By: Hilal Khashan

Mindful of the sectarian divisions that had long plagued Lebanese society, Shihab focused the army’s mission on maintaining law and order without using brute force or antagonizing any religious sects. He did not, for example, heed presidential orders in 1952 and 1958 to quell public protests. He instead saw the LAF as the builder of an authentic Lebanese national identity that integrated all strata of society.

Shihab’s presidential successors, however, have failed to insulate Lebanon from the region’s turmoil, particularly the Arab-Israeli conflict and inter-Arab rivalries. In 1967, Lebanon found itself immersed against its will in the Six-Day War. Since then, several regional actors such as Syria, the Palestine Liberation Army and Saudi Arabia have meddled in Lebanon’s internal affairs – but Iranian involvement, especially since 1982, has proved to be the most consequential.

What distinguishes Iran’s intrusion from all others’ is its creation of a homegrown Lebanese movement, committed to the ideology of the Iranian Revolution, that became the country’s dominant political and military force. Hezbollah came to the fore of Lebanese politics following the end of the civil war in 1989. It was initially seen as an occupation resistance movement but later became a controversial and powerful player in Lebanese politics.

Hezbollah’s Surge

Shiites, who represent one of the three major religious sects in Lebanon (the Maronites and Sunnis are the other two) rose to power in Lebanon following the country’s protracted civil war. In September 1988, outgoing President Amin Gemayel appointed army commander Michel Aoun, a Maronite Christian, as interim prime minister after parliament failed to elect a successor.

Six months later, Aoun declared a “War of Liberation” to remove the Syrian army from Lebanon, but in October 1990, Syrian forces defeated Aoun’s forces and stormed the presidential palace. Aoun sought refuge in the French Embassy and spent 15 years in exile in France. His defeat ended the Maronites’ hold over the LAF, creating a vacuum that was then filled by Shiite and Greek Orthodox officers loyal to Syria and Hezbollah.

Hezbollah managed to bring the Amal Movement, its main Shiite rival, under its wing and used it as a facade to promote its interests in the religiously divided country. Shiite veto power and Syrian backing prevented Sunnis and mainstream Maronites, who mostly boycotted Lebanese politics between 1989 and 2008, from limiting Hezbollah’s control and from blocking its military wing from gaining pseudo-legitimate status.

U.S. Backing for the LAF

The Lebanese army, especially since Gen. Joseph Aoun became commander in 2017, has been critical of Hezbollah’s role in Lebanese defense. The army sees Hezbollah’s claim to protect and defend the country through its own armed faction as an impingement on Lebanese sovereignty and the state’s entitlement to a monopoly on military power. The LAF has received support from many U.S. administrations, from George W. Bush to Donald Trump, which have viewed the LAF as an essential ally and, therefore, a key part of achieving U.S. strategic objectives in the Middle East. One of these objectives is to return Lebanon to its posture prior to the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, which pulled the country unwittingly into regional conflicts.

Over the past 30 years, the LAF leadership’s evolving mission has been to redress the circumstances that led to Hezbollah’s political and military rise. (The 1989 Taif Agreement, which ended Lebanon’s 14-year civil war, called for disarming all militias in the country except Hezbollah’s, citing its role as an anti-Israel resistance movement that was mainly uninvolved in domestic political affairs.)

The United States’ unwavering support for the LAF is aimed at, in addition to combating Sunni militants, discrediting Hezbollah’s claim that it is the only defender of Lebanese territory against foreign threats. In fact, the U.S. believes that the LAF has widespread public support in Lebanon as the only legal and legitimate military in the country.

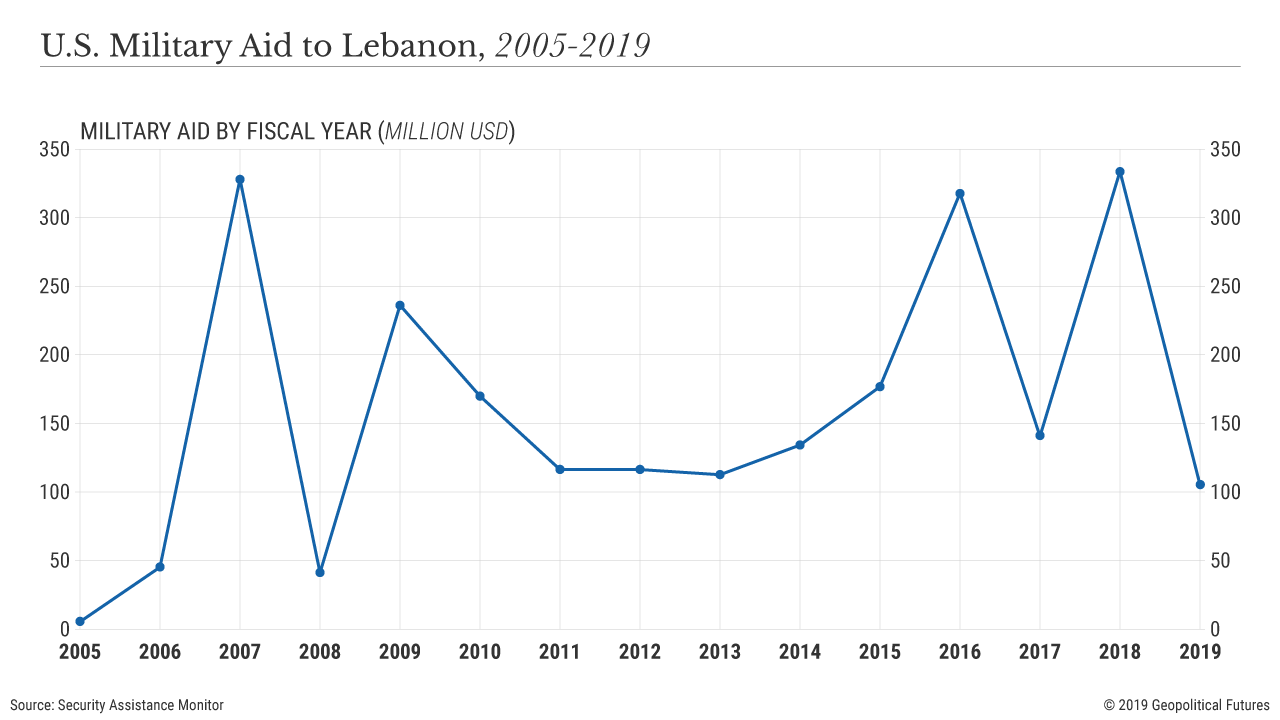

The United States supplies more than 80 percent of the LAF’s weapons and, since 2005, has provided $2.29 billion in military aid. Relations between the Pentagon and the LAF are strong, and senior Lebanese military officers frequently visit Washington to meet with U.S. military and political officials.

The Defense Department’s commitment to supporting the LAF is part of its policy to establish a U.S.-friendly balance of power and refute Hezbollah’s claim that it alone can defend Lebanese territorial integrity. (While Hezbollah insists that the Lebanese army lacks the ability to defend the country against Israel, the group has grossly overstated its own military strength.

It claims to be on par with the Israeli military, but a few thousand fighters, no matter how tenacious they are, would not be able to take on the Israel Defense Forces – especially when you consider that a combination of major Arab armies failed to do so in several wars.)

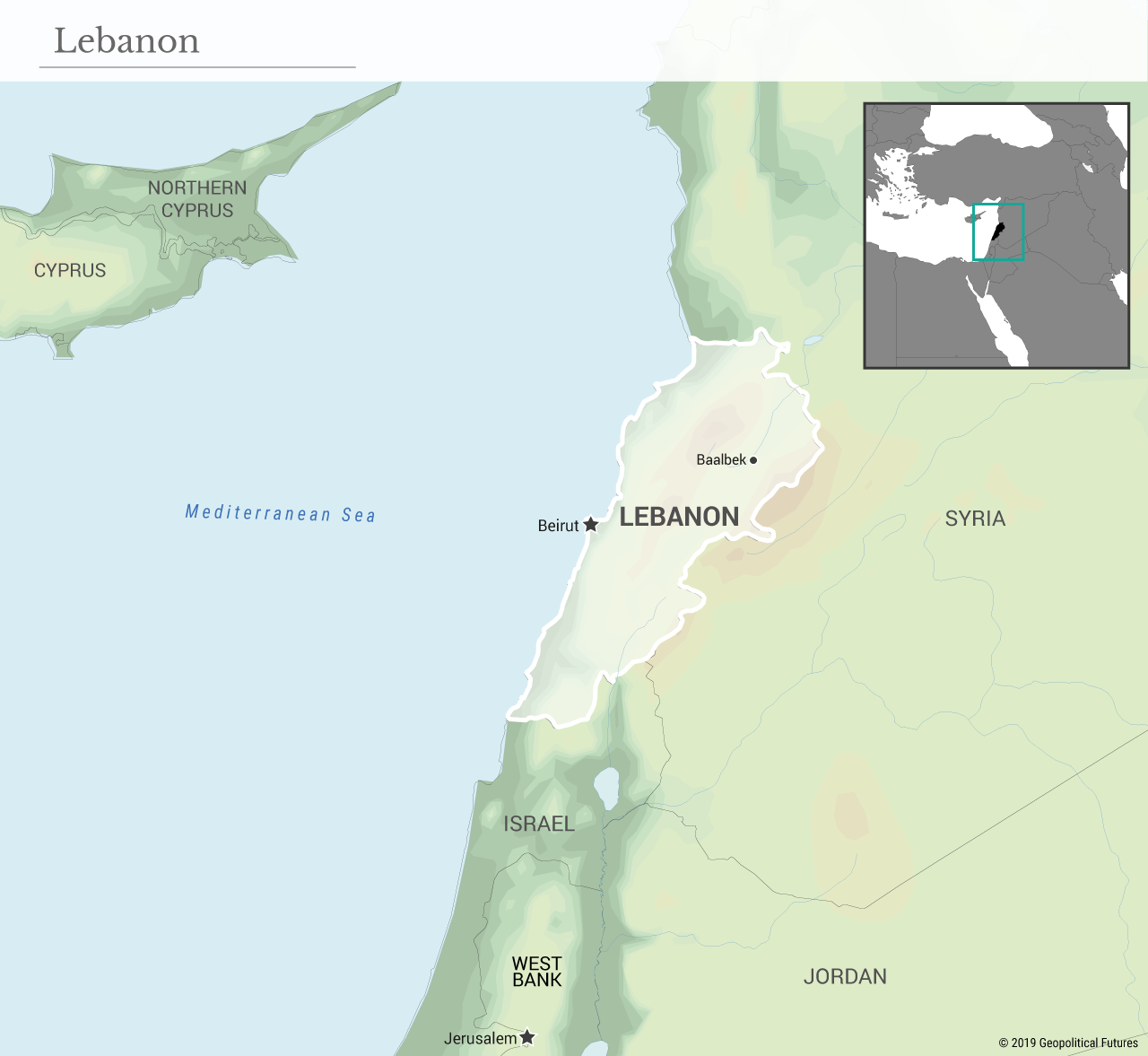

In addition, the growth of the LAF and its focus on counterterrorism training pose a threat to Hezbollah, which views with suspicion the LAF’s acquisition of A-29 Super Tucanos, light attack planes that are particularly effective in guerrilla warfare. In August 2017, the Lebanese army launched Operation Fajr al-Joroud (Dawn of the Barren Ridges) against the Islamic State along the northernmost stretch of the Bekaa Valley.

The precision of the operation stunned Hezbollah. Struggling to maintain its claim to being the superior military force in the country, Hezbollah struck a unilateral deal with IS that allowed IS to withdraw from Lebanon so that Hezbollah could claim credit for the operation’s success.

The Lebanese army command seems determined to assert its authority throughout the country. It has instituted an integrated border management strategy to seal the border with Syria and stop smuggling and human trafficking. U.S. and EU support has been instrumental in the formation of five land border regiments.

The EU funded the establishment of a border management training center in Rayak air base near the Syrian border, and the U.S. continues to supply the LAF with border security equipment, including UAVs, radios, night-vision goggles and heavy machine guns. The border regiments aim at stemming the flow of contraband across the border, which Hezbollah nearly entirely controls. The ultimate objective, however, is to cut off Hezbollah from its Syrian lifeline.

In South Litani, the Lebanese army, along with U.N. peacekeepers, is developing a new military force called “the model brigade” that will eventually take charge of security in the area when the U.N. Interim Force in Lebanon, which has been operating there since 1978, finally leaves the region.

Pressure on Hezbollah Mounts

As protests, soaring inflation and government paralysis continue, cracks in Hezbollah’s Shiite base are beginning to show. Hezbollah’s dwindling financial resources – under strain due to cuts in Iranian funds and decreasing revenue from illicit sources, including money laundering – have severely undermined its ability to provide for Shiites and win their loyalty.

The group has also been under increasing pressure from the United States. In October 2018, the U.S. Justice Department – which has long considered Hezbollah a terrorist group and a bigger threat than Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps thanks to its comprehensive network of sleeper cells spanning five continents – even labeled it a transnational criminal organization.

Hezbollah believes it is facing a massive pro-U.S. coalition – consisting of the Lebanese army command, the central bank, the banking association and the Saad Hariri-led alliance known as the March 14 coalition – aimed at draining the group financially and isolating it politically. If the policy of containment goes well, Hezbollah runs the real risk of losing its ability to financially support Shiites, which would severely impact its ability to recruit partisans and fighters. (As the saying goes, an army marches on its stomach.)

And despite its anti-Israel rhetoric, Hezbollah understands very well the catastrophic consequences for Lebanon in general, and Shiites in particular, of provoking the IDF into an open military confrontation.

Hezbollah will likely resist any changes to the status quo and, as a last resort, may even try to split the army. In recent years, however, the army command restructured the composition of the brigades to prevent any one sect from prevailing. The redistribution of the troops into multireligious units makes vertical defections unlikely.

Only a handful of Sunni soldiers defected during the army’s campaign against al-Nusra and IS. Moreover, the benefits for Shiite officers of joining the LAF far exceed what they might receive from Hezbollah. Shiite defections are also unlikely because the army command has already ruled out initiating a conflict with Hezbollah.

At the recent International Institute for Strategic Studies summit in Bahrain, the Lebanese prime minister’s military consultant said the government had urged the Lebanese army to prepare for a possible showdown with Hezbollah six months before the beginning of the uprising that started in October.

The new balance of power does not aim at strengthening the LAF’s military capabilities to take on Hezbollah; Gen. Joseph Aoun has made it clear to U.S. officials that military action against Hezbollah is extremely unlikely because of the heavy human and political toll it would take. Instead, the army is hoping to build up its own capabilities, which would in turn diminish Hezbollah’s influence in Lebanese politics.

The Army’s Comeback

The key to U.S policy in Lebanon rests on promoting the LAF’s efforts to end Hezbollah’s influence within its ranks. Despite Lebanon’s numerous political and civil upheavals since independence in 1943 and the disintegration of the army on three occasions (in 1976, 1984 and 1990), military units on both sides never opened fire against each other. Military officers have managed to set aside their sectarian affiliations – which created splits in the army during the country’s protracted civil war – because of their strong sense of camaraderie.

The new army command is keen on avoiding the mistakes of the past. If a military showdown does occur in Lebanon, it will have to be started by Hezbollah. And if this happens, it is difficult to imagine that the U.S., which sees the Lebanese army as one of its regional priorities, would not to act, either directly or indirectly through the IDF.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario