Our Nuts Are in Danger

John Mauldin

Life would be so much easier if we didn’t have to worry about our financial futures. Though I suppose we don’t have to worry. Animals don’t. Squirrels instinctively store away nuts and thus live through winter without much thought.

We humans have retirement winters, and we’re more sophisticated than squirrels. We generally outsource the job of managing our nuts/money to professionals. All well and good if we save enough and if the professionals do their jobs right. As we saw last week, the elected squirrels who run Social Security haven’t evolved to face changing conditions. Our Social Security nuts are in danger.

But the problem is even bigger. Today I want to continue this theme using some recent corporate news as our springboard. Economic changes have made future planning increasingly difficult for government retirement systems, private pension plans, and individual investors. How do you generate a reliable income stream for an uncertain but potentially lengthy lifespan in a world where interest rates are barely above zero and possibly below it?

The easy answer is “save more,” but that strategy has limits. We all have current expenses. Yes, we can live simpler lives, but we can’t save 100% of our income. Yet that’s what it will take in some scenarios.

If you’re starting to envy the squirrels, you aren’t the only one.

Big Gaps

Remember “defined benefit” pensions? That is the kind of plan in which the employer guarantees the worker a set monthly benefit for life. They are increasingly scarce except for small closely held corporations.

My US accountant has set up well over 1,000 defined benefit plans, including two for me. His primary customers are dentists. The same rules apply for small closely held businesses as for large corporations. These plans can be great tools for independent professionals and small business owners.

My US accountant has set up well over 1,000 defined benefit plans, including two for me. His primary customers are dentists. The same rules apply for small closely held businesses as for large corporations. These plans can be great tools for independent professionals and small business owners.

But if you have thousands of employees, DB plans are expensive and risky.

The company is legally obligated to pay the benefits at whatever the cost turns out to be, which is hard to predict. The advantage is you can use some hopeful accounting to set aside less cash now and deal with the benefit problems later. The problem is “later” comes faster than you would like, and procrastination can be a bitch.

The company is legally obligated to pay the benefits at whatever the cost turns out to be, which is hard to predict. The advantage is you can use some hopeful accounting to set aside less cash now and deal with the benefit problems later. The problem is “later” comes faster than you would like, and procrastination can be a bitch.

At some point, the risks outweigh the benefits, which is why few large companies have open DB plans these days. But the plans are often still in effect for older workers, and the amounts are large and frequently underfunded. Companies are slowly dealing with the problem.

And that brings us to the lesson for today. On October 7, General Electric (GE) announced several changes to its defined benefit pension plans. Among them:

- Some 20,000 current employees who still have a legacy defined benefit plan will see their benefits frozen as of January 2021. After then, they will accrue no further benefits and make no more contributions. The company will instead offer them matching payments in its 401(k) plan.

- About 100,000 former GE employees who earned benefits but haven’t yet started receiving them will be offered a one-time, lump sum payment instead. This presents employees with a very interesting proposition. Almost exactly like a Nash equilibrium. More below…

The first part of the announcement is growing standard. Employers prefer 401(k) plans because they transfer investment risk to the employees. Other than the matching payments—which end when the worker quits or retires—the company has no future obligations.

The second part is more interesting, and that’s where I want to focus.

Suppose you are one of the ex-GE workers (and I’ll bet I have some readers in that group) who earned benefits. As of now, GE has promised to give you some monthly payment when you retire. Say it’s $1,000 a month. What is the present value of that promised income stream? It depends on your life expectancy, inflation, interest rates and other factors. You can calculate it, though. Say it is $200,000.

Is GE offering to write you a generous check for $200,000? No. We know this because GE’s press release says:

Company funds will not be used to make the lump sum distributions. All distributions will be made from existing pension plan assets in the GE Pension Trust. The company does not expect the plan's funded status to decrease as a result of this offer. At year-end 2018, the plan's funded ratio was 80 percent (GAAP).

So GE is not offering to give away its own money, or to take it from other workers. It is simply offering ex-employees their own benefits earlier than planned. But under what assumptions? And how much? The press release didn’t say.

If that’s you, should you take the offer? It’s not an easy call. First, you are making a bet on the viability of General Electric. In September 2000, GE stock traded at $58+ per share. As I write this it is $8.45. The board has slashed dividends and the dividend yield is now only 0.47%.

As of April, GE had $92 billion in liabilities in its pension plan, on assets a little below $70 billion. Commendably, the company is “pre-funding” $4–5 billion into the DB plan. As we will see, however, this is chump change to the actual obligations.

In various ways, the choice GE pensioners face is one many of us will have to make in the coming years. GE isn’t the only company in this position.

You’re still affected even if you don’t have a DB plan. Lots of people are reaching retirement age to find they only have 80% (and often less) of their “fully funded” amount. They have to fill the gap somehow. Most often, that means reducing expenses or working longer, if you’re able.

You’re still affected even if you don’t have a DB plan. Lots of people are reaching retirement age to find they only have 80% (and often less) of their “fully funded” amount. They have to fill the gap somehow. Most often, that means reducing expenses or working longer, if you’re able.

Rising Pressure

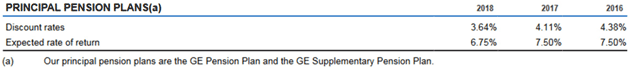

When GE says its plan is 80% funded under GAAP, it necessarily makes an assumption about the plan’s future investment returns. Here’s what they say in the 2018 annual report.

Source: GE

I dug around and found the “expected rate of return” was 8.50% as recently as 2009, when they dropped it to 8.00%, then 7.50% in 2014, to now 6.75%.

So over a decade they went from staggeringly unrealistic down to seriously unrealistic. They still assume that every dollar in their pension fund will grow to almost $4 in 20 years.

So over a decade they went from staggeringly unrealistic down to seriously unrealistic. They still assume that every dollar in their pension fund will grow to almost $4 in 20 years.

That means GE’s offered amounts will probably be too low, because they’ll base their offers on that expected return. GE hires lots of engineers and other number-oriented people who will see this. Nevertheless, I doubt GE will offer more because doing so would compromise their entire corporate viability, as we’ll see in a minute.

In any case, more companies will do such things and affected workers won’t be happy. We’ll see the same in state and local government pensions, which are often even more underfunded and have even more absurd investment projections. These are becoming untenable and lump sum offers like GE’s help highlight that fact.

This, in turn, will raise pressure on plan sponsors to reduce those projections, which will increase the amounts they must contribute to their plans, which (for the corporate ones) will reduce earnings.

See where this is going?

We are right now entering an earnings season that may not be disastrous but doesn’t look too impressive, either. It is getting harder to justify the valuations investors place on many stocks.

If you take out the buyback activity from companies themselves, and the index funds and ETFs that buy indiscriminately as yield-starved investors give them more cash, who is really buying stocks in any major way?

And what happens when they stop buying?

If you’re holding stocks, you better have an answer.

And what happens when they stop buying?

If you’re holding stocks, you better have an answer.

Victoriously Breaking Even

In last week’s Social Security discussion, I noted a fatal flaw in ideas to convert the system into private accounts. Two flaws, actually: 1) Most people don’t know how to invest successfully and 2) now is a terrible time to learn.

(Note, that probably doesn’t include you. You’re reading this letter so you have at least some basic economic and financial literacy. But you represent maybe 5% of the population.)

I dislike saying “it’s different this time” but it really is. Today’s conventional investment wisdom came from an era when there was this thing called “risk-free rate of return.” Everyone could count on earning something, though perhaps not much, without risking it all. Inflation might erode your principal over time but you could at least see it coming.

Now there is no such option. Banks and Treasury securities pay zero, almost zero, or slightly below zero in some places. Don’t like it? Start adding risk. That is your only choice now.

We are in a world where simply breaking even counts as a victory… and that is a serious problem if you need to fund a long retirement.

My friend John Hussman’s September letter, Going Nowhere in an Interesting Way, is a fascinating and important read on this topic. (Over My Shoulder members can read my annotated version here.)

Hussman’s main point: It’s folly to assume stocks will continue performing the way they have in recent years. First, the last two decades haven’t been so great. The S&P 500 total return since 2000 was just 5.4% annually and getting there took the most extreme valuations in US history.

He calculates that assuming 4% nominal growth in economic fundamentals and a historically normal valuation 20 years from now, average annual gain for the next two decades will be -1.0%. Yes, that’s a negative sign.

He calculates that assuming 4% nominal growth in economic fundamentals and a historically normal valuation 20 years from now, average annual gain for the next two decades will be -1.0%. Yes, that’s a negative sign.

Ok, that’s just stocks, you may say. I’m a bond guy. Fair enough. So maybe instead of -1.0% you’ll earn a positive 2%. That still makes real growth difficult.

Investment math is actually pretty simple if your return assumption is 0%. Calculate how much you need to retire, and save that much. Hussman does it more elegantly.

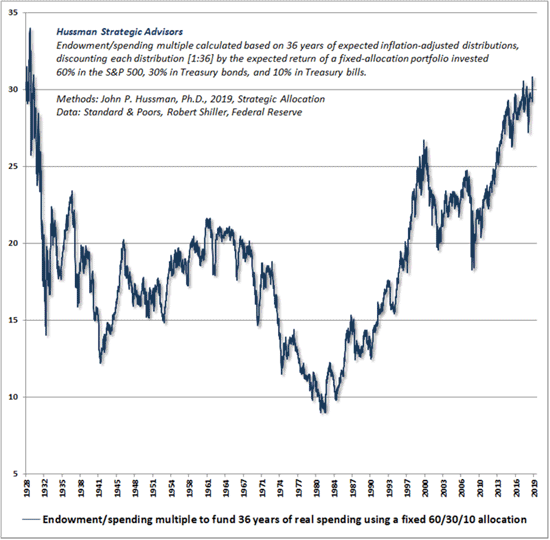

Suppose an investor has accumulated a lump-sum of savings, and wants to finance a long-term stream of real, inflation-adjusted spending. How large must the initial “endowment” be, as a multiple of annual spending, to finance those future outlays, assuming that it’s passively invested in a conventional portfolio mix (60% S&P 500, 30% Treasury bonds, 10% Treasury bills)?

As a convention, we assume a 36-year horizon, representing a 64-year-old investor hoping to fund spending over a potential 100-year lifespan. There’s nothing special about that horizon, and we obtain similar results using any horizon beyond about two decades, because long-dated distributions have very little impact on the total present value.

The chart below presents our estimate of the Endowment to Spending Multiple going back to 1928. The equity market return estimates are based on the Margin-Adjusted P/E before 1950, and the ratio of nonfinancial market capitalization to corporate gross value-added after 1950. The bond market return estimates use the yield to maturity on long-term Treasury bonds at varying horizons.

You’ll notice that the current E/S Multiple is over 31, which basically says that if you insist on passively investing a lump-sum in a conventional portfolio mix in order to fund your retirement, you’d better already have nearly all the dollars you hope to spend, because the prospects for significant long-term capital growth from present valuations are dismal. Contrast this with 2009, when the estimated E/S multiple was 18, or with 1982, when the E/S multiple fell to a record low of 9.

A pretty dismal outlook: If you want to fund an income stream, your lump sum should be 31X the annual income you seek.

But Wait, There’s More

At the risk of sounding like Ron Popeil of Ronco fame (But Wait, There’s More!), whom readers of a certain age will remember nostalgically, there is more. Sadly, you can’t buy it on late-night television.

The reality is simple. Valuations are high and returns based on historical numbers do not suggest anything close to the 6.75% GE expects, let alone the ridiculous numbers public pension plans expect.

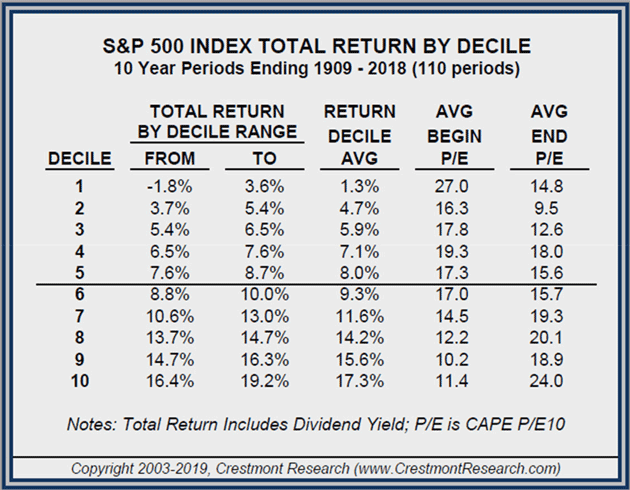

I asked mi buen amigo (I’m trying to learn Spanish) Ed Easterling of Crestmont Research to send me his latest numbers. Based on historical numbers using the Shiller model (other models would be slightly worse) it looks like this. We are currently in the top decile.

Get that? Historical returns based on 110-year models suggest future returns will be anywhere from -1.8% to +3.6%, from where we are today.

Note that 3.6% compound is the top end past historical performance. Also note that I have continually cited academic arguments that the debt situation that we are in today, both as a government and privately, preclude the potential for above-historical-average growth, suggesting lower growth is more likely.

Note that 3.6% compound is the top end past historical performance. Also note that I have continually cited academic arguments that the debt situation that we are in today, both as a government and privately, preclude the potential for above-historical-average growth, suggesting lower growth is more likely.

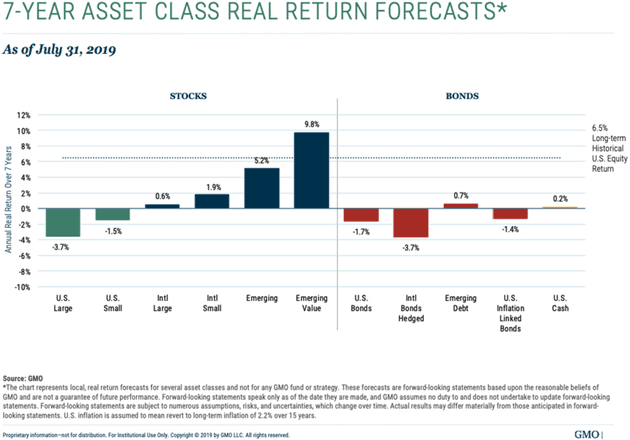

Then quickly, let’s look at the seven-year projected returns from GMO:

Note that these are real returns and not nominal returns. So GMO is actually projecting seven-year returns somewhere around -1.5%. Still quite ugly.

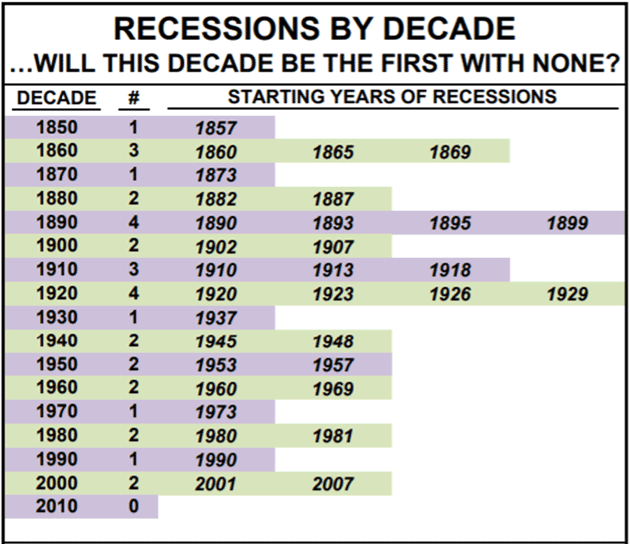

What happens when we have a recession? Remember those ugly things? Pension plan assets suffer a major hit and unfunded liabilities soar! Do you really think central banks can forestall recessions forever? When they are already at the zero bound? Look at the historical frequency, again from Crestmont Research.

Source: Crestmont Research

We are in the first decade to have no recession in, well, forever. Think we can dodge that bullet in the 2020s? Gods forbid, what happens if we have two? The stock market goes sideways for a really long time. Kind of like the 2000s. Then what does GE’s 6.75% return assumption look like? Especially in the zero-bound world of bonds? The answer is “burnt toast.”

Let’s generously assume a 2%+ dividend yield from where we are today. But the chance of a multiple expansion is damn near zero. The Shiller multiple is already 28.6%. (Yes, I get that you can spin P/E multiples numerous ways, but Nobel Laureate Bob Shiller does as well as anybody to reduce the spin.)

GE has $92 billion in pension liabilities offset by roughly $70 billion in assets, plus the roughly $5 billion they’re going to “pre-fund.” But that is based on 6.75% annual return. Which roughly assumes that in 20 years one dollar will almost quadruple. What if you assume a 3.5% return? Then you are roughly looking at $2, which would mean the pension plan is underfunded by over $100 billion—and that’s being generous. GE’s current market cap is less than $75 billion, meaning that technically the pension plan owns General Electric.

This is why GE and other corporations, not to mention state and local pension plans, can’t adopt realistic return assumptions. They would have to start considering bankruptcy.

If GE were to assume 3.5% to 4% future returns, which might still be aggressive in a zero-interest-rate world, they would have to immediately book pension debt that might be larger than their market cap.

GE chair and CEO Larry Culp only took over in October 2018. We have mutual friends who have nothing but extraordinarily good things to say about him. He is clearly trying to both do the right thing for employees and clean up the balance sheet. He was dealt a very ugly hand before he even got in the game.

GE needs an additional $5 billion per year minimum just to stave off the pension demon. That won’t make shareholders happy, but Culp is now in the business of survival, not happiness.

That is why GE wants to buy out its defined benefit plan beneficiaries. Right now, the company is on the wrong side of math. It doesn’t have anything like Hussman’s 31X the benefits it is obligated to pay. Nor do many other plans, both public and private. Nor does Social Security.

To be clear, I think GE will survive. Its businesses generate good revenue and it owns valuable assets. The company can muddle through by gradually bringing down the expected returns and buying out as many DB beneficiaries as possible. But it won’t be fun.

Pension promises are really debt by another name. The numbers are staggering even when you understate them. We never see honest accounting on this because it would make too many heads melt.

And again, a recession is probably coming in the next year or two. The Treasury yield curve has been inverted for three months now and Campbell Harvey, who pioneered that indicator, says it is “flashing code red.” This will further aggravate the pension problem.

If I am a GE employee who is offered a buyout? I might seriously consider taking it because I could then define my own risk and, with my smaller amount, take advantage of investments unavailable to a $75 billion plan.

We are like a football team facing a very tough schedule. Winning will take a solid team working together. Going it alone will be difficult in the 2020s.

Announcing “7 Deadly Economic Sins” Week

Regular readers know my “Things to Worry About” list is pretty long: unsustainable national debt, the fact that nearly 50% of all corporate bonds are teetering on the edge of the BBB cliff, power struggles between competing nations, the insanity of Modern Monetary Theory, a growing partisan split in the US and Europe, an exceedingly hostile US-China relationship, and the threat of negative interest rates.

I think all of these warrant taking a closer look, so October 14–20 will be “7 Deadly Economic Sins” Week at Mauldin Economics.

Seven of my closest friends and I will sit down for thoughtful conversations with our own Jonathan Roth. You probably already know them: Louis Gave, Grant Williams, Peter Boockvar, Lacy Hunt, George Friedman, William White, and Samuel Rines.

They’ll all give you their take on the root causes of the coming global economic crisis.

On Monday, we will start the week with me talking about the deadly economic sin of Lust. Please watch for my emails throughout the week so you won’t miss this special treat.

New York and Butterflies

Other than being in New York October 21 and thereabouts, I’m trying to stay close to home. And when I say home, I can now say that I have finally closed on my home here in Dorado Beach East, Puerto Rico. Getting a loan here is kind of like a Spanish soap opera unless you are willing to pay the going rates. I am paying close to 6%, a far cry from the 2.375% mortgage I had in Dallas. Seriously, there is an opportunity for a jumbo mortgage lender in Puerto Rico. Under 5%, you can sweep the market. Refi’s will line up. On solid loans.

The eye doctor says I am okay and so back to the gym tomorrow. Patrick Cox and Terry Coxon are coming this weekend to discuss funds focused on biotechnology investments. It will be a fascinating weekend of speculation.

And finally, one picture from the butterfly sanctuary my wife Shane has literally created in our home. Seriously, she is raising butterflies, mostly Monarch but also a few other species. It is fascinating to watch them go from eggs to caterpillars to cocoons to butterflies. Here is one of her babies…

And with that glorious image I will hit the send button. You have a great week while we all contemplate a lower-return future. And figure out how we beat the average.

Your creating a team to control our future analyst,

John Mauldin

Co-Founder, Mauldin Economics |

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario