Tech Wars Are Complicated and Hard to Win

By: Phillip Orchard

The U.S. campaign to isolate Huawei isn’t quite going according to plan.

Last week, the U.K. and the EU both defied U.S. pressure by sparing the Chinese telecom giant and its state-owned counterpart, ZTE, from a blanket ban on “high-risk suppliers” of 5G gear.

A week earlier, the Pentagon reportedly blocked a plan by the Commerce Department to expand a ban on sales of critical components to Chinese high-tech sectors, citing the potential costs to the United States’ own tech sector.

The gradual decoupling of the U.S. and Chinese tech spheres isn’t petering out; escalation on a number of fronts – scrutiny of Chinese investment, restrictions on R&D collaboration and Chinese immigration, and U.S. diplomatic efforts to isolate China – is still likely.

But January’s developments underscore the inherent difficulty of eliminating the risks of U.S.-Chinese interdependence without doing more harm than good to U.S. interests, not to mention the interests of the friends and allies the U.S. is urging to follow suit.

Containing Huawei vs. Killing Huawei

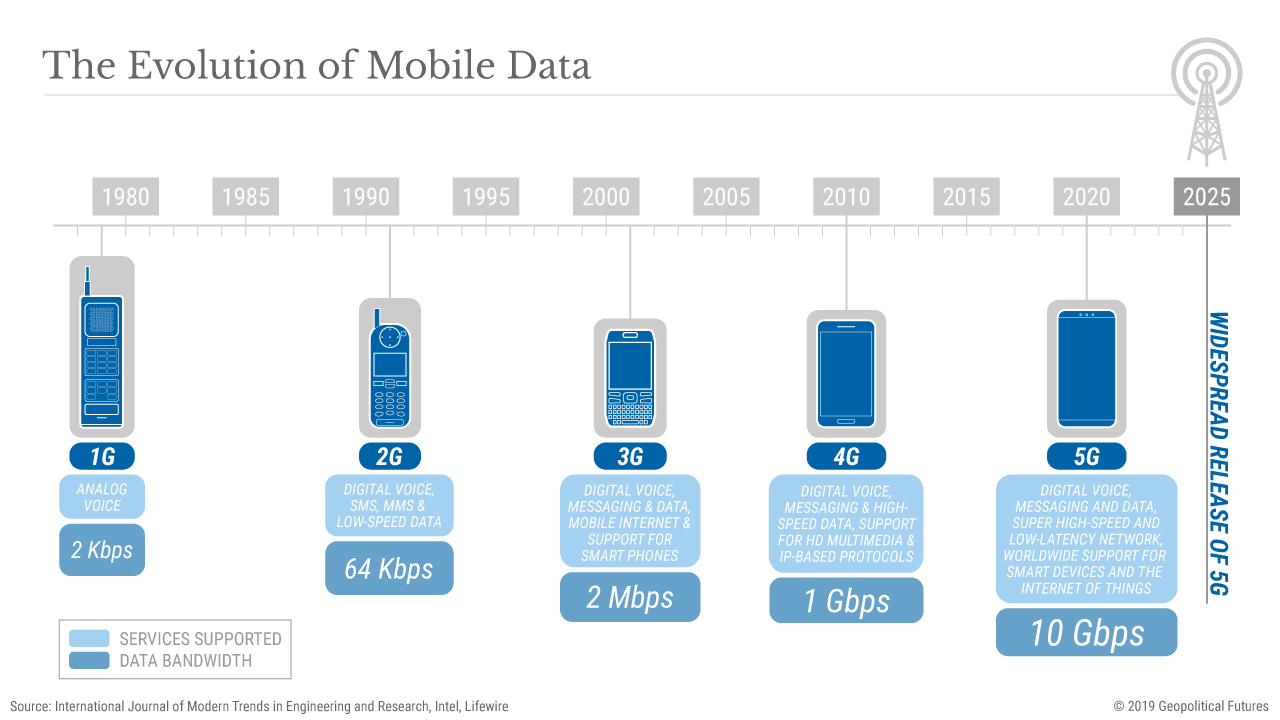

Next-generation cellular and satellite communications technologies will have the potential to unleash a vast new ecosystem of interconnected devices that can reliably transfer deeper oceans of data between them at incredible speeds. Achieving its potential will require a massive and costly expansion of network infrastructure such as base stations, towers and antennas.

The potential economic rewards are sky high, but so too are the potential cybersecurity vulnerabilities, the benefits of being able to exploit them and the rewards of becoming a dominant supplier of network gear.

In other words, if Huawei or ZTE were to insert near-undetectable backdoors into a network’s source code, Chinese state-backed hackers could have easy access to incalculably valuable flows of data – and, potentially, a capability to shut down critical networks altogether. If the world becomes overly dependent on Chinese vendors, Beijing would have an awful lot of bargaining power.

The scale and nature of the risks and rewards won’t become clear for years, and both could fall far short of the hype. But given how much time and how many resources it will take for these systems to be built, along with the potential economic risks of falling behind, governments are having to make critical decisions now to leverage the benefits and protect against worst-case scenarios, including how to manage risks associated with doing business with Huawei.

The U.S. has effectively banned U.S. operators from using Huawei and ZTE equipment in their next-generation cellular networks. But U.S. interests are global. Washington shares intelligence with myriad partners. U.S. troop deployments and military logistics networks cover hundreds of countries.

U.S. multinational corporations move lucrative intellectual property around supply chains throughout the world. Washington thus isn’t content merely to keep Huawei gear away from U.S. shores; it also wants to keep Huawei away from anywhere U.S. interests would be at risk if dependent on Chinese information and communication technology infrastructure.

It can try to do this in two basic ways: by using its diplomatic power to shrink Huawei’s market access and/or by crippling Huawei directly.

Toward the first, the U.S. has been urging friends and allies to ban Huawei from their own 5G build outs – and threatening to withhold intelligence and military cooperation if they don’t. But this campaign has borne little fruit, primarily because of Huawei’s cost advantages, the fear of retaliation from Beijing and the inherent difficulty of proving that Chinese vendors are really so much more threatening than any others. (The biggest cybersecurity challenges facing 5G have little to do with any specific vendor.)

As a result, only Australia and a handful of other countries have imposed formal or de facto bans on Chinese vendors. Most governments are looking for ways to split the difference, welcoming Huawei but also limiting where and how much of its gear can be used. That the U.K. – America’s closest ally and a fellow Five Eyes member – defied Washington in this way will likely embolden others, to varying degrees, to do the same.

The U.S. has therefore also been looking for ways to take aim at Huawei unilaterally. In early 2019, the White House reportedly considered cutting off Huawei’s access to the U.S banking system, making it effectively impossible for the firm to complete transactions in U.S. dollars.

But it decided against it out of fear that it would grind the global financial system to a halt. So instead, the Trump administration started taking steps to starve Huawei of critical components sourced overwhelmingly from U.S. firms, particularly semiconductors, software and chip design.

But this too sparked a backlash – this time from inside the U.S. For example, U.S. chipmakers, who rely on sales to China for an estimated 10-30 percent of their revenue, warned that the loss of sales would cripple their R&D programs and capacity to innovate. A ban could also lead to an irrecoverable loss of market share for foreign chipmakers or, worse, accelerate China's well-funded drive to build a competitive semiconductor industry of its own.

After all, the main reason Chinese firms have struggled to make the leap in sectors like semiconductors is that it simply made more sense to keep buying from the U.S. and focus their resources on what they’re actually good at (or on serving Beijing’s political and diplomatic goals).

U.S. multinational firms, moreover, immediately began exploiting loopholes in the soft ban on sales to Huawei and made clear the overwhelming incentives to find ways to continue selling to China – even if it requires moving operations overseas.

Still, the Commerce Department was reportedly poised to expand the ban on sales until the Pentagon stepped in, arguing that the hit to U.S. tech sector R&D would undermine the U.S. military’s technological edge over China. The Pentagon could still be overruled, and the export ban allowed to go forward.

But it’s clear that the U.S. is having to decide between two largely divergent paths forward: one focused mainly on impeding China’s growth and one that trusts in the U.S.’ ability to simply out-compete China.

Flying Blind

This illustrates just how messy and fraught with unintentional consequences the U.S.-China tech war will be even for Washington, to say nothing of countries caught in the middle.

Consider all the factors at play: On the one hand, there's the theoretical intelligence, commercial and sabotage risks that come with potentially handing Beijing the keys to the castle, the strategic risks of empowering China’s technological rise and fostering global dependence on its goods and goodwill, and the potential loss of vital military or intel support from the U.S.

On the other are immediate cost considerations. For 5G to reach its potential, it will require a staggering amount of capital expenditures. There are only five major end-to-end 5G vendors (none of them American).

Banning Chinese firms would eliminate the two cheapest options and give the remaining three (Finland's Nokia, Sweden’s Ericsson, and South Korea’s Samsung) excessive pricing power. (As it happens, including multiple vendors in network infrastructure is also key to ensuring network resiliency.)

For countries, like the U.K., that would have to rip out Huawei gear from their existing 4G networks, the bill would be even steeper. Higher costs inevitably mean slower implementation, potentially depriving local industries of the chance to reap first-mover advantages and putting them at a disadvantage against foreign competition.

It would also risk provoking Chinese retaliation; Beijing’s threat to cut off market access to German automakers is at the center of the debate in Berlin, for example. (This is all in addition to the aforementioned hit to local companies that supply Huawei and ZTE.)

Each country’s cost-benefit formula will be different. It’s not surprising that Japan, Vietnam and Australia, which see the People’s Liberation Army just over the horizon, are acting more forcefully against Huawei than countries like the U.K. and Germany, whose concerns and hopes regarding China are primarily commercial.

In a great power competition, the interests of third parties rarely align neatly with one side or the other, so there are incentives to play both off each other where possible, keep their options open and otherwise stay out of the cross-fire.

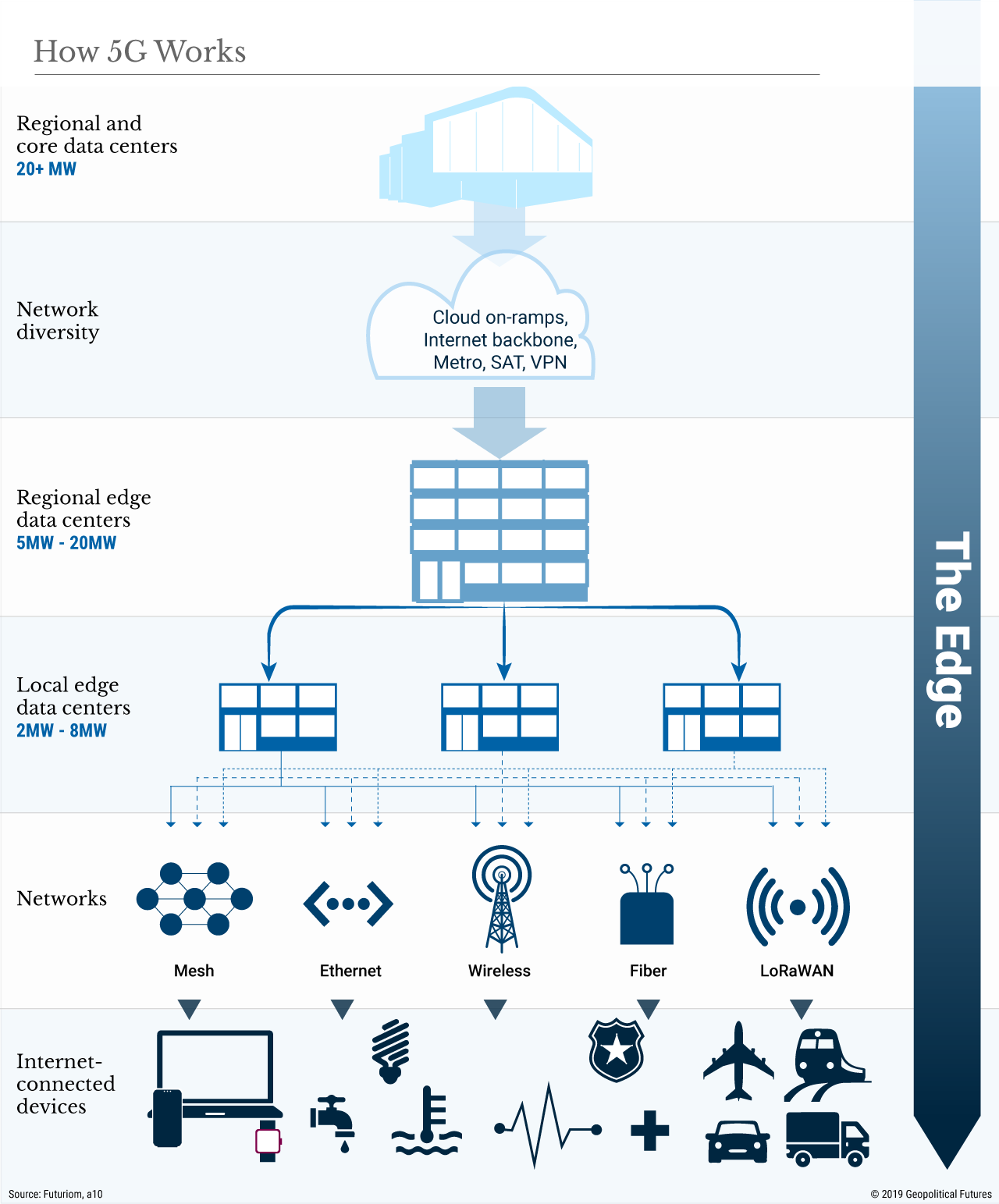

Notably, the U.K. has provided something of a template for how to split the difference between China and the U.S. In short, the U.K. is limiting “high-risk suppliers” of 5G (read: Huawei and ZTE) to what’s known as the edge of the network – think towers and antennas – while barring them from “the core,” where critical functions like authentication and encryption take place.

The U.K. is also capping their market share and barring their gear from networks around military bases and other sensitive installations.

This has not satisfied the U.S., where the Senate is debating legislation that would formally ban intelligence-sharing with countries that use Huawei. (Notably, though, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo moved quickly to downplay the impact of London’s decision on the U.K.-U.S. “special relationship.”)

Critics of the partial ban (on both sides of the Atlantic) argue that the distinction between the core and the edge will erode over time, since 5G won’t live up to its potential unless core functions are pushed out the edge.

The U.K. makes a strong case that the system can be designed in a way to preserve the distinction – and that its system includes enough protections to allow the U.S. to conclude that breaking off intelligence-sharing over it would be counterproductive.

The debate won’t be resolved anytime soon because the rapid evolution of the risks and rewards of 5G technology and applications won’t stop anytime soon. And that’s the crux of the issue: The U.S., its friends and its foes are all scrambling to secure their interests through pivotal policy decisions based on best guesses and worst fears about how the world might look more than a decade from now.

Given the pace of technological change these days, that’s an eternity.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario