The relationship between inflation and unemployment is real, but far from simple

By Justin Lahart

The Phillips curve hasn’t been behaving like economists expected since the early 2000s. Photo: Kena Betancur/Getty Images

When unemployment goes down, inflation picks up, and when unemployment goes up, inflation cools down. That has been a central tenet of economics for the past 60 years, guiding Federal Reserve policy makers and private forecasters.

But the trade-off between unemployment and inflation, described by economist George Akerlof in his 2001 Nobel Prize Lecture as “probably the single most important macroeconomic relationship,” hasn’t been behaving the way it is supposed to lately.

In 1958 Alban William Housego Phillips, a New Zealand economist whose résumé included stints hunting crocodiles in Australia and operating a secret radio in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp, published the paper that would make him famous. In it, he showed that in the years spanning 1861 to 1957 the unemployment rate and wage inflation in the U.K. were negatively correlated—meaning that when one went up, the other one tended to go down, and vice versa.

That makes sense: When unemployment is low, workers can bargain for bigger wage increases than they can when unemployment is high.

American economists Paul Samuelson andRobert Solowseized on Mr. Phillips’s work, showing in a 1960 paper that it applied to the U.S. as well. They dubbed the downward-sloping line that can be drawn in a chart where the unemployment rate and wage inflation are plotted against each other the “Phillips curve.” (Since wages and prices tend to move together, the Phillips curve holds for price inflation as well.)

But the Phillips curve isn’t a static relationship over the long haul, with any given unemployment rate leading to a predetermined level of inflation. People’s inflation expectations matter, as economists Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps pointed out in the late 1960s and America painfully learned in the 1970s.

The basic insight is that inflation expectations play a role in bargaining over wages. If the unemployment rate is 5% and workers think that prices will rise by 10% annually, they will demand bigger wage increases than they would if they think inflation will be 2%.

Those inflation expectations, meanwhile, are shaped by people’s past inflation experiences. So when inflation started shifting higher in the late 1960s, driven in part by government spending programs that drove the unemployment rate down, inflation expectations eventually shifted higher as well.

The Phillips curve shifted higher as a result, so that any given level of unemployment was associated with much higher inflation than it had been in the past. The Great Inflation had arrived.

It didn’t break until the early 1980s when the Fed, under Chairman Paul Volcker, slammed the brakes on the economy, driving inflation down and resetting inflation expectations lower. Over the next two decades, the central bank, guided by a Phillips-curve framework, kept a tight lid on inflation.

Alban William Housego Phillips. Photo: Alamy

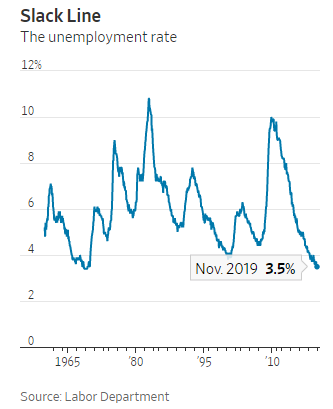

But since the early 2000s, and especially since the financial crisis, the Phillips curve hasn’t been behaving like economists thought it would. When the unemployment rate shot higher following the financial crisis, inflation fell less than Phillips curve models predicted.

And when the unemployment rate fell to 3.5% in late 2019, inflation was remarkably muted. An alternative Phillips curve, based on the pace of gross domestic product rather than the unemployment rate, has run into the same problems.

Some people have suggested that, as a result of forces such as globalization and the reduced bargaining power of workers, the Phillips curve relation is broken.

That probably isn’t true. An economy where wages and inflation don’t have something to do with the supply of labor would be a strange one. Indeed, research conducted economists Peter Hooper, Frederic Mishkin and Amir Sufishows that at the local level in the U.S., the Phillips curve is working quite well, with changes in metropolitan area unemployment negatively correlated with changes in the rate of inflation.

One possibility for why, on a national basis, the Phillips curve has gotten out of kilter may be a downward shift in how low the unemployment rate can go without inflation accelerating. Technology may have made it easier for employers to find employees, for example. And an increased willingness to hire and promote women and minorities may have led businesses to take on workers who in the past were underutilized.

Another possibility is that after years of persistently low inflation, inflation expectations have become so set that changes in the unemployment rate affect inflation less than in the past. That would explain the “flattening” in the Phillips curve many economists believe has occurred, with changes in the unemployment rate associated with smaller changes in the inflation rate than before.

Finally, it could be that after years of inflation coming in below the Fed’s 2% target, inflation expectations have slipped. If that is right, then it could take an even lower unemployment rate than economists think to push inflation meaningfully higher again.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario