By: Ridvan Bari Urcosta

Last week, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky met with his Turkish counterpart, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, in Kyiv. During the visit, Erdogan promised to strengthen military and economic cooperation with Ukraine and emphasized his support for the Crimean Tatars. After all, Crimea has long been central to Turkey’s relationship with Ukraine.

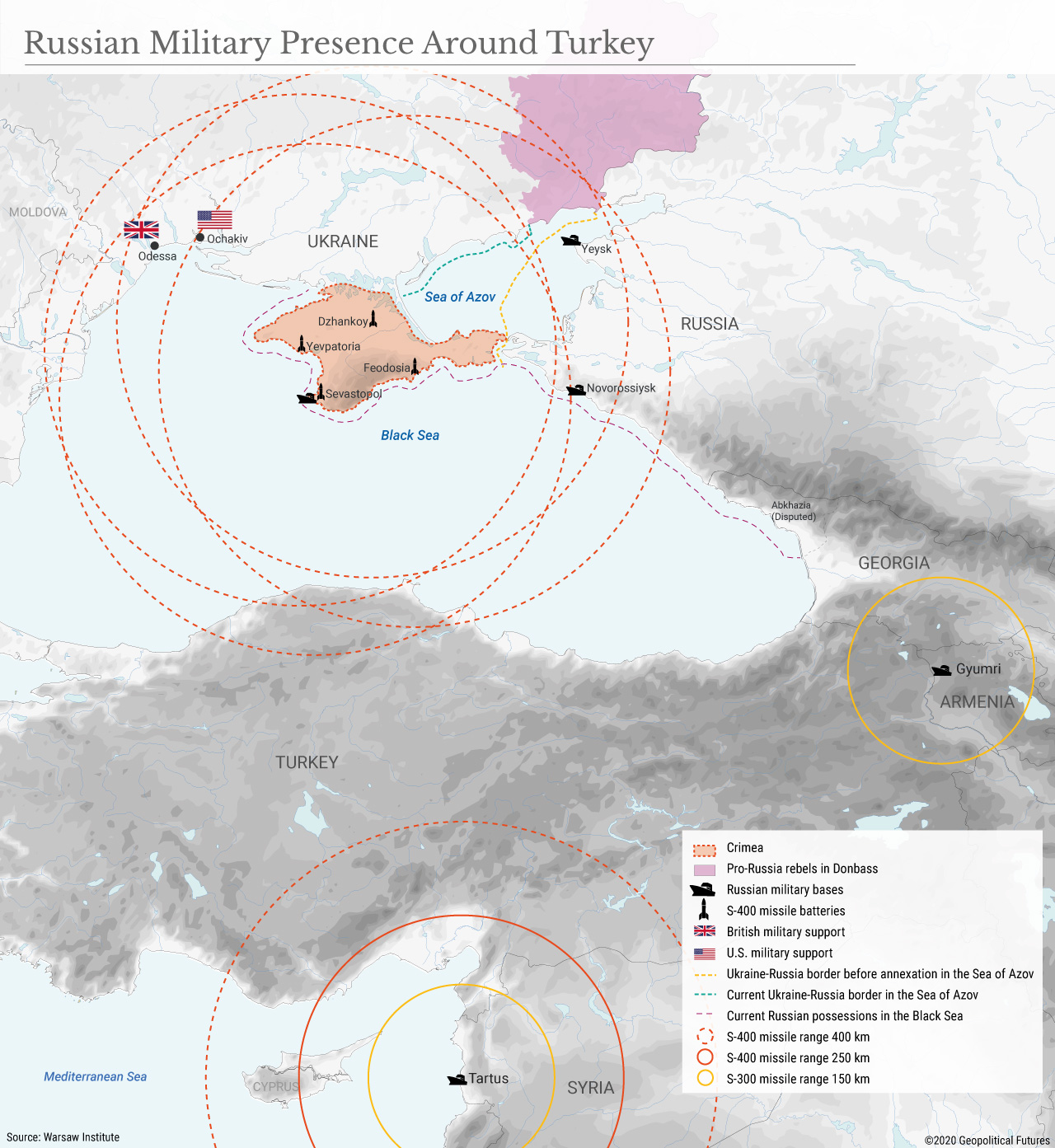

Another key factor in this relationship is a common adversary: Russia. Ankara has sought to use Ukraine and its long-standing connections there to its advantage as it engages with Moscow. Erdogan’s trip to Kyiv happened to coincide with a recent shift in Turkey-Russia relations, particularly in Syria, where the two countries appear to be getting closer to a potential confrontation in Idlib, and in Libya, where they support opposing sides in the civil war.

Erdogan knows that Ukraine is an especially sensitive issue for the Kremlin, which sees a partnership between its critical buffer to the west and its historical rival to the south as a threat to its strategic interests in the Black Sea. By building closer ties to Kyiv, Ankara sees an opportunity to block Russian expansion in a strategic region historically known as the Pontic Steppe.

Turkey’s Interests in the Pontic Steppe

At its peak, the Ottoman Empire stretched from the Atlas Mountains in the west to the Zagros Mountains and the Persian Gulf in the east, and to the Balkans and the Caucasus in the north.

Former Ottoman territories still play a large role in contemporary Turkish foreign policy, particularly in Erdogan’s ambitious agenda to re-establish Turkish influence in the Persian Gulf, Levant, Black Sea, Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa.

As GPF forecast, Turkey has already begun to expand its presence in some of these areas, but while its involvement in places like Syria and the Eastern Mediterranean has garnered much attention of late, its relationship with Ukraine seems to have been mostly overlooked.

Crimea is at the heart of Turkey’s engagement with Ukraine. Beginning in 1475, the Crimean Peninsula came under Ottoman rule, though it still had some autonomy. The Crimean Khanate was useful to the Ottomans as a bulwark against the Russians in the Black Sea for three centuries. With the Ottomans’ help, the khanate controlled strategically important chokepoints in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov.

These chokepoints are still an integral part of modern-day Turkey’s geopolitical strategy and are crucial in understanding Turkey’s quest to expand its influence north. The Ottomans also controlled three regions north of Crimea that now belong to Ukraine: Odessa, Nikolayev and Kherson. When the Ottoman Empire lost the Crimean Khanate in 1783, it was forced to retreat from many other theaters, particularly the Caucasus and the Pontic Steppe. The Russian Empire then took over these areas that had been occupied by the Turkic people for centuries.

Following the Russo-Crimean Wars in the 16th century, competition between the Ottomans and Russia in Crimea expanded. After the Russo-Turkish War of 1768-1774, Crimea was officially handed over to the Russians with the signing of the 1774 Treaty of Kucuk Kaynarca, regarded as a watershed moment marking the beginning of the Ottoman Empire’s protracted decline.

After years of revolt against Russian rule, the Russian Empire annexed Crimea in 1783 and began to Slavicize Crimea and the surrounding areas. (Interestingly, Russia’s revival of the Novorossiya, or New Russia, concept in 2014 included claims to the Pontic Steppe. Russia used this concept to justify its incursion into Donbass in eastern Ukraine, though Novorossiya extends beyond Donbass to include Kharkov to the north and Odessa to the west.)

Russia had realized that without destroying the Crimean Khanate, it would have been nearly impossible to carry out military operations deep into the Balkans because the Turks and Crimean Tatars would have been able to sever Russian communications and lines of supply in central Ukraine. With Crimea under Russian control, Russian expansionism was formidable and could be stopped only with the emergence of the Russian Revolution in 1917. The Russian Empire thus expanded in two directions: into the Caucasus and into the Balkans.

For Turkey, the loss of Crimea once again reinforced the geostrategic importance of the Pontic Steppe (present-day Ukraine). Though Russia has failed to regain control of much of this area, it has managed to bring Crimea under its jurisdiction, which Turkey will inevitably see as a threat to its security. Turkey’s strategy in Ukraine, therefore, has been to support not just the Crimean Tatar nation but also Ukrainian sovereignty and territorial integrity. So long as the Tatars – who, for the most part, opposed Russian annexation and pledged their support to Kyiv – remain a factor in Crimea, Ankara will have some degree of influence on the península.

Turkey-Ukraine Relations After 2014

Russian President Vladimir Putin once called the Soviet Union’s collapse “a major geopolitical disaster.” And it’s not hard to see why. Russia had lost access to Crimea’s strategic ports, controlled just a small portion of the Black Sea coast and required access to the Turkish-controlled Bosporus just to be able to conduct maritime trade beyond the Black Sea. Turkey, on the other hand, had superior naval forces, control over strategic waterways (namely, the Turkish Straits), and more sovereignty over a larger portion of the Black Sea coast than any other country in the region. Suffice it to say, Turkey was satisfied with this state of affairs.

That is, until 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea. Since then, Moscow’s position in the Black Sea has strengthened, and the possibility of confrontation between Turkey and Russia in the Black Sea has intensified. Indeed, without control of Crimea, Russia likely would not have been able to conduct military and naval operations in its Syrian campaign through the Eastern Mediterranean.

Turkey was alarmed over the rapid geopolitical developments in the region and expressed its support for Ukrainian territorial integrity from the very beginning of the Ukraine crisis, even sending then-Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu to Kyiv for talks in early 2014. To this day, it has not recognized Crimea as part of Russia and maintains close relations with the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People, a body that represents Crimean Tatars and was banned by Russia in 2016.

Turkey and Ukraine have also expanded military cooperation; they held joint naval exercises in the Black Sea in March 2016, just a few months after Turkey’s downing of a Russian military jet near the Syrian border. For Ankara, showing that it has a presence in Russia’s critical buffer is a way of increasing pressure on Moscow.

However, military cooperation between the two countries goes back further than 2014. In fact, Turkey has some of the closest ties to Ukraine’s defense industry of any NATO member.

Ukraine’s state-owned defense firm Ukroboronprom has collaborated with Turkish companies Hevelsan, ASELSAN and Roketsan, among others. Last year, the two countries set up a joint venture focused on precision weapons and aerospace technologies. They also participated in joint projects to create An-188 and An-178 military transport aircraft, active defense systems for armored vehicles and radar systems.

In 2019, Ukraine acquired Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 drones, armed with high-precision MAM-L bombs purchased from Roketsan. Ukrainian experts are expected to help Turkey develop a new, indigenously built battle tank. They even discussed collaborating on corvettes and surface-to-air missiles.

One could argue that Turkey is using Ukraine to sidestep collaborating with Russian defense companies and also to bolster its own defense industry to reduce its dependence on NATO. In the process, the Ukrainian defense sector, which was hurt by the complete disengagement with the Russians, is also benefiting from collaborating with a NATO member, bringing its industry into line with NATO standards.

Economic cooperation has also been growing. During last week’s meeting, Erdogan and Zelensky agreed to complete talks on a free trade agreement, negotiations for which began under former President Petro Poroshenko. Zelensky appears ready to sign a trade deal, even though the benefits to Ukraine, as the weaker of the two economies, are still uncertain.

With a deal in place, the two countries hope to bring trade turnover to $10 billion. Turkey also promised to give Ukraine $36 million in military support. Zelensky, in return, promised to help Erdogan on security issues, instructing Ukraine’s Security Service to look into Ukrainian educational centers linked to Turkish cleric Fethullah Gulen, who Erdogan has accused of orchestrating a coup attempt against him.

In an effort to attract more foreign capital, Zelensky has said he wants to lift a moratorium on farmland sales, raising the issue last year during a speech in Istanbul. (The Ukrainian parliament has since passed a bill that would allow the sale of land to foreigners, except Russian citizens and corporations, beginning in 2024.)

Ukraine has also welcomed the Trans-Anatolian pipeline project, which could bring natural gas from Azerbaijan via Turkey to Ukraine, as well as other parts of Europe. Alternative sources of energy are becoming increasingly important as Russia becomes more reluctant to deliver energy to Turkey and Europe via pipelines that pass through Ukraine, such as the Trans-Balkan pipeline.

In addition, Crimea has continued to play a key role in Ukraine-Turkey relations. As part of Turkey’s quest to promote the concept of Neo-Ottomanism, Turkish officials have emphasized the historical and ancestral links between Turkey and the Crimean Tatars. Former Foreign Minister Davutoglu even regularly met with leaders from the Crimean Tatar community.

Before 2014, this may have irritated Kyiv, but since the Russian annexation, Crimean Tatar representatives have been included in delegations on official visits. As Davutoglu once put it, Crimea is now considered “a bridge of friendship” between the two countries.

Turkey is also the top trade partner for the three regions of Ukraine north of Crimea: Odessa, Nikolayev and Kherson (all part of the Pontic Steppe). And Turkish ally Qatar recently won a bid to develop Olvia port in Nikolayev region, which will be the biggest foreign investment in a Ukrainian port in history.

Immediately after Crimea’s annexation, Turkey and the Crimean Tatars asked Kyiv for permission to build ethnic settlements in Kherson (once part of the Crimean Khanate) for Tatars who had fled Crimea. Poroshenko avoided making a decision on the issue, but Zelensky has pledged his support. Russia will likely stir up anti-Tatar sentiments among locals there to try to convince them to oppose it.

There are between 1 million and 3 million Crimean Tatars in Turkey, most of whom tend to be pro-Ukraine. Erdogan, therefore, has a political incentive to woo the region. In 2017, he spoke with Putin on behalf of two Crimean Tatar leaders who were jailed for opposing the annexation. And recently, Zelensky asked Erdogan to intervene in a case over Crimean Tatars convicted on extremism charges after Russian authorities accused them of being followers of Hizb ut-Tahrir, a group that has been banned in Russia.

In addition to political, economic and military links, the two countries have religious connections. In 2019, the Istanbul-based Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople approved the official decree splitting the Orthodox Church of Ukraine from Russia. Erdogan has declined to comment on religious issues in Ukraine but has met with Bartholomew I of Constantinople, who signed the decree.

It’s worth noting, however, that within the Ukrainian political elite, there is some concern over Turkey’s true intentions and loyalties, especially considering that Ankara has not joined the West in applying sanctions against Russia over Crimea. Ukraine has viewed with suspicion the budding relationship between Putin and Erdogan, which continues despite their countries' disagreements.

When Ukraine hoped to import liquefied natural gas through the Black Sea to reduce its reliance on Russian energy, Turkey refused passage of LNG tankers through the Turkish Straits. Turkey has meanwhile kept the straits open to Russian warships that could be used to threaten Ukraine. However, Kyiv hopes the proposed new Istanbul Canal may be blocked for Russian naval ships since, according to Ukraine, it won’t be governed by the Montreux Convention, which regulates transit through the Turkish Straits.

Both countries have benefited from military cooperation and continue to pursue economic ties, including the proposed free trade deal. Turkey sees Ukraine as a key part of its goal to restore its once overwhelmingly dominant position in the Black Sea, and Ukraine sees Turkey as a counterbalance to Russian influence and leverage in the Black Sea.

Their relationship is driven by their own strategic interests. So long as they need allies in the Black Sea, they will look to each other as strategic partners.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario