By: Jacek Bartosiak

It’s impossible for a state to maintain its status as a major power, even in its own region, without having a military to back it up. In the case of Russia, the transition from Soviet Union to Russian Federation all but gutted its armed forces; the military was simply too closely connected to the state system to withstand the shock of the reforms introduced by Mikhail Gorbachev.

After the Soviet economic system collapsed, the military essentially lost its financing, resulting in lost wages, corruption and an irreparable decline in morale.

It quickly became clear that, despite the chaos, economic collapse and social disorganization, the armed forces still had a job to do: It needed to relocate units and equipment inside Russia proper as well as the now-independent former republic, and it needed to do something with its nuclear arsenal. The latter problem was easy enough to resolve.

Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan signed an agreement whereby all stockpiles would be returned to Russia. The former issue proved much more difficult. “Russian” servicemembers returned to Russia, while servicemembers from the republics stayed there, becoming the foundation of the new militaries of the new states. The result was the dislocation of soldiers who were unprepared for their new environments.

What’s more, Russian soldiers deployed in units based on geography – for example, the contingent of the 14th army of Moldova – remained in place and openly rebelled all the time. Some units even refused to stay. Others, such as those in Georgia and Tajikistan, were drawn into local ethnic conflicts. Still others had newer mandates.

Erstwhile internal military districts, like those in Moscow and the North Caucasus, now found themselves on the frontier of the Russian state, but without the combat experience and mobilization readiness that would normally characterize such districts.

The Russian army of the 1990s was thus weakened at a time when it faced utterly new challenges, including a lack of money, bad demography, a lackluster conscription pool, evasion of service, hazing and other forms of violence among its soldiers.

In the first decade after the collapse of the Soviet Union, funding dried up, and no serious reform reflecting the changed nature of the Russian state and hence its new challenges was made. The once-powerful arms industry barely made ends meet, mainly by selling its products abroad. Troops failed to receive new equipment. The programs of the future were tabled. When fuel and ammunition for routine exercises were delivered, deliveries were often late and short.

Even the salaries of officers, who were widely respected as societal elites, were paid late. Combat readiness practically evaporated, and officers and professional staff often had to work civilian jobs to supplement their income. Military equipment rusted in squares and warehouses, and pilots’ skills atrophied as they logged fewer and fewer hours of flight training.

The results spoke for themselves. Russia, once a powerful country, suffered early defeats at the beginning of the Chechen War (1994-96). Eventually, competently trained and better-equipped units were deployed to Chechnya, but they were still composed of random soldiers from disparate units throughout Russia. It bade poorly for combat readiness, harmonization and overall quality.

Historically in Russia, great military reform was born from a seminal event: a military disaster, a change in the nature of the Russian state or a transformation of the geopolitical environment in which the state operated. Under the czars, the reforms of Field Marshal Dmitry Milyutin were the result of the humiliations during the Crimean War (1853-56). Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin’s reforms were the result of the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05). In the 1920s and 1930s, Mikhail Frunze and Mikhail Tukhachevsky tried to find a way to answer first the threat to the existence of the new communist state and later the military development of Germany which meant to change the world order.

During World War II, Semyon Timoshenko sought to cope with the mighty German war machine; the great reforms of the Red Army were carried out from 1941 to 1945. Gen. Georgy Zhukov executed his reforms in the 1950s as a response to the new security environment in Europe, and in the 1960s with the advent of more sophisticated weaponry – rockets, tactical nuclear weapons and so on. Finally came the great reforms of Field Marshal Nikolai Ogarkov, who overhauled and modernized the army as part of his Revolution in Military Affairs in the 1970s and 1980s.

The post-Soviet debate over military reform, sustained by the failures of the Chechen War, persisted into the Yeltsin era. Policymakers generally agreed on the need for reform but invariably failed to implement it. That changed after Vladimir Putin came to power. With his staunch supporter, Sergei Ivanov, in charge of the Ministry of Defense, minor improvements were made, helped greatly by the rise of oil prices after 2002. Between 2001 and 2007, spending on military modernization doubled, reaching 573 billion rubles (more than $9 billion by today’s exchange rate). Throughout this time, Russian forces became smaller and more agile with improved combat readiness.

Welcome though Putin’s efforts may have been for the military, they were 20 years too late. The armed forces entered the 21st century still armed with Soviet-era equipment and operated in an archaic Soviet-era system unable to rise to the occasion of the new day. The Russo-Georgia War of 2008 demonstrated a terrible state of intelligence and reconnaissance capabilities and a low state of command and communication capabilities. Precision ammunition was particularly lacking, logistics were poor, the basic equipment used by the Russian army was old, and recruits remained poorly or insufficiently trained for modern warfare.

In response to the war, Anatoly Serdyukov, who served as defense minister from 2007 to 2012, introduced modernization measures such as the Armed Forces Development Program that prioritized increasing combat readiness, professionalizing the service and acquiring new weapons.

Military expenses jumped from $57 billion to $91 billion, which he used to address glaring problems: the fact that a unit’s and formation’s constituent parts did not know or train with one another, and that mass mobilization, especially on the country’s periphery, was much slower than it should be. In fact, this was always a problem for the czarist and Soviet militaries, which struggled to mobilize within such an infrastructurally constrained state as Russia. (It’s worth remembering that the Soviets had war plans for mass mobilization, the purpose of which was to be able to wage war with NATO in Europe and with China in the east.

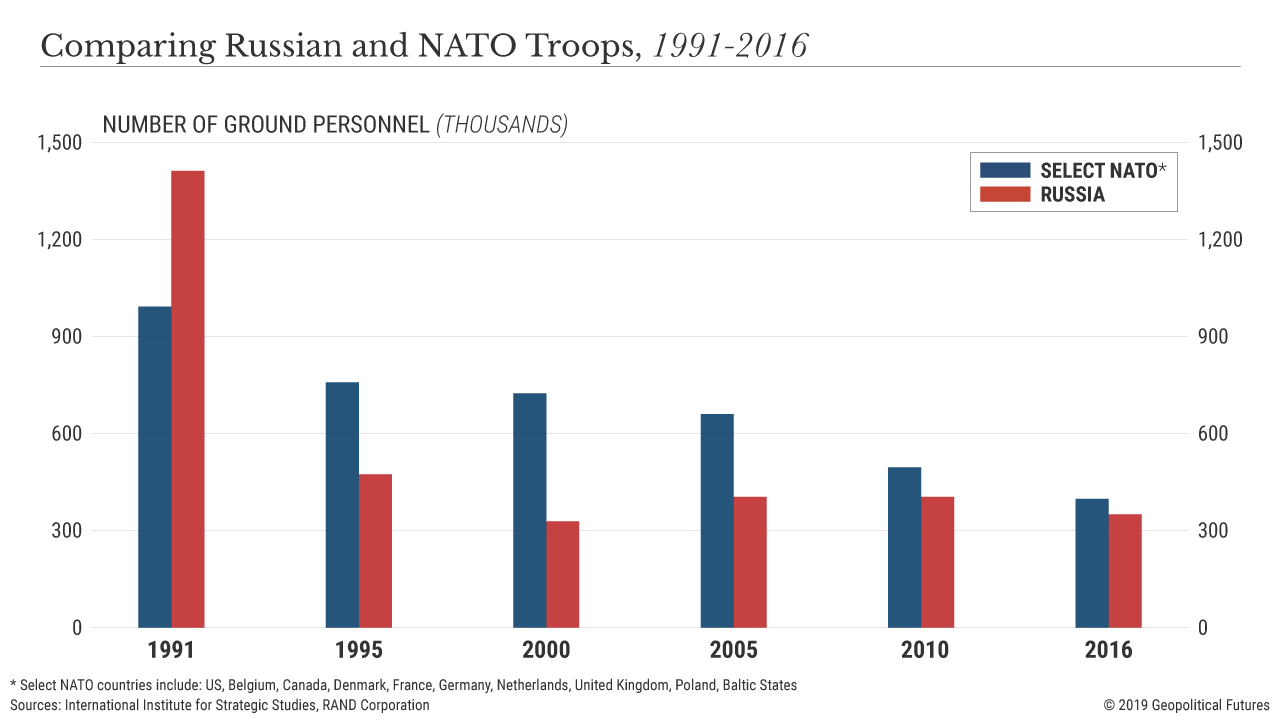

The entire system, however, was focused more on efficiently mobilizing the masses than on their command. There was simply too much administration and too many incompatible equipment systems to put on a line. Russia had so much surplus equipment, in fact, that in 1991, 3.4 million people were serving in the Soviet army, of which as many as 1.2 million serviced army stores.)

Russian military history is replete with attempts at improvement, but it’s safe to say that the beginning of the most significant came with the appointment of Serdyukov. This is a symbolic beginning of the construction of a new Russian army and a real mental revolution in the country. Before his tenure, the command system was simply absurd. It just took a few military humiliations to get there.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario