The company is an emblem of resistance to corporate governance reform

Leo Lewis

© Ingram Pinn/Financial Times

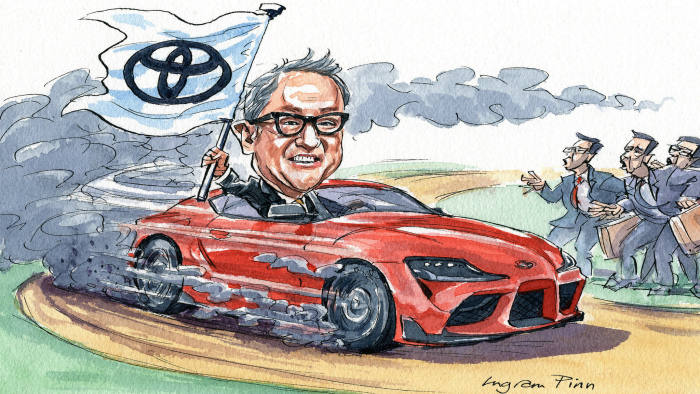

A video on the Toyota Times website shows the automaker’s president at the controls of the GR Supra sports car.

Akio Toyoda emits a boy-racer cackle before skidding the vehicle into an arc of smoking rubber. “I love cars that make a racket and reek of petrol,” he yells.

Jarring for a company whose flagship is the Prius hybrid, whose environmental ambitions outpace most of the global industry’s and whose looming challenge is to usher Japan’s most important company out of the human-controlled, combustion-engine era and into whatever artificially intelligent cleanliness replaces that.

But of course, Toyota gets away with the paradox. Mr Toyoda has an awful lot of conventional motors to shift before the future arrives. His hands-on-the-wheel zeal is a calculated salesmanship Toyota has mastered along with operational excellence, Scrooge-like cost-cutting and defiance of prevailing market headwinds.

It is, after all, a company that has grown sales in a slowing China, expanded profits in a shrinking US market and is on course to sell nearly 11m vehicles worldwide in its current financial year as many of its rivals sputter. But might all this excellence come at a heavy cost?

For years, these qualities have given Toyota a convincing claim to the title of Japan’s greatest company. Jesper Koll of asset manager Wisdom Tree calculates that Toyota, plus its supply chain, sales presence and web of other businesses accounts for up to 8 per cent of Japan’s gross domestic product. It has thrived handsomely on the credo — to echo former US defence secretary Charles Wilson’s 1953 observation on General Motors — that what is good for Toyota is good for Japan.

Investors, led by those who view governance as the defining metric of the age, increasingly question whether this holds true. Some, who see Japan risking insularity with toughened new rules on foreign investment, believe the state’s instinct to protect Toyota may have played a role in forming that policy.

Its dominance creates two related issues.

The first, that Toyota is treated as an exemplar by the rest of corporate Japan, the second is that its huge economic and societal footprint obscures just how much of an exception it is.

Japan would love to believe its corporate sector comprises thousands of mini-Toyotas, but it does not. Toyota’s success promotes the idea that a traditional Japanese governance model works perfectly and allows the intransigent and the incompetent to claim it as a recipe.

This might not matter except that, in an era in which corporate Japan has seemed more susceptible to shareholder engagement and governance improvements, and where foreigners are the swing buyer of Japanese equities, Toyota is a beacon — both of resistance to change and to the idea that Japanese companies are owed protection from the outside world.

It also misses the point of investors’ frustration: the push for better governance is not, for the most part, an attack on corporate Japan, but stems from a conviction that in a market where about half of companies are trading below book value, governance improvements would have a more explosive upwards effect on valuations here than they would almost anywhere else in the world. Toyota may not need that boost, but most others do.

The central complaint is with the company’s addiction to so-called cross-shareholdings — the networks of shares that allegiant Japanese companies hold in one another for reasons other than pure investment. To investors, these portfolios are the glue that hold bad governance in place across corporate Japan. They tie up capital to no purpose, are a form of stealth takeover defence and, in the words of Mizuho chief strategist Masatoshi Kikuchi, “a hindrance to open innovation”.

It is no coincidence that, in the government’s efforts to make the Japanese stock market more attractive to domestic investors, the revised 2018 governance code attempted to compel companies to justify their crossholdings and demanded they not “hinder the sale of cross-held shares by implying a possible reduction of business transactions”.

Toyota, which holds shares in 146 listed companies, whose stock is cross-held by around 112 companies, and which has mastered the art of vague justification, provides unspoken market leadership against this effort.

In recent years, it has inked a series of partnerships with Suzuki, Subaru, Mazda and others. In each case, it has not only bought shares in the partner, but encouraged those partners to buy shares in Toyota.

Toyota was seen to be protecting the smaller companies, but as the auto industry prepares for disruption and the certainty of consolidation, it was actually ringfencing itself. In imitation, significant numbers of Japanese companies also expanded their cross-shareholdings last year.

The risk centres on Mr Toyoda, who is widely rumoured to be on the point of swapping his GR Supra for a more highly-powered vehicle: an ascent to both the chairmanship of Toyota and of the formidable Keidanren business federation.

Japan, teetering so tantalisingly on the brink of a real governance breakthrough, may now be hauled back by the old saw that what is good for Toyota is good for the country.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario