by: Lance Roberts

Summary

- Over the last decade, the Federal Reserve has kept rates at extremely low levels, and flooded the system with liquidity, which did not have the effect of fostering either economic growth or inflation to any significant degree.

- The trouble currently is that global short-term interest rates are still close to, or below zero, and cannot be cut much more, which has deprived central banks of their main lever if a recession strikes.

- The biggest challenge the Fed faces currently is how to deal with a recession. While the Fed talks about wanting higher rates of inflation, it can't run the risk that rates will rise.

- The trouble currently is that global short-term interest rates are still close to, or below zero, and cannot be cut much more, which has deprived central banks of their main lever if a recession strikes.

- The biggest challenge the Fed faces currently is how to deal with a recession. While the Fed talks about wanting higher rates of inflation, it can't run the risk that rates will rise.

"If the U.S. economy entered a recession soon and interest rates fell in line with levels seen during the moderate recessions of 1990 and 2001, yields on even longer-dated Treasury securities could fall to or below zero."

- Senior Fed Economist, Michael Kiley - January 20, 2020

I was emailed this article no less than twenty times within a few hours of it hitting the press. Of course, this was not a surprise to us. To wit:

"Outside of other events such as the S&L Crisis, Asian Contagion, Long-Term Capital Management, etc. which all drove money out of stocks and into bonds pushing rates lower, recessionary environments are especially prone at suppressing rates further. Given the current low level of interest rates, the next recessionary bout in the economy will very likely see rates near zero."

That article was written more than 3 years ago in August 2016.

Of course, three years ago, as the "Bond Gurus," like Jeff Gundlach and Bill Gross, were flooding the media with talk about how the "bond bull market was dead" and "interest rates were going to rise to 4%, or more," I repeatedly penned why this could not, and would not, be the case.

While it seemed a laughable concept at the time, particularly as the Fed was preparing to hike rates and reduce their balance sheet, the critical aspect of leverage was overlooked.

"There is an assumption that because interest rates are low, that the bond bull market has come to its inevitable conclusion. The problem with this assumption is three-fold:

- All interest rates are relative. With more than $10-Trillion in debt globally sporting negative interest rates, the assumption that rates in the U.S. are about to spike higher is likely wrong. Higher yields in U.S. debt attracts flows of capital from countries with negative yields, which pushes rates lower in the U.S. Given the current push by Central Banks globally to suppress interest rates to keep nascent economic growth going, an eventual zero-yield on U.S. debt is not unrealistic.

- The coming budget deficit balloon. Given the lack of fiscal policy controls in Washington, and promises of continued largesse in the future, the budget deficit is set to swell above $1 Trillion in coming years. This will require more government bond issuance to fund future expenditures, which will be magnified during the next recessionary spat as tax revenue falls.

- Central Banks will continue to be a buyer of bonds to maintain the current status quo, but will become more aggressive buyers during the next recession. The next QE program by the Fed to offset the next economic recession will likely be $2-4 Trillion which will push the 10-year yield towards zero."

Of course, since the penning of that article, let's take a look at where we currently stand:

- Negative yielding debt surged past $17 trillion, pushing more dollars into positive-yielding U.S. Treasuries, which led to rates hitting decade lows in 2019.

- The budget deficit has indeed swelled to $1 trillion and will exceed that mark in 2020 as unbridled government largesse continues to run amok in Washington.

- The Federal Reserve, following a very short period of trying to hike rates and reduce the bloated balance sheet, completely reversed the policy stance by cutting rates and flooding the system with liquidity by ramping up bond purchases.

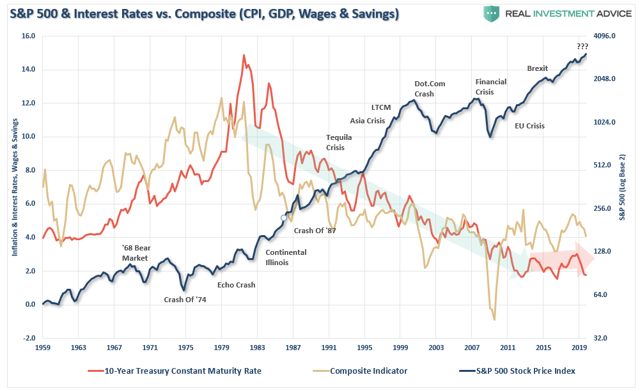

The biggest challenge the Fed faces currently is how to deal with a recession. Given the current expansion is the longest on record; a downturn at some point is inevitable. Over the last decade, as shown in the chart below, the Federal Reserve has kept rates at extremely low levels, and flooded the system with liquidity, which did not have the effect of fostering either economic growth or inflation to any significant degree. (As noted, the composite index is of inflation, GDP, wages, and savings, which has closely tracked the long-term trend of interest rates.)

Naturally, at any point monetary accommodation is removed, an economic and market downturn is almost immediate. This is why it is feared central banks do not have enough tools to fight the next recession.

During and after the financial crisis, they responded with a mixture of conventional interest rate cuts and, when these reached their limit, with experimental measures, such as bond buying ("quantitative easing", or QE) and making promises about future policy ("forward guidance").

The trouble currently is that global short-term interest rates are still close to, or below zero, and cannot be cut much more, which has deprived central banks of their main lever if a recession strikes.

The Fed Is Trapped

While the Fed talks about wanting higher rates of inflation, as shown above, it can't run the risk that rates will rise. Simply, in an economy that requires $5 of debt to create $1 of economic growth, the leverage ratio requires rates to remain low or "bad things" happen economically.

1) The Federal Reserve has been buying bonds for the last 10 years in an attempt to keep interest rates suppressed to support the economy.

The recovery in economic growth is still dependent on massive levels of domestic and global interventions.

Sharply rising rates will immediately curtail that growth as rising borrowing costs slows consumption.

2) Rising interest rates immediately slows the housing market, taking that small contribution to the economy away. People buy payments, not houses, and rising rates mean higher payments.

3) An increase in interest rates means higher borrowing costs, which leads to lower profit margins for corporations. This will negatively impact the stock market given that a bulk of the "share buybacks" have been completed through the issuance of debt.

4) One of the main arguments of stock bulls over the last 10 years has been the stocks are cheap based on low interest rates. When rates rise, the market becomes overvalued very quickly.

5) The massive derivatives market will be negatively impacted, leading to another potential credit crisis as interest rate spread derivatives go bust.

6) As rates increase, so does the variable rate interest payments on credit cards.

With the consumer being impacted by stagnant wages, higher credit card payments will lead to a rapid contraction in disposable income and rising defaults.

7) Rising defaults on debt service will negatively impact banks, which are still not adequately capitalized and still burdened by large levels of risky debt.

8) Commodities, which are very sensitive to the direction and strength of the global economy, will plunge in price as recession sets in. (Such may already be underway.)

9) The deficit/GDP ratio will begin to soar as borrowing costs rise sharply. The many forecasts for lower future deficits have already crumbled as the deficits have already surged to $1 Trillion and will continue to climb.

10) Rising interest rates will negatively impact already massively underfunded pension plans leading to insecurity about the ability to meet future obligations.

With a $7 Trillion funding gap, a "run" on the pension system becomes a high probability.

I could go on, but you get the idea.

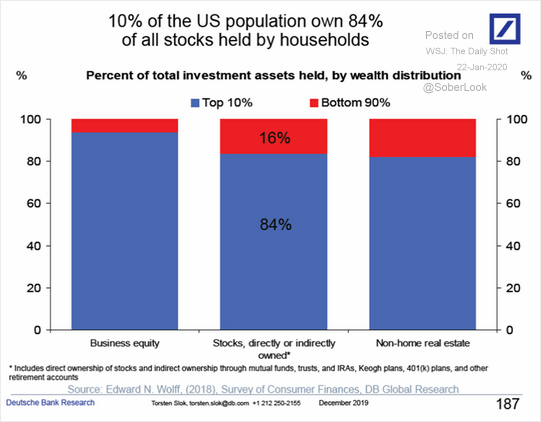

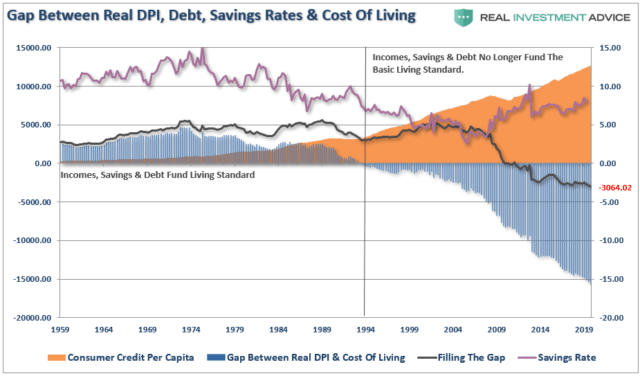

The issue of rising borrowing costs spreads through the entire financial ecosystem like a virus. The rise and fall of stock prices have very little to do with the average American and their participation in the domestic economy. This is because the vast majority of Americans are living paycheck to paycheck.

However, since average Americans require roughly $3000 in debt annually to maintain their standard of living, interest rates are an entirely different matter.

As I noted last week, this is a problem too large for the Fed to bail out, which is why it is terrified of an economic downturn.

The Fed's Endgame

The ability of the Fed to use monetary policy to combat recessions is at an end. A recent article by the WSJ agrees with our assessment above.

"In many countries, interest rates are so low, even negative, that central banks can't lower them further. Tepid economic growth and low inflation mean they can't raise rates, either.

Since World War II, every recovery was ushered in with lower rates as the Fed moved to stimulate growth. Every recession was preceded by higher interest rates as the Fed sought to contain inflation.

But with interest rates now stuck around zero, central banks are left without their principal lever over the business cycle. The eurozone economy is stalling, but the European Central Bank, having cut rates below zero, can't or won't do more. Since 2008, Japan has had three recessions with the Bank of Japan, having set rates around zero, largely confined to the sidelines.

The U.S. might not be far behind. 'We are one recession away from joining Europe and Japan in the monetary black hole of zero rates and no prospect of escape,' said Harvard University economist Larry Summers. The Fed typically cuts short-term interest rates by 5 percentage points in a recession, he said, yet that is impossible now with rates below 2%."

This too sounds familiar, as it is something we wrote in 2017 prior to the passage of the tax reform bill:

"The reality is that the U.S. is now caught in the same liquidity trap as Japan. With the current economic recovery already pushing the long end of the economic cycle, the risk is rising that the next economic downturn is closer than not. The danger is that the Federal Reserve is now potentially trapped with an inability to use monetary policy tools to offset the next economic decline when it occurs.

This is the same problem that Japan has wrestled with for the last 20 years. While Japan has entered into an unprecedented stimulus program (on a relative basis twice as large as the U.S. on an economy 1/3 the size) there is no guarantee that such a program will result in the desired effect of pulling the Japanese economy out of its 30-year deflationary cycle. The problems that face Japan are similar to what we are currently witnessing in the U.S.:

- A decline in savings rates to extremely low levels which depletes productive investments

- An aging demographic that is top heavy and drawing on social benefits at an advancing rate.

- A heavily indebted economy with debt/GDP ratios above 100%.

- A decline in exports due to a weak global economic environment.

- Slowing domestic economic growth rates.

- An underemployed younger demographic.

- An inelastic supply-demand curve.

- Weak industrial production.

- Dependence on productivity increases to offset reduced employment.

The lynchpin to Japan, and the U.S., remains demographics and interest rates. As the aging population grows becoming a net drag on "savings," the dependency on the "social welfare net" will continue to expand. The "pension problem" is only the tip of the iceberg."

It's good news the WSJ, and mainstream economists, are finally catching up to analysis we have been producing over the last several years.

The only problem is that it is likely too little, too late.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario