The European Union Divided Over Belarus

By: Ekaterina Zolotova

European Union member states don’t always share common interests, especially when it comes to foreign policy. Belarus, and its relationship with Russia, is one of the issues on which EU member states don’t see eye to eye.

Germany, for example, has a mostly pragmatic approach to Belarus, whereas Poland is more wary of Minsk’s close relationship with the Kremlin.

These different approaches have pitted Western European countries against Eastern European countries, revealing yet another issue over which the EU is divided.

The question of EU-Belarus relations came to a head last week when representatives from EU member states and Belarus met at the Minsk Forum to discuss Belarus’ place in Europe and the Eastern Partnership initiative, a project to help encourage cooperation between the EU and six former Soviet states: Azerbaijan, Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine.

In past negotiations and diplomatic meetings with Belarus, the European Commission has tried to stay focused on practical issues such as trade and cultural relations; it has not taken steps that could significantly change Belarus’ posture toward Europe or reduce Russian influence in Belarus.

For example, the two parties are drafting an action plan on customs matters for 2020-23. They are also working on an agreement to facilitate more efficient visa procedures for Belarusian citizens traveling to the European Union.

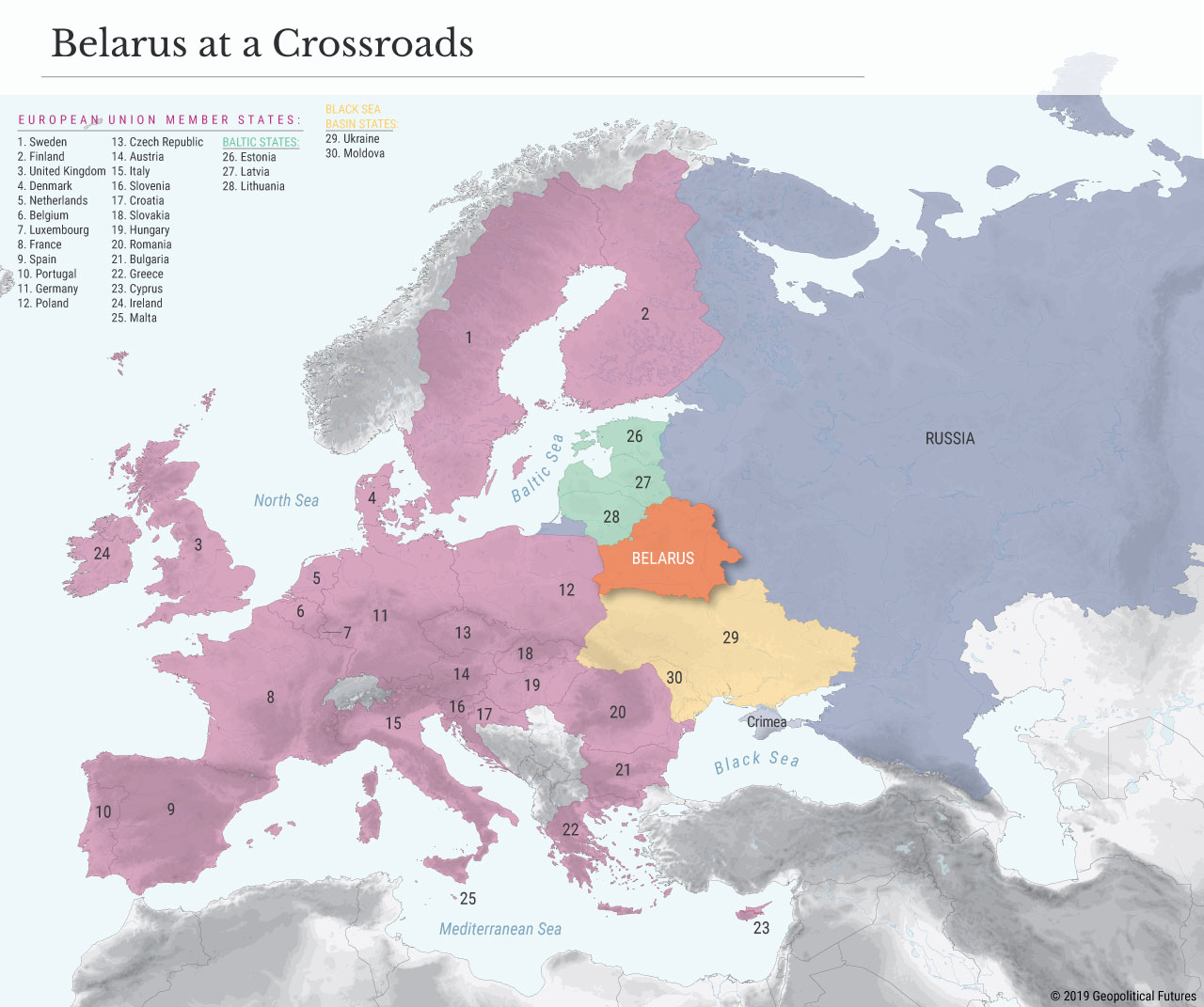

Belarus’ geographic position demonstrates why the relatively small former Soviet nation has drawn such interest from key regional actors. Europeans often speak of the country as a bridge between East and West, sandwiched as it is between Russia and the EU’s easternmost members. For Russia, Belarus has long been one of its closest allies, as it acts as a critical buffer separating the Russians from Western Europe.

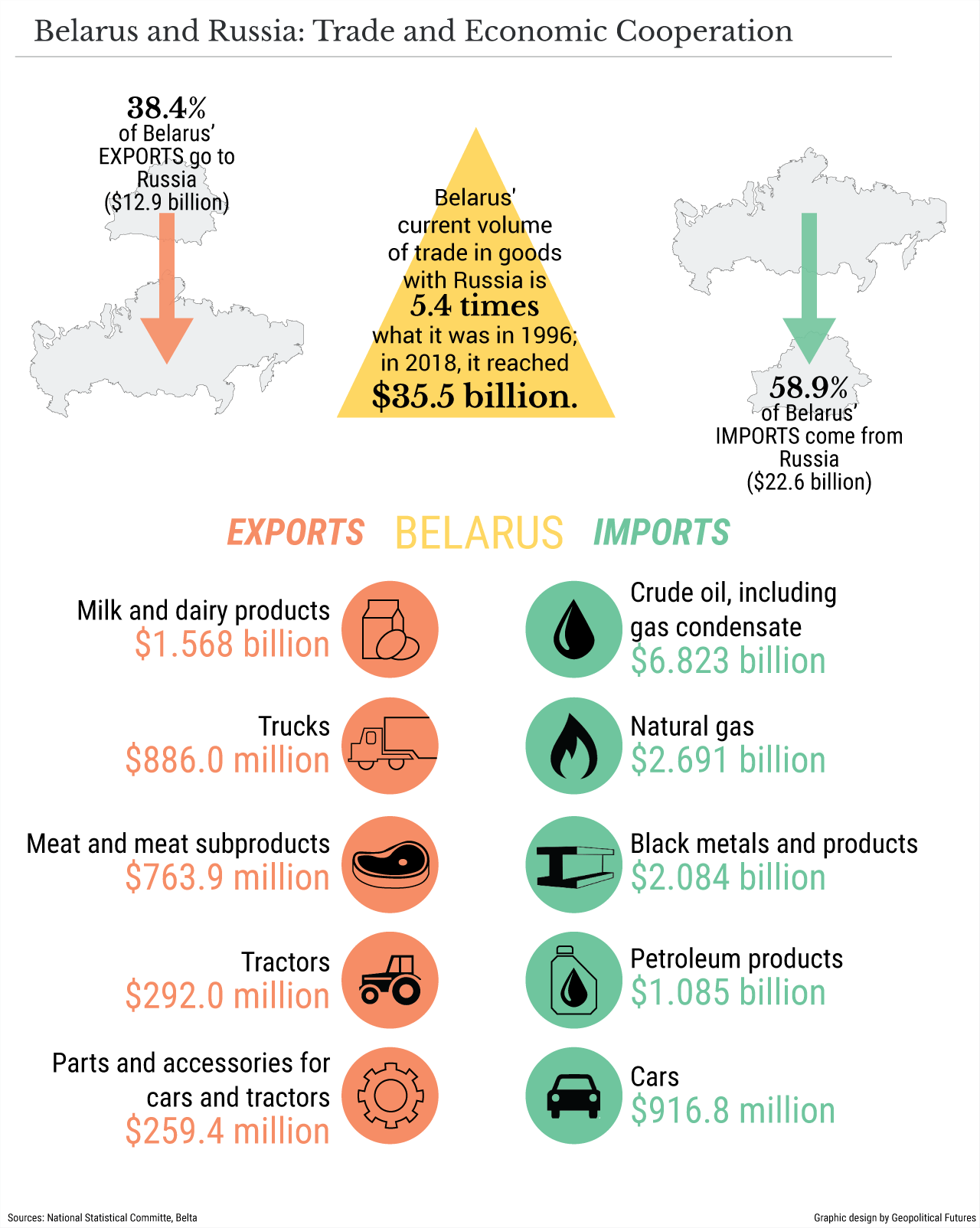

Recently, especially since Russia’s annexation of Crimea, Minsk has taken a more neutral position than it had previously, attempting to balance between Russia and the West. Still, Belarus remains highly dependent on Russia, which is the largest investor in Belarus, accounting for 38.3 percent ($4.2 billion) of foreign direct investment coming into the country in 2018. Russia is also Belarus’ top trade partner, accounting for roughly 50 percent of total trade.

According to data provided by the Union State, an organization devoted to further political, economic and military integration between Belarus and Russia, there are more than 2,000 organizations in Belarus that receive Russian capital and more than 1,300 joint ventures between the two countries. About 60 percent of Belarus’ external public debt is owed to Russia. Belarus is also dependent on Russia for energy – about 90 percent of crude oil imported by Belarus comes from Russia.

One of the areas in which cooperation between the two countries has been the strongest is the military. They share a military doctrine and often participate in joint exercises. Russia also continues to supply Belarus with military equipment; the Kremlin is scheduled to deliver 12 multifunctional Su-30SM fighters to Belarus this year.

If the two countries were to integrate even further, Russia would likely be able to increase its military presence in Eastern Europe, a prospect other countries in the region would see as destabilizing (though this is unlikely to include additional Russian bases in Belarus since Minsk knows this would be a highly controversial move among the Europeans).

Given the level of cooperation between the two countries, as well as continued negotiations over deeper integration within the Union State, very few countries in Western Europe are prepared to try to increase coordination with Minsk. Most don’t have extensive economic ties to Belarus, and even those that do are more interested in maintaining the status quo with Russia than increasing cooperation with Belarus, which might irritate the Kremlin.

That’s because Russia is a significant trade partner and supplier of resources for the EU. Russian energy firm Gazprom, for example, currently supplies 43 percent of the EU’s natural gas needs.

Germany, Europe’s leading economy, is particularly wary of angering Moscow, which provides 33 percent of oil and 35 percent of natural gas consumed in Germany. Trade between the two countries reached $60 billion in 2018. Berlin is therefore unsure of how to approach Belarus. Germany imports large volumes of certain goods, especially machinery, equipment and vehicles, from Belarus and has historically been among Belarus’ top investors.

But cooperation between Berlin and Minsk has mostly been limited to economics, civil society and cultural issues. Germany therefore has not demanded significant political or social changes from Belarus.

Moreover, EU relations with Belarus are still conducted under a 1989 treaty signed between the European Economic Community and the Soviet Union. The treaty is a framework document rather than an association agreement and so does not establish deep levels of interaction. (Belarus is the only state among the six Eastern Partnership countries that does not have a cooperation agreement with the EU.) By engaging with Belarus on this limited level, Germany has managed to avoid threatening Russia’s dominant position in Belarus.

But there is another EU member that is worried about the close relationship between Russia and Belarus: Poland. Reintegration of the Russian and Belarusian states could increase Russia’s influence in Eastern Europe, which Poland sees as a threat. Warsaw, therefore, has supported the Belarusian opposition (though it denies doing so) to try to decrease Russia’s influence in its neighbor. Unlike Germany, Poland – which shares a border with Belarus – does not see Belarus relations as merely a pragmatic issue; it has its own foreign policy objectives separate from those of the EU.

Poland's foreign policy priorities in relation to the former Soviet states include weakening Russia’s geopolitical position by separating Ukraine, Belarus and other countries from Russia; diversifying energy supplies to Poland and Western Europe in order to rely less on Russian supplies; encouraging economic cooperation among Eastern European countries; and expanding its presence in the former Soviet states by investing in them and using cheap labor from Ukraine and Belarus.

Though Warsaw has recently toned down its support of ethnic Poles living in Belarus, it’s very concerned about the possible strengthening of the Russia-Belarus alliance, especially the expansion of military cooperation, which would allow Russia to increase its presence along Poland’s borders.

That’s why Warsaw is trying to reduce Russian influence in the region. Given that Poland is located on the European Plain, it’s a country that’s relatively easy to penetrate by land and has been invaded (and subsequently occupied) multiple times from the east.

Poland is therefore still concerned about the possibility of a Russian military invasion and is looking to increase its own military capabilities and encourage bilateral partnerships, including with the United States. Warsaw has repeatedly asked Washington to increase the number of U.S. troops in Poland and even promised to build a base costing $2 billion. In June, the two countries agreed on the deployment of a squadron of MQ-9 drones and an additional 1,000 U.S. troops to Poland, bringing the total number of U.S. soldiers based in the country to 4,500.

And in November, Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki said the United States said it would increase its troops in Poland by more than 10 times. In addition, large-scale NATO exercises in Europe involving about 37,000 troops from 19 countries (including 20,000 American soldiers) are scheduled for 2020. Poland’s increasing reliance on the U.S. for defense support, at a time when a split is widening between the United States and countries like Germany and France, may turn out to be another source of tension between Western and Eastern Europe.

For Russia, a rapprochement between Minsk and Brussels would be seen as counter to Russian interests. Most EU countries, therefore, are willing to support an independent Belarus only within the framework that Russia has designed. It is more advantageous for them to maintain the current level of cooperation with Minsk than to risk angering the Russians and possibly jeopardizing their own energy security – despite the fact that not all EU member states agree with this approach. Belarus is just one more example of an issue that proves that the EU is far from united.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario