haven demand and your local currency plunges on a global “risk-off” spasm.

And articles like the following start showing up in the global press:

Coronavirus jolts vulnerable economies

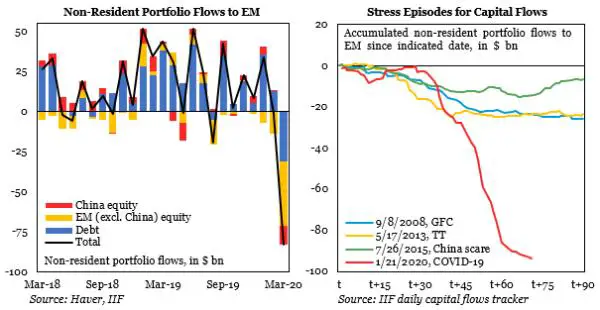

(NHK Japan) – The Institute of International Finance says that its latest data shows money is rapidly “disappearing” from emerging markets. Since late January, cumulative outflows have surpassed levels observed at the peak of the 2008 global financial crisis.

In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, investors are quickly selling emerging market currencies such as the Brazilian real, Indonesian rupiah, Russian ruble, and Turkish lira to buy up the US dollar.

Kristalina Georgieva, the head of the International Monetary Fund, noted in a recent statement that investors have removed 83 billion dollars’ worth of money from emerging markets, the largest capital outflow ever recorded.

For these countries, the problems don’t end there; they have been hit hard by plummeting oil and commodity prices. On March 18, crude prices fell to 20 dollars a barrel, half the price of just a few weeks ago. This is a crippling blow for the many emerging economies which are oil and commodity exporters.

Some of these countries were already in vulnerable positions. The debt service ratio measures a country’s debt interest payments in relation to its export earnings. The figure is said to measure the strength of a country’s financial position: the lower the ratio, the healthier the national finances. For most countries, the number falls somewhere between 0 and 20 percent.

According to Atsushi Nakajima, chairman of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade, and Industry, Argentina’s number stands at over 60 percent, while Turkey’s and Brazil’s exceed 30%. If more emerging countries see their ratios increase, it would lead to heightened concerns over the stability of the global financial system. Such a situation could quickly develop into a debt crisis.

———————

Dollar strength exposes cracks in Asian emerging-market debt

(Nikkei) – Some $1.4 trillion worth of U.S. dollar-denominated bonds are outstanding from Asian countries, with more than half of that from China, according to Dealogic.

The resilient U.S. dollar and the resulting weakness in emerging-market currencies amid the coronavirus pandemic is increasing the risk of default on Asian companies’ corporate debt, potentially triggering a wider credit crisis.

About $115 billion in Asian emerging-market debt is set to mature this year and $200 billion next year, according to data from Dealogic. The dollar’s 7% climb this month against a basket of currencies and a 243-basis-point blowout in Asia ex-Japan credit spreads could complicate the task of refinancing, and analysts are predicting that some stretched companies will have to seek restructurings with bondholders.

“At the peak of the last big market sell-off [in 2018], there were 150 bonds in the J.P. Morgan Asia Credit Index yielding over 10%. That number is now 301,” said Jim Veneau, head of fixed income for Asia at AXA Investment Managers.

Which brings us to the real question facing the developed world, which is: Who owns all this soon-to-default emerging market debt? And the answer is, as usual, lots of different people. Big Western banks are on the hook for many of the loans. Hedge funds and pension funds own many of the bonds.

And the emerging market bond funds that far too many retirees were talked into adding to their nest eggs own plenty.

So when EM debt defaults, pretty much everyone feels the pain. Though it’s not clear whether anyone will notice, given what else is going on.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario