Investors are starting 2020 in a sunny mood, but worrying signs from China could spoil the party for industrial shares

By Nathaniel Taplin

The doom and gloom of mid-2019 has been replaced with outright investor optimism.

A big reason: better news from both of the world’s two largest economies.

Before investors go shopping for shares, however, they should take a closer look at China.

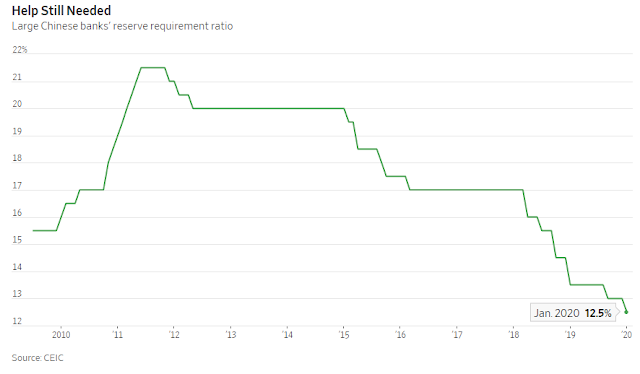

The latest grounds for caution came Wednesday, as China’s central bank cut the amount of cash banks must hold in reserve, releasing an estimated 800 billion yuan ($115 billion) in funds for lending effective Jan. 6. Adjustments to reserve requirement ratios have been the central bank’s favored monetary tool to combat slowing growth since early 2018.

The move was widely expected following calls for additional support for the economy by Premier Li Keqiangin late December. It also partly reflects seasonal funding pressures: Cash demand in China always rises sharply at the end of the Western calendar year and ahead of the Lunar New Year holiday, which falls this year on Jan. 25.

A clerk counts yuan at a bank in Nantong, China. Photo: Xu jingbai/Imaginechina/Associated Press

This year the seasonal liquidity crunch will be even worse than usual due to Beijing’s decision to allow local governments to issue some infrastructure bonds early, absorbing some bond-market capacity, rather than waiting until March when the annual budget is approved. Some important money-market rates, including the seven and 14-day repurchase agreement rates, moved up abruptly in mid-December.

But the reserve ratio cut also represents a tacit admission that things aren’t quite as rosy as some of the recent data seemed to indicate. While there is increasing evidence that China’s export machine is on the mend, other important parts of the economy are looking much weaker than they were six months ago.

China’s housing market is cooling rapidly, and construction activity with it. In December, China’s official construction purchasing managers index logged its weakest reading since early 2016.

The return on assets for indebted state industrial firms, concentrated in housing-dependent sectors such as steel, is also weakening. That makes keeping bond-market liquidity high—and thus state-enterprise refinancing costs low—even more urgent.

The reserve ratio cut will help accomplish this: If the central bank were only concerned with short-term holiday money-market conditions, it could address that through its daily open-market repurchase agreements or other short-term liquidity tools rather than the big blunt instrument of the reserve ratio.

China’s economy enters 2020 with the losers of 2019—private firms and exporters—looking a bit better. Last year’s winners—real estate and state industry—are on shakier ground.

Even as they celebrate the good news, investors should be wary of big rallies in metals, miners and other heavy industrial plays.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario