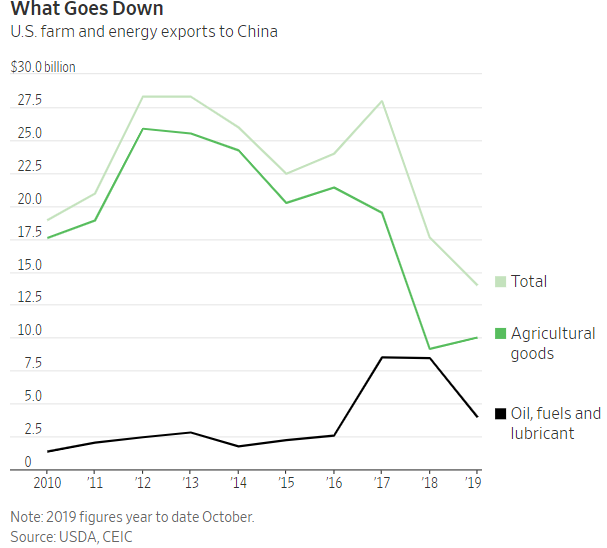

What Goes DownU.S. farm and energy exports to ChinaSource: USDA, CEICNote: 2019 figures year to date October.

By Nathaniel Taplin

After a nervous few weeks, investors may finally get what they want for Christmas. Like many presents these days, it comes from China.

President Trump has agreed to a limited trade deal with Beijing, The Wall Street Journal reports, although neither the president nor Chinese negotiators have yet made an official statement.

The apparent outline runs as follows: China ramps up purchases of farm, energy and other goods to $50 billion in 2020 and likely offers additional concessions on intellectual property protection or financial services. In exchange, the U.S. nixes new tariffs planned for Dec. 15 and halves existing tariffs on $360 billion of Chinese goods.

As investors have seen many times before, deals involving the mercurial Mr. Trump and his inscrutable Chinese peerXi Jinpingcan fall apart at the last minute. Still, markets are already celebrating: China’s Shanghai Composite rose sharply and U.S. stock futures were up 0.4% Friday.

The immediate question-mark overhanging the current deal is the $50 billion figure. China has been dragging its feet for weeks, claiming its own needs don’t justify such large purchases. What has changed?

U.S. agricultural exports to China were just $10 billion in the first 10 months of 2019, down from nearly $20 billion in 2017 before the trade war began. U.S. oil, fuel and lubricant exports were $4 billion over the same period, also about half their 2017 levels. Boosting agricultural and energy exports back to $30 billion or so, therefore, looks achievable, insofar as it would simply put trade flows back where they were.

U.S. agricultural exports to China were just $10 billion in the first 10 months of 2019. Photo: johannes eisele/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

The real question is where the next $20 billion comes from. The overall level of U.S. agricultural exports to the world, while down slightly in 2019 from 2018 levels, has actually been remarkably stable despite the trade war. In 2017, U.S. agricultural exports in the first 10 months of the year were $112 billion. In 2019, after two years of bruising trade conflict with China, they were also $112 billion.

If U.S. farmers somehow massively ramp up production, that risks further pushing down global prices as Brazilian and European goods ditched by China flood back onto global markets. If U.S. farmers don’t raise production that much, China can take back a share of U.S. exports by offering higher prices, but that will make U.S. products less competitive elsewhere, including in the U.S. itself. The U.S. could end up exporting a lot more to China but then sending far less to the rest of the world—or even importing more from Canada and other trading partners as U.S. food prices rise.

Similar questions need to be asked about any “other goods” purchases included in a deal. Does this really represent net new demand for American products, or will it just shift trade flows around again? One possibility: China decides to temporarily stockpile U.S. goods on a gargantuan scale for political reasons, which is perhaps the plan.

Other aspects of the potential deal also deserve investors’ scrutiny. For example, China has already opened its financial-services sector to an extent over the past two years, and has already beefed up intellectual-property enforcement since 2014 with a new system of special IP courts.

Lower tariffs, higher exports and better intellectual-property enforcement are all good things.

But to gauge the real, long-term impact for the U.S. economy, investors will need to read the fine print.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario