By: Hilal Khashan

When the United Arab Emirates formed in 1971, its first president, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, ruler of Abu Dhabi, the most significant and wealthiest constituent emirate, wanted a neutral and low-profile foreign policy, one that championed pan-Arabism and pan-Islamism.

Things haven’t quite worked out that way.

Not only did the UAE’s mere existence rankle Saudi Arabia, which sees itself as the de facto leader of Sunni Arabs in the Middle East and so tried to stop it from forming, but Riyadh also foiled Abu Dhabi’s efforts to include Qatar and Bahrain in its fledgling nation.

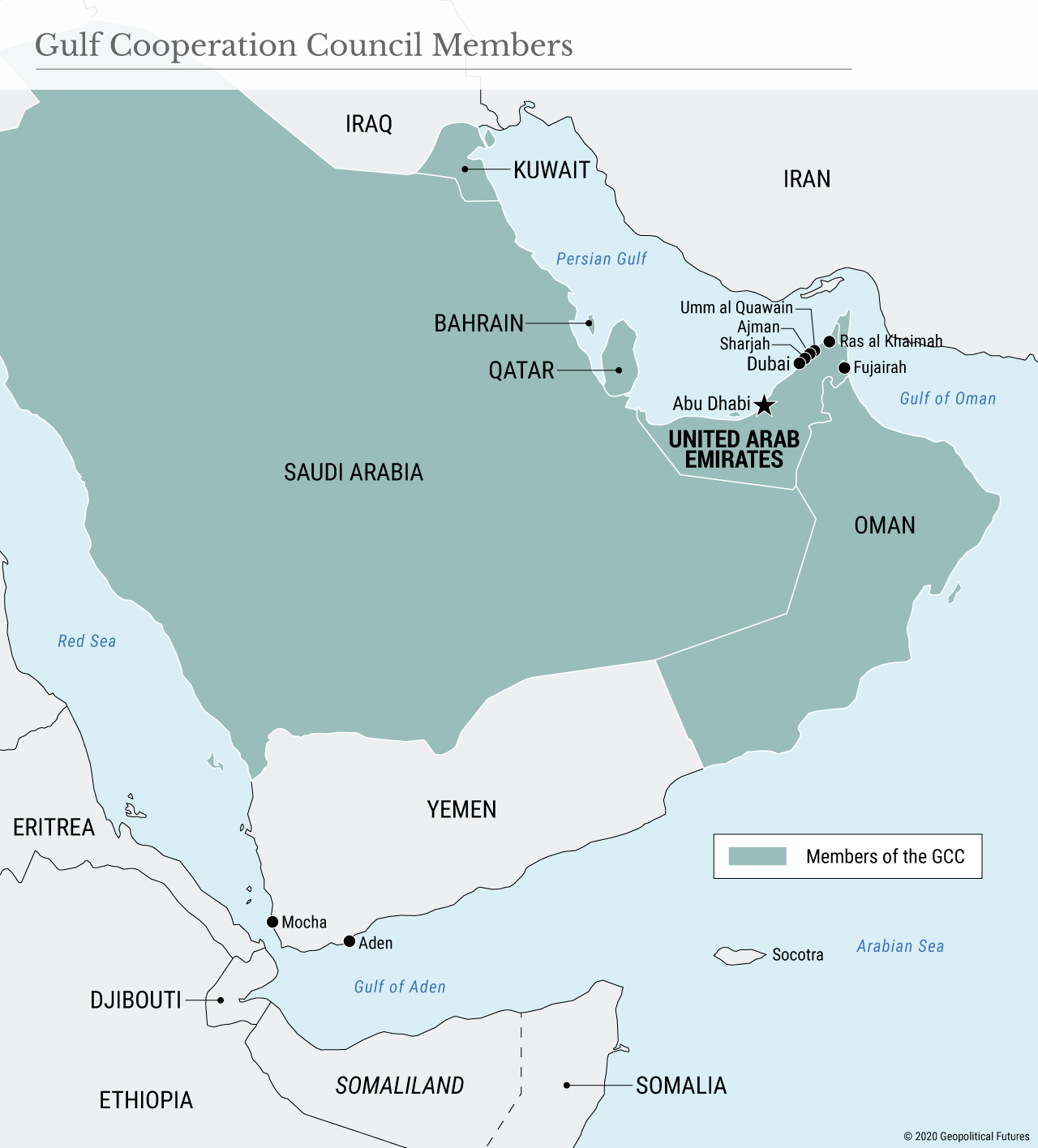

Even after the creation of the Gulf Cooperation Council, which includes the UAE, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain and Oman, Emirati rulers have always been suspicious of Saudi intentions.

So when current leader Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan took over after the death of Sheikh Zayed in the mid-2000s, he made a point to free his country from Saudi domination.

Unencumbered by the austerity of Wahhabism and nationalism, he overhauled his country’s military and sought to foster a close strategic relationship with the United States. His approach worked well, earning him the trust of the U.S. as a reliable ally in the Middle East.

The rise of the UAE under MBZ, as he is known, coincided with the decline of Saudi influence in Washington, especially after 9/11.

In fact, as Mohammad bin Salman came to power during Saudi Arabia’s succession crisis, he looked to MBZ for help in lobbying Washington for support. It’s rumored that he doesn’t make a political move without first consulting MBZ.

Yet Saudi and Emirati foreign policies are hardly uniform. The UAE’s is actually pretty bipolar. It is aggressive in the Middle East but subservient vis-a-vis the U.S. and Israel.

Abu Dhabi has clashed with Oman over its relations with Iran, has soured its relations with Kuwait, has launched a ferocious media campaign against Turkey, and has urged MBS to blockade Qatar, which the UAE sees a natural competitor.

In fact, MBZ refuses to accept competitors in the Middle East, North Africa and the Horn of Africa, but he never misses an opportunity to let American officials know how much he values working with them.

Therein lies the problem. MBZ believes he has carved out a niche in the international world order. As he engages with influential leaders of powerful countries, he forgets that the economy of his country depends on global peace and stability.

Abu Dhabi’s principal foreign policy flaw, then, is the climb to regional prominence.

A Useful Proxy

More than anything else, the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990 changed the strategic thinking of Abu Dhabi. That year, it learned that it had to fear the Arab states as much as it fears Iran. Concerns about domination by Saudi Arabia compelled MBZ to modernize the UAE’s armed forces, especially the air force, immediately after his appointment as deputy supreme commander of the armed forces in 2005.

Abu Dhabi, then, has three foreign policy objectives: spread its influence throughout the Middle East, either directly or through alliances; destroy Islamists, whose ideology directly threatens the monarchy, or at least exclude them from public life; and form a permanent alliance with the United States and Israel. These objectives put the UAE directly at odds with Qatar, Turkey and the Muslim Brotherhood.

Following the eruption of the Arab uprisings, Abu Dhabi restructured its national security apparatus, calling for the adoption of an aggressive and preemptive foreign policy employing a combination of soft and hard power.

Abu Dhabi has openly supported counterrevolutionary forces in Egypt, Libya, Yemen and Tunisia and has empathized with the Syrian regime. Despite the UAE alliance with Saudi Arabia in Yemen, its air force killed more than 4,000 soldiers from the government supported by Saudi Arabia. (MBZ also played a significant role in Turkey’s failed military coup in July 2016.)

Its strategy led to expansion in and around the Horn of Africa. The UAE has established military bases in Yemen, one in Eritrea and another in Somaliland, and it operates two air bases in Libya. But interestingly, the UAE depends on U.S., French, British and Italian military bases, in addition to a South Korean contingent, for its protection.

The militarization and interventionism under MBZ’s rule has made the UAE a natural proxy for the U.S. (Former U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis described the UAE as “Little Sparta.”) In this role, Abu Dhabi has served as a U.S. police force in the region, even as it has an embassy in Damascus and enthusiastically endorsed the ill-fated Deal of the Century between Israel and the Palestinian Authority.

But for all of its usefulness, the UAE, somewhat ironically, is no good to the U.S. as a counter to Iran. Despite some past grievances, especially over disputed islands, Iran and the UAE have found ways to work together.

Dubai is vitally important to Iranian commerce, especially at a time of such crippling U.S. sanctions, and there are lots of Iranian private investors in Dubai.

Around 8 percent of the population is of Iranian descent, and about half a million Iranian expatriates live in the country.

Emirati officials may dislike Iran, but geographic proximity and demography compel them to accommodate their larger neighbor.

A Pioneering Country?

MBZ’s foreign policy efforts are beginning to tarnish the image of the UAE and its economy as an oasis of stability and modernity in the restive Middle East. It has also created tension among the UAE’s members, especially Dubai, which would be devastated by any retaliation to such an aggressive posture, reliant as it is on services and foreign investment.

If, say, Iran launched a missile at Dubai, it could bring its economy to a standstill and drive out badly needed Asian laborers. Dubai Port World operates more than 70 seaports worldwide in countries such as Pakistan, France, Canada, Senegal, Australia, Argentina, the United Kingdom, Egypt and Mozambique.

Dubai’s ruler, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, has expressed concern that prolonged military adventurism could eventually hurt business – and indeed already has. Djibouti and Somaliland canceled agreements with Dubai Port World to manage the Doraleh Container Terminal and the Port of Berbera.

All seven rulers of the UAE gathered in an emergency meeting after Iran shot down a U.S. drone and Donald Trump decided to back off from launching retaliatory strikes.

During the meeting, MBR told MBZ that the time had come for the emirates to revisit their foreign policy. He argued that their interventionism costs them too much without gaining anything from meddling in the affairs of other countries.

According to MBR, investing in Libya’s Khalifa Haftar against the internationally recognized government is a vain endeavor, and regime change in Libya and Sudan would neither harm nor benefit the UAE.

Most of the Emirati fatalities in Yemen, which exceed 100 troops, come from the five poor emirates, especially Fujairah. Complaints by their rulers played a crucial role in the decision of MBZ to pull out most of the soldiers from Yemen and redeploy the rest.

The rulers of the poor emirates are dissatisfied with the gross imbalance in the quality of life between Abu Dhabi and Dubai on the one hand and the five northern emirates on the other. For example, per capita income in Abu Dhabi is six times higher than in Ajman. All rulers disagree with the policy of MBZ in the Arab region.

The social contract that ensures a reasonably good quality of life in exchange for unquestioned fealty no longer satisfies the majority of Emiratis who want greater political representation. Abu Dhabi’s advertisement of its Louvre museum as a window on humanity in a new light sits well with the introduction of a Cabinet portfolio for tolerance.

It is thus easy to create the impression that the UAE of the MBZ administration, a third of whose Cabinet is composed of women, is a pioneering Arab country.

The fact that Abu Dhabi operates 18 secret prisons in Yemen, where torture is the order of the day, dims its liberal outlook.

MBZ seems secure in the foreseeable future, but he risks the erosion of his power unless he adapts his regional policies to make them consistent with the aspirations of the people of the UAE.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario