Some of the trade war’s aims were accomplished, but many weren’t

By Nathaniel Taplin

Two years, innumerable late-night tweets and reams of newspaper articles later, the U.S.-China trade battle royale of 2018 and 2019 is winding down. A few of its purported aims were accomplished. Many weren’t.

The most lasting impact is a marked, rapid deterioration in Sino-U.S. relations overall. Overt trade hostilities might remain on hold for now as the U.S. election season approaches, but technological, security and ideological competition, always undercurrents to Sino-U.S. relations, have been supercharged by the bitter conflict.

Investors will be dealing with the consequences for years to come as economic “decoupling” raises costs, cooperation on issues like carbon emissions becomes harder, the risk of military conflict in Asia rises and technology buyers increasingly need to choose between competing U.S. and Chinese systems and standards.

The deal itself is both less and more than it appears. Most tariffs will remain in place for now. U.S. exporters, mainly farmers, will gain, to an extent, from big additional Chinese purchases.

But trying to fix a country’s overall trade deficit by focusing on just one partner is a lot like trying to fix a very leaky dike with one finger. China can buy a lot more U.S.-produced pork or manufactured goods, but that will push up U.S. prices, making such goods less attractive at home and in other markets abroad. That means more exports to China, but probably far less to other places and, in some cases, offsetting imports.

President Donald Trump, right, speaks before signing a trade agreement with Chinese Vice Premier Liu He at the White House, Wednesday. Photo: Evan Vucci/Associated Press

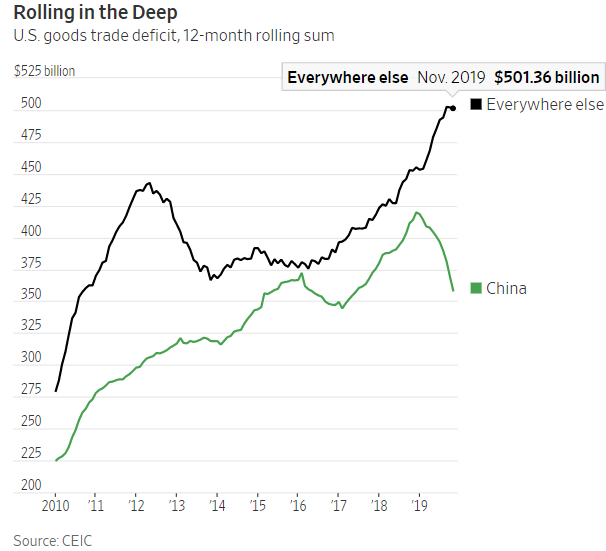

The way targeting China worked out last year illustrates this well. In the 12 months ended in November 2019, the U.S. deficit with China was $56 billion lower than in the 12 months ended in November 2018, data from CEIC shows. But the deficit with the rest of the world rose $49 billion, offsetting nearly 90% of that drop.

The overall U.S. goods deficit only dropped $7 billion, and much of this was due to a falling bill from net oil imports. The biggest near-term impact of the deal is simply removing some of the pernicious uncertainty created by the trade conflict itself.

And the conflict is far from over.

Even as negotiators sign off on the trade deal, Washington is considering measures to further restrict sales of U.S. equipment to Chinese 5G telecommunications champion Huawei and boost federal funding for U.S. 5G research. As the trade fracas has dragged on, it has metastasized into a broader deterioration in relations.

Some aspects of the U.S.’s more combative stance—condemning human-rights abuses and Beijing’s attempts to silence critics or spread disinformation overseas—are overdue and welcome. Others, such as efforts to restrict U.S. semiconductor sales, risk backfiring as U.S. firms lose revenue or shift production abroad.

One thing the trade conflict has noticeably failed to accomplish is any serious commitment from Beijing to abandon its own state-led industrial policy. Instead, China’s leaders have received the message that the U.S. doesn’t welcome its technological rise—and redoubled their determination to promote domestic champions.

Deteriorating relations have spilled over into the security realm as well, most obviously with the Trump Administration’s designation of China as a strategic competitor and statements by top U.S. officials warning of a “clash of civilizations.” Tariffs now in place look unlikely to be scaled back substantially.

That means economic decoupling will continue—just as China’s military is nearing the point where it could plausibly prevail in conflicts near China’s periphery. The risk of mistakes and miscalculations is rising at the same time economic interests in avoiding confrontation are disengaging.

Investors are used to thinking of the Middle East as the real hot spot for political risk. Over the next decade, it seems increasingly likely to be Asia.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario