Bernie Sanders seems certain to lose the Democratic nomination. But his movement has changed the party

Edward Luce

© Reuters

“The old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”

- Antonio Gramsci, in his prison notebooks, on how societies in flux embrace all kinds of radicalism

Just over a century ago, American socialism hit its high-water mark.

Some might consider that combination of words — “American socialism” — to be an oxymoron. But the US allergy to socialism can be exaggerated. In the local elections of 1917, the Socialist Party of America took a third of the council seats in Chicago, a quarter in New York and large chunks across the industrial Midwest. Millions subscribed to socialist newspapers.

The movement then all but vanished from the American landscape. The scissor effect of Russia’s Bolshevik revolution later that year, and the Socialist party’s opposition to America’s entry into the Great War, cut it to shreds.

Most of its leaders, including the legendary orator Eugene Debs, who had contested five presidential elections, were imprisoned under the hurriedly passed Espionage Act. Neither the party nor its creed recovered in the 20th century. The very word carried a hint of anti-Americanism during the height of the cold war.

It took 99 years for “socialism” to re-enter mainstream America’s lexicon. In the bitterly contested Democratic primaries of 2016, the self-declared socialist Bernie Sanders came close to wresting the nomination from Hillary Clinton. Their differences poisoned the party. Roughly one in eight of Sanders’ supporters voted for Donald Trump that year. Others went for Jill Stein, the Green party candidate. That leakage alone accounts for Clinton’s defeat.

Older generations may recoil at the younger Sanders’ flirtation with the Soviet Union, which has surfaced in his second attempt at the nomination. But the Berlin Wall has now been down for as long as it was up.

Bernie Sanders yesterday told the press he was staying in the race despite setbacks in the latest primaries and was looking forward to Sunday’s debate with rival Joe Biden © Getty Images

Just under half of Americans under the age of 39 have a positive view of socialism, according to Gallup. If, as now seems certain, Sanders fails again to take the crown in 2020, his supporters will be a decisive factor in the contest against Trump.

The party’s likelier nominee, former vice-president Joe Biden, would have one big advantage over Hillary Clinton; knowing which mistakes to avoid. Chief of these is winning the support of the anti-establishment left in November, even if that means adopting part of Sanders’ agenda. Backing a wealth tax on America’s super-rich and embracing a “green new deal” are now very much on the cards.

Most Europeans would use the term “social democrat” rather than socialist to describe policies such as paid sick leave, parental rights and basic universal healthcare. Since the cold war, American opponents of such protections have sought to discredit them with the socialist label.

Under Trump, almost any Democratic policy, however modest, has been demonised as Venezuelan socialism.

As a result, Sanders embraces the word to a fault. Like an itinerant preacher, he has criss-crossed America saying over and over that billionaires and corporations have rigged the system against ordinary people. In spite of Sanders’ crankiness — and partly because of it — he strikes a deep chord with the young, even if many believe elections are also rigged.

Bernie Sanders at a campaign rally last month with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. The 30-year-old congresswoman from New York may now pick up the Vermont senator’s torch © Reuters

Other less stubborn — and perhaps more appealing — characters, such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the 30-year-old congresswoman from New York, may now pick up Sanders’ torch. On whatever terms the senator exits his primary battle with Biden, America’s left is in the throes of an unexpected golden age.

Should we discount this rebirth of US socialism as a “morbid symptom” — a cry of pain from a society entering a new technological age? Or is Sanders the harbinger of a lasting change — a John the Baptist to a future presidential Jesus?

-------------------

I probe that question in one of the least likely places — Marin County in northern California. Nestled between San Francisco and the vineyards of Sonoma and Napa Valley, Marin is one of the most abundant places on earth. At $93,000, the median household income is America’s fifth highest. Hollywood producer George Lucas has a gated ranch here.

You cannot keep count of the Zen retreats, yoga farms and meditation centres dotted throughout its Pacific coast landscape. Yet what happens in California often predicts the future of America. And what happens in Marin — home to the organic food movement as well as the 1960s cult band, the Grateful Dead — often sets the tone for California.

Sanders won the state on Super Tuesday by a margin of seven percentage points. Biden just beat him in Marin, but only because most of its increasingly Hispanic workforce cannot afford to live there. Most of Marin’s nearby counties, including Sonoma, Alameda and even Silicon Valley’s San Mateo, chose Sanders.

Here within San Francisco’s gilded radius lives the soul of liberal America. Perhaps its dirtiest secret is that it is home to the country’s sharpest inequalities. San Francisco boasts more billionaires and more homeless people per capita than any other city in the US.

Marin County, which is just a short drive across the Golden Gate Bridge, is San Francisco’s arcadian backyard. The median home price is $1.2m, which is almost quadruple the national average. Yet the county’s “affordable housing” endowment is only $6.3m, from which it has to leverage an annual budget.

“It’s not even small change,” says Leelee Thomas, Marin County’s elected officer, who has the Sisyphean role of creating rentable accommodation for its less plutocratic residents.

“Currently, our economic system is set up to benefit the wealthy at the top of our system, and crumbs are left for those who are struggling.”

The county hosts far more economically squeezed people than initially meets the eye. Set apart from the roads, you start to glimpse numerous trailer parks, which are mostly manufactured houses. Some of the smaller conventional homes have three or four pick-up trucks outside, an indication that several families are crammed inside.

Soaring housing costs are a constant headache for Marin’s larger employers. One of its biggest is Good Earth Natural Foods, an organic superstore that is the county’s main competitor to Whole Foods. Elsewhere in America, Whole Foods is dubbed “Whole Pay Check” by some, because it is so expensive. Much of it is cheap compared with Good Earth. “People walk out of here with $400 of produce in their carts,” says Al Baylacq, a partner in Good Earth. “If you’re shopping at Good Earth, budget is not your primary concern.”

Baylacq is an avowed Sanders supporter, as are many of his store’s 550 employees, almost half of whom are Hispanic. In contrast to Whole Foods, which is owned by Amazon, the online behemoth, every one of its products is organic. Good Earth believes in sustaining local small businesses.

Al Baylacq, a partner in Good Earth Natural Foods, an organic superstore business, and a Sanders supporter: ‘I have been blessed with some very lucky breaks’ © Janet Delaney

There is a hint of the 1960s psychedelic to Baylacq. He sees his business as a soulful alternative to Amazon’s corporate philosophy. As a self-declared “Dead Head” — an ardent fan of the Grateful Dead, and now of Phish, its closest contemporary — Baylacq’s stakeholder values should come as little surprise.

He takes pride in the fact that Phish come from Sanders’ home state of Vermont. “Amazon sucks up business and destroys independent producers in the most ruthless way,” Baylacq says. “If your product is not listed on Amazon — on their terms — then you may as well declare bankruptcy. I am happy to own my support for Bernie as my resistance to that America.”

I ask whether Baylacq’s employees can afford to shop in the store where they work. He laughs.

“Nowhere close,” he says. Many of them have to commute at least an hour from the endless residential tracts and dormitory towns that serve Marin County and San Francisco. I remind him that Henry Ford famously pledged to pay his workers enough to buy the Model T Fords they were making. That pledge turned into the informal social contract of America’s postwar middle class.

Baylacq started work at 13 as a butcher’s assistant. Now 54, he sits on philanthropic boards. Isn’t his success proof that the American dream is alive and well? “Not really,” he says. “I have been blessed with some very lucky breaks.” He sketches the adult lives of his childhood peers, which do not sound too rosy.

Later I go to Paper Mills, which must be the most blue-collar bar in Marin. There is a crooner twanging his tunes. The women wear their hair long. Many of the men are wearing some kind of hat, most of them cowboy.

Here I meet Andy Giddens, 68, who, by his own definition, falls between hippie and redneck. Marin born and bred, Giddens made his living painting houses. The wealthier the person, the likelier they were to shortchange him, he says.

“Like Trump, they wait till you’ve done the work, then they tell you, ‘There’s something wrong with your work; we’re going to pay you $5,000 less than agreed.’”

Andy Giddens, wearing his ‘Make Siberia Warm Again’ cap, says a lot of his friends in Marin County will only consider voting for Sanders as other Democrats are ‘too establishment’ © Edward Luce

Giddens is wearing what looks at first glance like a Trumpian “Make America Great Again” baseball cap. In fact, it says: “Make Siberia Warm Again.” A lot of Trump supporters, including some of Giddens’ relatives, make the same mistake and greet him as a fellow Trumpian. “Some of them are so goddam dumb,” he says laughing. “I had 200 of these caps made.”

I am swigging a bottle of Corona beer, which prompts dark jokes about the coronavirus. Giddens told me that most of his friends were Bernie supporters. Some voted Trump in 2016, but they have now seen enough.

“I mean, Trump didn’t even know that normal influenza can kill,” he says. “And he calls himself an expert.” A lot of his friends would only consider voting for Bernie, he says. Other Democrats are “too establishment”.

-------------------

Across the Bay Bridge to Berkeley, home to the US’s most liberal campus — and former seat of one of the country’s turn-of-the-century socialist mayors — I visit Robert Reich, who is among America’s leading progressives (“socialism” is not a term he uses). I want to see Reich for two reasons. First, he is an influential supporter of Bernie Sanders. Second, he is one of Bill Clinton’s oldest friends. Almost nobody fits both those descriptions.

When I first lived in the US in the late 1990s, I read Reich’s memoir, Locked in the Cabinet, about his frustrations as Clinton’s first-term Labor secretary. They got to know each other as young Rhodes scholars on a transatlantic passage to Britain in 1968. Reich once went on a date with Hillary Rodham when they were at Yale law school.

Robert Reich, who was Labor secretary under Bill Clinton, is a Sanders backer. ‘I don’t dislike the rich at all,’ he says. ‘But as a group they hang out too much together’ © Getty Images

Robert Reich, who was Labor secretary under Bill Clinton, is a Sanders backer. ‘I don’t dislike the rich at all,’ he says. ‘But as a group they hang out too much together’ © Getty ImagesAs a leading “FOB” (friend of Bill), Reich was a chief architect of Clinton’s 1992 campaign, which promised blue-collar Americans a bridge across the “information superhighway” to the 21st century.

He quickly grew disenchanted with the Clinton White House. People such as Robert Rubin, a former Goldman Sachs partner, and Harvard scholar Lawrence Summers took the administration in a “neoliberal” direction. Alan Greenspan, chair of the Federal Reserve, held far more sway in Clinton’s Washington than the labour unions.

Clinton cut US welfare spending, deregulated finance and expanded tax subsidies for business. “I once said something about ‘corporate welfare’ [a phrase Reich coined] and Rubin said, ‘We can’t denigrate captains of industry,’” recalls Reich. “I realised we had gone from being a party of the working class to a party of the college class. They were in thrall to Wall Street.”

That shift is often personalised as a victory of the Rubin wing over the Reich one. It was dubbed Rubinomics and marked the end of the party that Franklin D Roosevelt had created in the 1930s. Clinton’s third way Democrats paid lip service to FDR and his New Deal, which created America’s modern safety net. But they danced to a very different tune composed by Ronald Reagan in the 1980s.

The Clinton era came amid rapid changes in the US labour market. Median household income had begun to stagnate in the late 1970s. Some of that was cushioned by the rise of two-earner households as women increasingly started work to make up for their husband’s job loss or declining wages.

In contrast to Europe and Canada, America’s female labour force participation rate reached a plateau in the early 2000s. In addition to hiring others to care for their children and working ever-longer hours, blue-collar America’s third “coping mechanism” was to use their homes as piggy banks, by taking out home equity loans from the banks. All that came crashing to a halt with the 2008 financial crisis.

“People woke up to the fact that all their coping mechanisms were exhausted,” says Reich. “Wages weren’t rising, your contractual relationship with your employer was now totally one-sided and bankruptcy protections existed only for the rich. Is it any surprise people have been turning to anti-establishment politicians?”

Protesters calling for more workers’ rights at a May Day rally in New York in 2018. Just under half of Americans aged under 39 have a positive view of socialism, according to Gallup © Getty

Reich’s friendship with the Clintons has cooled somewhat after he endorsed Barack Obama over Hillary in 2008. When Obama was president, the populist backlash erupted in the form of the Tea Party movement on the right, which captured the Republican party, and the Occupy Wall Street movement on the left, which stayed on the margins. Sanders picked up the spirit of the Occupy movement a few years later.

Reich spent a lot of time with voter focus groups during the 2016 election in Midwestern cities such as Toledo, Dayton and Cleveland, which helped make Trump president. What struck him most was the ubiquity of “crossover voters” — people who would vote for Trump or for Sanders, but would never contemplate voting for Clinton. This is how Giddens describes himself, using the term “tweener”. “What tied them was a rejection of the usual faces,” Reich says. “If anything, that sentiment has grown since 2016.”

His old friends the Clintons spent a lot of their summers in the Hamptons with the same old crowds of hedge-fund titans and media moguls. “I don’t dislike the rich at all — this isn’t personal,” he says. “But as a group they hang out too much together.” He calls today’s era the “second gilded age”. The first, in the late-19th century, was also a time of great disruption — railways, electricity and the internal combustion engine. Like today, it was a period of mass immigration.

The legendary orator Eugene Debs, leader of the Socialist Party of America, in 1918. Debs contested five presidential elections but was jailed in 1919 under the Espionage Act © Bettmann Archive

Today’s version of the Carnegies and Rockefellers mostly live 30 or so miles south of Reich’s office in Silicon Valley — and up the west coast in Seattle, home to Microsoft and Amazon. “Monopoly power is less visible today than in the first gilded age but it is just as real,” says Reich. “People know they are being shafted but not always exactly by who.”

----------------

It came as little surprise that Sanders did relatively well this week in Washington State, home to Seattle. Much like in the first gilded age, American socialism is largely a creature of the cities. Immigrants also play a starring role. In the early 20th century, it was largely New York Jewish refugees from Russia, who shared the Bolsheviks’ hatred of the tsar. The other wing was German-speaking incomers to the Midwest, particularly Wisconsin.

One of today’s faces of US socialism is Kshama Sawant, leader of the Socialist Alternative, who is the longest-serving member of Seattle’s city council. It was Sawant, 46, a self-declared Marxist, who started the movement for a $15-an-hour minimum wage. After she pushed it through the Seattle council in 2017, it quickly went national. All Democrats, including Biden and Sanders, now back it as a federal law. Sawant’s main cause today is to pass a tax on Seattle’s big companies, which she has called the Amazon Tax.

Kshama Sawant, a self-described Marxist and long-serving Seattle city councillor, hopes Sanders will run as an independent if he fails to secure the nomination © Cody Cobb

I join Sawant on a chilly day in the large tract of downtown Seattle that has been overtaken by Amazon, which long since dwarfed Microsoft as the city’s largest employer. In a tribute to its huge influence, Amazon is exempt from state and city taxes. In 2019, it paid virtually zero federal taxes either.

Depending on the ups and downs of the equity markets, Amazon is valued at more than a trillion dollars. Jeff Bezos, its founder and chief executive, is personally worth upwards of $120bn.

Sawant is leading a rally next to the Amazon biosphere, an indoor hothouse that serves as an incongruous backdrop to the wintry protest. In the previous 72 hours, Seattle had suddenly emerged as America’s first venue of home-grown coronavirus infections. In spite of unease over the risk of contagion, Sawant’s “Tax Amazon” rally was well attended.

The mood could not be described as conciliatory. “Bezos makes $8.9m an hour. Amazon warehouse workers make $16.75 an hour,” says one relatively informative sign. “No one needs that much f**king money,” says another.

“The rich hate you,” says a third. The most common are “Tax Amazon” and “Housing is a human right.” The banner “Normalize shoplifting” hints at an anarchist element.

Protesters at a ‘Tax Amazon’ march this month in Seattle. In a tribute to Amazon’s huge influence, the company is exempt from state and city taxes © Cody Cobb

Sawant, who has been a warm-up speaker at Sanders’ rallies, sets out the case for taxing Amazon, a company that spent millions of dollars fruitlessly trying to defeat her in her last election two years ago. Washington’s state government, in nearby Olympia, is trying to pass a pre-emption law that would ban Seattle from imposing the tax. The Democrats are the party of billionaires, Sawant says. Socialists are the opposition.

Much like in San Francisco, New York and other Democratic strongholds, the cost of housing in Seattle is prohibitive. A poll of unions showed that rent took up 70 per cent of most members’ income — about twice the level considered to be rent-poor. Proceeds from the Amazon Tax would go on social housing.

Sawant has tried without success to persuade Bezos to hold a public debate with her. “We are always David fighting Goliath,” she tells me after the rally in a nearby Starbucks — another of Seattle’s corporate champions.

The coffee chain’s billionaire founder Howard Schultz briefly flirted last year with running as a self-funded independent for the White House. A fourth corporate native, Boeing, has received $8.7bn in direct subsidies from Washington State. It pays no state tax either. I am reminded of Reich’s talk about corporate welfare.

I want to know what drove Sawant to become America’s most visible elected Marxist. Born in Pune, India, and raised in Mumbai, Sawant studied economics in North Carolina before becoming a software engineer at Nortel, the Canadian telecoms company.

Then she moved to Seattle where she found religion in the form of Karl Marx. One to one, Sawant is polite and gently spoken in contrast to her tone from the podium. I am told her ubiquitous gallery of supporters often helps cajole Seattle’s nine-person council into doing her bidding.

Apart from the minimum wage, she has passed paid and sick leave rights, structured work hours and other rights that in the past would have been negotiated by unions. Amazon, like almost all of America’s tech economy, is a union-free company. “As a socialist I find it quite difficult to talk about my history,” says Sawant. “We don’t like to dwell too much on personal stuff.” She retains $40,000 of her $140,000 councillor’s salary and gives the rest to a strike fund.

Sawant becomes animated when I raise Sanders’ battle with Biden. In 2016, she refused to vote for Clinton. Would she do the same this year if Sanders failed to take the nomination? “I would hope Bernie would run as an independent,” she replies. Either way, Sawant is planning to lead a big demonstration in Milwaukee, where the Democratic convention will be held in July. Regardless of circumstance, they will agitate for Sanders to be the nominee. She calls it “#million2milwaukee”.

After New York, Milwaukee was the leading hotbed of American socialism in the early 1900s. I find it hard to believe she could attract anywhere near a million. What, I ask, if you called a revolution and nobody showed up, in paraphrase of the 1960s anti-war slogan? “We have to take the fight to them,” she says. “If we thought like that we would never have passed the minimum wage.” Sawant puts great faith in the role of young voters, who are not “burdened with the baggage of history”.

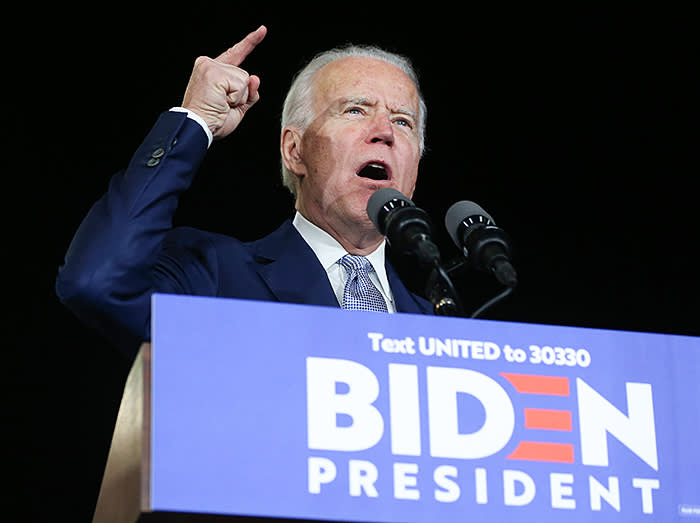

Joe Biden, who is now the clear favourite to win the Democratic nomination, on the campaign trail in Los Angeles this month © Getty

A few days after I met Sawant, Sanders hit what in retrospect was clearly his Waterloo in the Super Tuesday primary. Biden won 10 of the 14 states and took what could quite rapidly turn into a prohibitive lead in the delegate count. Sanders has argued that he, and he alone, can bring out the young in droves to defeat Trump in November.

In addition, only he can appeal to Reich’s crossover Trump voters. His first theory was badly dented by the voter surge in states that Biden won heavily, such as Virginia, and the anaemic millennial showing in Sanders strongholds, including his own state of Vermont.

I had caught a foretaste of this in Seattle when I spoke to Stephen Nicholson, a student at Evergreen State College in Washington State. Nicholson is a strong Bernie supporter. Most of his student peers are too. Are they all planning to vote? “A lot of my friends are cynical and probably won’t bother,” he admits. “They think the system is rigged whatever they do.” That mindset is rife among “Bernie bros” in the days after Super Tuesday. “The fix is in” trended on Twitter.

So, too, is the idea that the Democratic elites had somehow finagled the Biden campaign’s recovery from the near dead. In reality, it was African-American voters who turned the tide in South Carolina on the weekend before Super Tuesday. The establishment did not choose Biden — though it rushed to join his bandwagon; he was saved by the southern black voter.

------------------

The hip Berkeley restaurant Chez Panisse, which gave birth to the “slow-food” movement in 1971, is not an obvious place to shoot the breeze about the future of American socialism. The venue is not my idea. Jerry Brown, the sprightly 81-year-old former four-time governor of California, thought it was an ideal location to discuss the subject.

We are briefly joined by Alice Waters, who founded Chez Panisse and is feted as the inventor of modern American cuisine. Brown and Waters — two legends of 20th-century California — embrace like siblings.

I ask Waters, now 75, whether a new social revolution is afoot. This is shortly before Sanders’ California win. “America is suffering from two great problems,” says Waters. “The first is the meaninglessness of work. So many people have soul-destroying jobs. The other is loneliness. You see it everywhere you look. Communities have broken down.” Brown nods in agreement. “Didn’t you promise me a communal housing experiment for old people when you were governor?” Waters asks Brown. “Something like that,” he replies. “We’re still waiting,” she says.

Former four-time California governor Jerry Brown: ‘In much less disruptive times than today, politics is hard to predict’ © Janet Delaney

In an interview many years ago, Brown was the first American politician I have met — and so far the last — to have quoted Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Marxist. Having talked bleakly about America’s future, California’s then governor said he followed the Italian’s dictum:

“Pessimism of the intellect: optimism of the will.”

Gramsci wrote the line about morbid symptoms surfacing when a society is in flux. It struck me that the combination of Trump and a coronavirus epidemic would be a fairly compelling sign of that. Brown agrees.

But he hesitates to pronounce a verdict on Sanders.

The two are about the same age. Brown’s views have evolved over the decades. He made the time-honoured journey from idealism to pragmatism. Sanders’ views have barely shifted. Has history caught up with Sanders? Or is it passing him by?

Brown, who in his younger days was known as Governor Moonbeam — a hippie-era term — hedges his bets. Socialism is not his thing. “In much less disruptive times than today, politics is hard to predict,” Brown says. “Very unusual things can happen.” His pessimism is hard to miss.

Given his very different style of politics, Brown’s reluctance to predict is striking. I think about what Reich had told me. He said centrist Democrats were panicking that their party was drifting into “another 1972” — the year George McGovern, the leftwing Democratic nominee, lost in a landslide to Richard Nixon. Sanders was the new McGovern, in their view.

What haunted Reich was 1968, not 1972. That was the year Democrats nominated Hubert Humphrey, the vice-president and pillar of the establishment. He was also defeated by Nixon. In Reich’s view, Biden is the new Humphrey. It is a tribute to Brown’s ambivalence that both those years are imaginable in today’s America — and neither.

With or without Sanders, Democrats are moving steadily to the left. Even before any putative deal with Sanders to unite the party, Biden’s platform is considerably to the left of his days in the Obama administration. The party of Clinton and even Obama is fading.

Among others, Robert Rubin — the man who lent his name to Rubinomics — no longer objects to a wealth tax. Few would have predicted that. Even when Sanders is losing, he is winning.

Edward Luce is the FT’s US national editor

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario