Cracks Appear in the Turkey-Russia Partnership

By: Allison Fedirka

The contradictions in the Turkish-Russian relationship, which seemed on the surface to be blossoming in recent months, are beginning to show themselves. Any one of these signs of trouble on its own may not be important. However, when grouped together, they paint a gloomy picture of what may lie ahead for this bilateral relationship.

As Turkey gains confidence and asserts itself more aggressively, countries will inevitably be forced to react. In the case of Russia, Turkey’s expansionary efforts make it evident that its days of pragmatic collaboration with Russia, particularly when it comes to security and foreign influence, will eventually reach an end. In Syria, Libya and Central Asia, the makings are underway for Turkey and Russia to be competitors more than collaborators.

Syria

Though the civil war in Syria forced Turkey and Russia to work together politically and on military operations, the two ultimately have different endgames. The nearer Syria’s civil war comes to its conclusion, the less compatible the agreed framework will be. Which regional powers gain influence over the different parts of post-war Syria will directly affect their ability to exert influence.

The problem for Russia and Turkey is that they both want the same slice of the pie: northern Syria. Russia’s approach in Syria has been to increase its influence in the region by propping up the Assad government against its enemies, which include Turkey to Syria’s north. Turkey, meanwhile, recognizes that Russia and President Bashar Assad are not going away, but that northern Syria can be a buffer between them and itself.

Russia’s interest in supporting the Assad regime is twofold: to stabilize the region so that the volatility doesn’t spread to Central Asia and the Caucasus, and to maintain a relatively low-cost footprint in Syria (including a naval base at Tartus and a growing number of other military installations) such that it does not fall solidly under the influence of Turkey or Iran.

Moscow does not seek direct control over Syria; it wants to be able to check any expansionary movements or migration of Syrians (especially former fighters and opposition members) to the Caucasus and other Russian territories. Turkey, however, has a more ambitious endgame, which includes direct power projection and territorial expansion into Syria.

Ankara’s current buffer zone in Syria and its efforts to prevent Kurdish settlement in the area feed into Turkey’s long-term strategy to build a more permanent political influence and military presence to counter Russia, Iran and Assad.

Russia and Turkey’s relationships with two closely related militias – the People’s Protection Units (YPG) and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which falls under the YPG’s umbrella – are evidence of their competing interests over the fate of northern Syria. So far, Russia has been modestly successful in containing Turkey by limiting Ankara’s border corridor to the areas around the cities of Ras al Ayn and Tel Abyad (as opposed to the desired area totaling 112 square miles) and halving the number of repatriated refugees to 1 million. With the U.S. pulling out, Russia, in tandem with the Assad regime, has courted YPG/SDF fighters to join Assad’s ranks in support of the regime and against Turkey’s advance.

This puts Turkey in a difficult position. In the event Russia and the Assad regime are successful, the YPG/SDF alignment with Assad’s forces would essentially disband much of Turkey's “peace corridor” and thwart Turkey’s all-out attempt to destroy the YPG and its Turkish affiliate, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Based on a presentation by former U.S. National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien at the Halifax International Security Forum, Turkey’s countermove to Russia’s efforts has been to support the sale of Syrian oil from the SDF-controlled oil fields, thereby enabling the SDF to pay the salaries of its fighters and undercutting Russia’s efforts to convince the SDF to swing over and support Assad.

Eastern Mediterranean

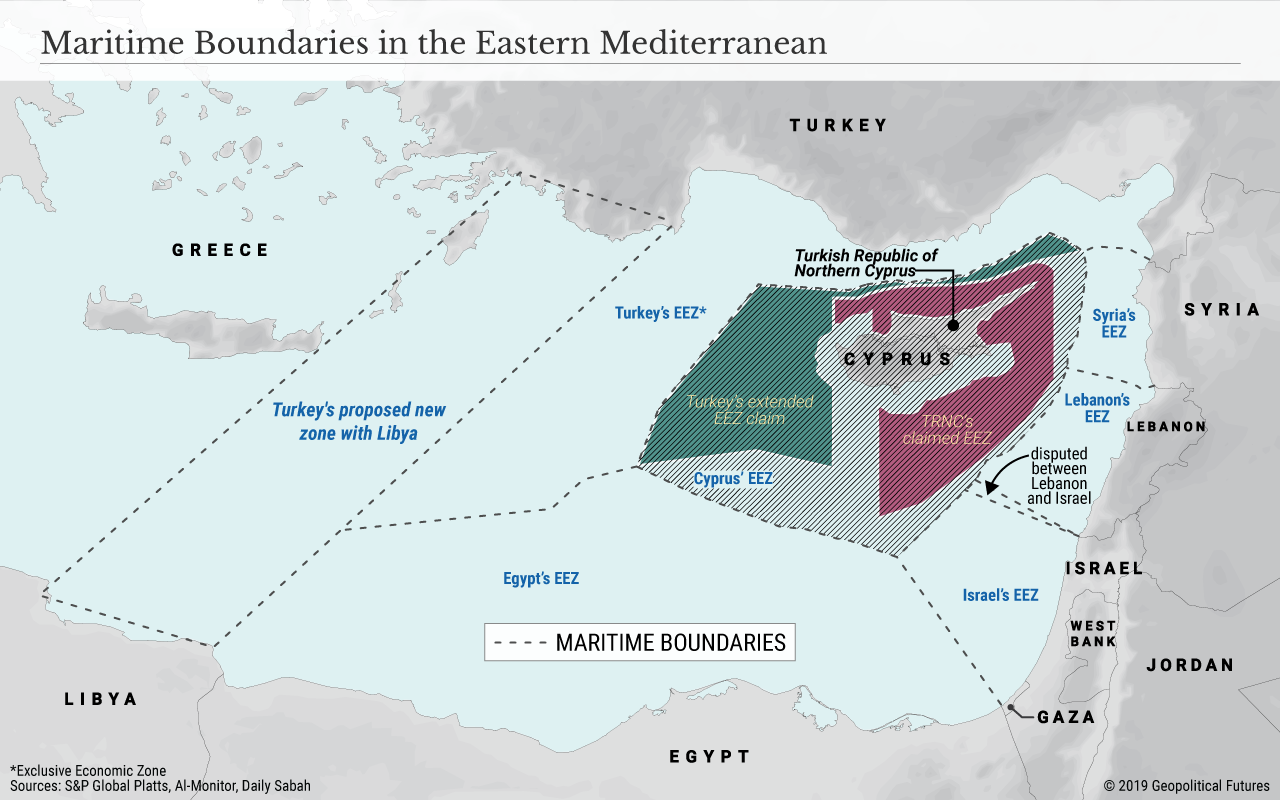

Turkey’s latest forays in the Eastern Mediterranean pose another point of competition with Russia, this time over offshore energy resources. Turkey recently asserted its influence over the Eastern Mediterranean by signing two agreements with the U.N.-backed Libyan Government of National Accord; one calls for military cooperation and the other demarcates maritime zones in which both parties exercise sovereignty. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has even gone so far as to float the possibility of Turkey sending troops to Libya to support the GNA as it battles for control of the country (and the latest agreement with Libya allows for this).

Prior to the start of its civil war, the country was a major producer of oil. Libya’s land and sea holds an estimated 48 billion barrels of oil deposits, the most in Africa and 9th-most in the world. Right now, the GNA has control of oil revenues, while its opponent, the Libyan National Army led by Khalifa Haftar, controls most of the oil fields. The race to take advantage of postwar oil production has already begun, and foreign allies on each side are jostling for position. Russia certainly had as much in mind this year as it sent more soldiers and mercenaries to Libya to back Haftar’s forces.

In a scenario where Libya is stable, European companies will want to increase their presence in Libya's oil industry, since it will be viewed as a reliable source of energy and an alternative to Russian oil. Russia’s presence in the country aims to ensure it gets a piece of the pie on the business end and will still have a hand in energy supplies to Europe even if they don’t directly come from Russia. A strong Russian presence also helps lay the groundwork for greater port access for Russian naval forces that pass through the Mediterranean.

While the idea of Turkish troops in Libya remains suspect – the Turkish military has its hands full in Syria – Turkey and Russia are clearly on opposing sides in Libya. The two countries will likely be able to sort out their differences in the immediate future. Russia does not want to escalate its foreign military ventures, and Turkey faces additional opposition to greater involvement in Libya from well-established rivals such as Egypt and Saudi Arabia, which will make Turkey think twice before acting.

Central Asia

While Syria and the Eastern Mediterranean are currently the two most active areas of growing competition between Russia and Turkey, there is the potential for Central Asia to join the list as well. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Russia managed to keep close economic and military ties with the region. Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan are both members of the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union. Russia ranks among the top four export destinations for Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan and serves as the first or second leading importer for those countries as well as Tajikistan.

In addition, Russia’s prominence in the energy sector has allowed it to join many hydrocarbon production projects and related infrastructure in these countries. In terms of security and defense, Russia serves as the cornerstone for military hardware, training and organization for Central Asia. Russia maintains military bases in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, and Russian troops and equipment have reinforced Tajik forces along the latter’s border with Afghanistan.

Turkey’s footprint in Central Asia pales in comparison to that of Russia and even China, whose increasing economic prowess has eroded Russia’s monopoly on the region. Nevertheless, Ankara’s growing interest and economic initiatives in the region do not go unnoticed and should not be underestimated.

In the past, Turkey has contemplated the grand venture to revive the dream of a pan-Turkic project in which better ties with Central Asia would open to Turkey new opportunities for gas pipelines, military partnerships and even a buffer zone with Russia. Given the initial success in Syria and advancements in the Eastern Mediterranean, the thought of being able to act on such a project in Central Asia is not completely out of the realm of possibility. For now, however, Turkish involvement in the region is primarily economic in nature.

Turkish companies have substantially increased their participation in the region. For example, as recently as 2016, Turkish companies had a negligible presence in Uzbekistan, but now there are more than 750 Turkish enterprises in the country. In Kazakhstan there are now roughly 2,200 Turkish enterprises, compared to 1,616 in 2013.

Bilateral trade has also been on the rise. In January-October 2019, the volume of bilateral trade with Uzbekistan increased by 26.9 percent compared to the same period of 2018, up to $1.97 billion. Trade between Kazakhstan and Turkey from January-August 2019 increased by 63 percent ($782 million) compared to 2018, and totaled $2.01 billion.

Also notable are Turkey’s gains in the Turkmen market, where Russia holds a smaller share than other countries in the region. Based on the limited statistics available, Turkey is Turkmenistan’s lead import partner, accounting for 30 percent of Turkmen imports compared to 10 percent from Russia. (Turkey also outranks Russia in exports).

Security cooperation is fairly nonexistent, though Turkey and Kazakhstan did sign a military agreement that calls for the exchange of officers at national defense universities for study. Right now, Turkey’s influence in Central Asia is still limited, but what’s notable is the speed with which Turkish economic engagement with this region is growing. While Russia likely remains fixated on Chinese encroachment, Turkey is now also creeping into its Central Asian backyard.

Black Sea and S-400s

And of course, no conversation on Russian-Turkish spheres of competition would be complete without addressing the Black Sea and Russia’s sale to Turkey of the S-400 air defense missile system. The Black Sea remains a historic battleground between Russia and Turkey. Turkish control of the Bosporus and Dardanelles, which serve as a gateway for Russian grains and goods to the wider world, makes Russia permanently uneasy of its vulnerability.

Erdogan recently poked the bear over this issue by suggesting that Turkey’s offshore hydrocarbon ambitions may not be limited to the Eastern Mediterranean but could also include the Black Sea. Such rhetoric is mostly political posturing given that both Russian and Turkish hydrocarbon exploration efforts in the Black Sea have not been commercially successful.

While Turkey and Russia are permanently at odds over the Black Sea, the chances for confrontation remain negligible at this point. NATO has a strong interest – and accompanying naval presence – to contain Russia in the Black Sea. Any conflict there would risk drawing in the U.S. and European heavyweights, which is not something Russia wants to deal with.

Turkey, meanwhile, benefits from the status quo.

As for Turkey’s acquisition of the S-400 system from Russia, despite all the hype, the S-400 is far from a linchpin securing long-term Turkish-Russian ties. Since the 1980s, Turkey has made a concerted effort to develop its domestic military industry. This effort has grown in recent years, and it remains a greater priority for Turkey than stronger ties with Russia. However, Russia is more likely to freely share technology than the United States. Turkey’s agreement with Russia on the purchase of S-400s does include a partial transfer of production technologies to the customer.

The U.S., on the other hand, resists technology transfers and often requires other conditional agreements for a major military purchase. Furthermore, Turkey has yet to conduct trial runs on the new system, and it is unclear how effectively it will operate in the Turkish climate (similar Russian systems experienced failures when used in Syria).

There is also the fact that this system, and talks to acquire more from Russia, gives Turkey leverage in talks with the U.S., which is far more valuable to Turkey in the here and now than the S-400 itself. The same is true for the possible sale of Russian S-35 fighter jets in the event the U.S. definitively refuses to sell the F-35 to Turkey.

The signs of an eventual fallout in the Turkey-Russia relationship are already apparent. As Turkey continues to push its influence further abroad, it will naturally start to butt up against other countries that seek to preserve their own interests, especially if they run counter to Turkey’s agenda. For Moscow and Ankara, this means their ability to cooperate will grow increasingly constrained, and both countries will need to pursue their own paths, which will likely clash with the other.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario