January’s deadline to use cleaner marine fuel could ripple through the global fuel market on land and sea

By Spencer Jakab

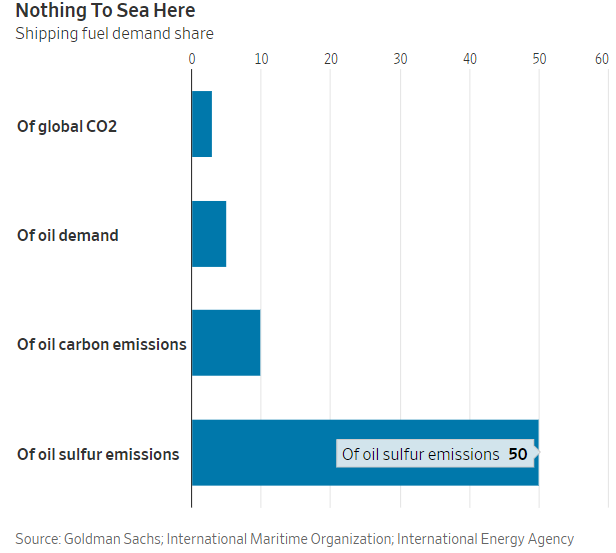

While ships make up just 5% to 7% of global transport oil demand according to Goldman Sachs, they emit about half of sulfur from transport because they use the dirtiest fuel. Photo: ishara s. kodikara/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

Much of the hand-wringing about cleaner fuel has to do with things we encounter daily—trains, planes and automobiles.

But possibly the most significant issue, and certainly the most immediate one, is far out at sea.

That is where most transport by ton miles takes place.

A looming change to rules for maritime fuel in January could cause a splash, making goods and travel of every type more expensive.

The International Maritime Organization is about to reduce the limit on sulfur in fuel oil to 0.5% from 3.5%.

While ships make up just 5% to 7% of global transport oil demand according to Goldman Sachs, they emit about half of sulfur from transport because they use the dirtiest fuel—literally the bottom of the barrel. The move will prevent over half a million premature deaths from pollution globally in the next five years according to a study cited by the IMO.

But saving those lives may not come without significant cost and disruption, according to many in the industry. Refineries, as they are currently configured, can’t simply refine out more sulfur. In addition, there just isn’t enough very-low-sulfur fuel oil to go around.

Tor Svelland,a London-based shipping expert who is actively betting on the dislocations through two investment funds, estimates that about 62,000 vessels world-wide that haven’t installed scrubbers to reduce sulfur will be impacted.

That, in turn, will drive the cost of cleaner alternatives including maritime diesel oil—similar to diesel used by trucks and trains—much higher. Right now there is a $350-per-metric-ton gap between the prices of that and high-sulfur fuel oil in use by most vessels. It could widen to as much as $1,000 next year, reckons Mr. Svelland, adding tens of billions of dollars to shipping costs.

The scramble by refineries could be even costlier—in excess of $200 billion in the case of complete compliance with the rules in the first year, estimates Goldman. This could indirectly impact the price of other products such as gasoline. Switching en masse to cleaner liquefied natural gas, which some cruise ships have done, is impractical and costly for shipping lines in the short term.

The rules have been in the works for years and attempts to delay them have failed. Of course there will be some cheating given the substantial cost advantage available to those skirting the rules, but Wood Mackenzie estimates 85% compliance. Vessels calling on ports in developed countries on either end of their journey risk hefty fines or a loss of insurance coverage.

In theory, the changes already should be reflected in the futures market for various fuel varieties, but the impact has been mild. That may be about to change, says Mr. Svelland, as vessels prepare to embark on journeys that will end when the new rules are in force.

“A lot of people were waiting and waiting. Now it’s showing up in the physical market,” he says.

Aside from people whose health may be improved by less sulfur dioxide, there will be other winners: The moves will be a boon to those refiners best able to provide the middle distillates that will be in greater demand, and it will also boost prices for oil producers pumping “sweet” lower-sulfur varieties such as those in Texas, the North Sea and Nigeria.

“Sour” higher-sulfur varieties, including many from the Middle East, Russia and Canada will in turn be disadvantaged. Power producers that use dirty fuel oil and road builders who may see petroleum dregs turned into cheap asphalt should benefit. So might producers of hydrogen for refiners such as Air Products & Chemicals.

Shipowners who already have made the hefty investment in installing scrubbers—about 10% of global tonnage—might find that what they thought was a decent four-to-six-year payback period turns into more like two years, according to Goldman’s estimates of the disparity between clean and dirty fuel prices.

Companies that can install scrubbers may register a surge in demand once the rules are in place. So might shipyards as older vessels nearing the end of their useful lives are scrapped a bit sooner than they might have been. Another impending and expensive rule change involving ballast-water treatment makes newer ships even more attractive.

Given the very long lead time for the fuel switch and the limited evidence of disruption so far, the IMO switch could be seen as a Y2K-type event with lots of sound, considerable expense but no fury.

Yet it could turn out to be a very big deal.

Mainly people in refining or shipping have warned about the shift. The rest of us may soon feel the ripples.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario