Strange Times

by: The Heisenberg

Summary

- In the week ahead, Jerome Powell faces a trial by fire on Capitol Hill.

- His plight underscores the difficulty in conducting monetary policy in an environment where the tail often wags the dog and political pressure is unrelenting.

- Meanwhile, PIMCO says it's time investors get used to central banks that are no longer independent.

- One way or another, policy normalization appears to be an impossibility.

- Get ready for more mind-bending market distortions.

- His plight underscores the difficulty in conducting monetary policy in an environment where the tail often wags the dog and political pressure is unrelenting.

- Meanwhile, PIMCO says it's time investors get used to central banks that are no longer independent.

- One way or another, policy normalization appears to be an impossibility.

- Get ready for more mind-bending market distortions.

Market participants have spent months obsessing over the following simple chart, which has served as fodder for countless "something has to give" articles in 2019.

The supposed "disconnect" between plunging bond yields and record-high stocks is hardly a mystery and, as documented previously, it's not necessarily true that it has to "resolve" itself by stocks diving or yields exploding higher.

In the simplest possible terms, the concern is that the bond market is "saying" something dire about the outlook for growth and stocks are simply ignoring that warning.

The myriad curve inversions we've seen over the past several months lend credence to "looming recession" narrative which, again, stocks aren't heeding.

But in reality, what you see in that chart is easy enough to explain. 2019 has been the year of the coordinated dovish pivot from central banks including, of course, the Fed. That pivot is predicated on the same growth jitters reflected in developed market bond yields. Stocks are simply "saying" that rate cuts, dovish forward guidance and other measures will likely mean a recession is averted.

Because a renewed commitment to accommodative monetary policy means abundant liquidity, an end to quantitative tightening in the US, a possible return to monthly asset purchases in the EU, the postponing of any push towards normalization in Japan and rate cuts across multiple locales, bonds, stocks and credit are all bid, and so is gold on the assumption that easing amounts to currency debasement.

You could also argue that bond yields are reflecting lower estimates of the neutral rate and lower inflation expectations, neither of which need necessarily presage the kind of disaster which should prompt stocks to sell off.

While all of this is easy enough to explain in the context of the post-crisis monetary policy regime, it leads to strange outcomes - perverse dynamics, as I'm fond of calling them. The most ubiquitous of these is the famous "bad news is good news" paradigm, wherein poor economic data is welcomed as long as it's not overtly dour, because lackluster data underscores the need for rate cuts and central bank accommodation. The flipside of that is simply that good news can be bad news if something like, to use Friday's example, a blockbuster jobs report hits at a time when the Fed is on the fence regarding a rate cut at an upcoming meeting.

We're all used to this particular strange state of affairs by now, but what's new is that it's colliding with President Trump's penchant for boasting about the US economy. We hit while I called "peak cognitive dissonance" on Friday when, literally minutes after the jobs report hit the tape, Larry Kudlow and Peter Navarro were dispatched to TV news networks to sing the praises of the economy while simultaneously insisting that rate cuts are not only desirable, but necessary. Later, in remarks to reporters, Trump similarly oscillated between boasting about "great numbers" and employing his "rocket ship" metaphor to explain why the Fed should cut rates. This continued nearly until midnight.

At 11:24 PM on Friday evening, Trump said this on Twitter:

Strong jobs report, low inflation, and other countries around the world doing anything possible to take advantage of the United States, knowing that our Federal Reserve doesn’t have a clue! Our most difficult problem is not our competitors, it is the Federal Reserve!

I call this "peak cognitive dissonance" because while we've all become accustomed to finicky traders and "spoiled" markets reacting badly to this or that data point on the assumption a brighter economic outlook might compel central banks to tweak their forward guidance, we're now witnessing the President of the United States all but demanding rate cuts (and a return to QE, by the way) when the economy just created 224k jobs.

The only way that makes sense (and I say this objectively, not derisively) is in the context of countries where both fiscal and monetary policy are explicitly or implicitly beholden to the executive. Countries like, for instance, Turkey, where President Erdogan fired the central bank governor on Saturday for not cutting rates.

As I've been over on countless occasions (both on my site and on this platform), when the market starts leaning hard into rate cut bets, it is dangerous for central banks to disappoint those expectations. That is most assuredly an example of the tail wagging the dog, but that doesn't necessarily mean the dog is happy about the situation. That is, contrary to what you might be inclined to believe if you spent your time perusing conspiratorial blogs, the main argument for not disappointing lopsided market expectations if you're a central banker is not that you want to inflate stock market bubbles.

Rather, the argument for not blindsiding markets is that doing so risks triggering a messy unwind of crowded bets, a scenario which, depending on the setup, could tighten financial conditions (e.g., via a reversal of the "wealth effect" as stocks fall or through wider credit spreads). When financial conditions tighten significantly, it makes the case for easier monetary policy, which means disappointing initial market expectations could end up creating a scenario where what would have been preemptive easing turns into a reactive cut later. That isn't desirable, as it suggests policymakers were behind the curve.

Normally, in a situation like we're facing now as the Fed heads into the July meeting, Jerome Powell and his colleagues could simply stick to a moderately dovish line for the next couple of weeks, coast into the pre-FOMC blackout, then deliver a 25bp rate cut accompanied by a promise to do more if necessary. There are all kinds of ways to justify that, even after the June payrolls report.

Unfortunately, it isn't that simple. Because thanks to incessant public demands from the Trump administration, any rate cut that isn't clearly necessary will be seen as a political move.

While markets won't care one way or another what prompted the cut in the near-term, over the longer-term a Fed that's seen as overtly political will lose its credibility. Meanwhile, some Democrats will doubtlessly insist that the Fed has lost its independence and they won't have to look very hard to find evidence to support the allegation (hint: they'll just roll out clips of the President talking to reports and cite his dozens upon dozens of Fed tweets).

That's the setup for Powell's semi-annual monetary policy report to Congress which he'll deliver on Wednesday and Thursday. For all the reasons noted above, this normally mundane affair has the potential to become a spectacle, especially if the President live-tweets it (which is entirely possible).

If the Fed doesn't intend to cut at the July meeting, Powell (and the half-dozen other officials who will speak this week) will need to start walking back market pricing now, to ensure positions are squared and expectations recalibrated by the end of the month. You can read a full account of how expectations evolved on Friday in the "cognitive dissonance" post linked above, but suffice to say markets are still priced for a 25bp cut.

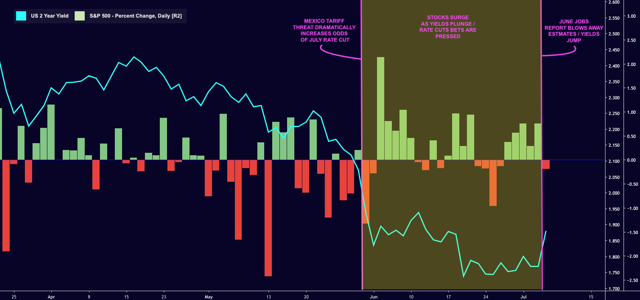

I continue to think staying on hold (i.e., not cutting) at the July meeting is a wholly untenable proposition. If the Fed manages to walk back expectations and STIR traders price out the July cut, stocks will likely roll over. That doesn't have to entail a dramatic selloff, but what it does mean is that equities probably can't sustain record highs if the rates market completely takes a July cut off the board. I've used the following chart before, and I'll update it and use it again here (with some new annotations and colors):

That isn't the most precise way to illustrate the point, but it is the most straightforward. 2-year yields plunged as a July cut became (nearly) everyone's base case after the Mexico tariff threat, and the S&P surged. On Friday, 2-year yields jumped the most since January 4 as the jobs report effectively took a 50bp July cut off the table. Stocks didn't like that. They'll like it even less if the market starts to price out even a 25bp cut.

That is the reality Powell finds himself confronted with as he trudges wearily up to Capitol Hill, where he will most assuredly be asked if the Fed is feeling pressure from the White House to cut rates.

The Fed chair could plausibly use his testimony to reassert Fed independence and to recalibrate market expectations for the July meeting by talking up progress on trade (i.e., the G20 deal between Trump and Xi Jinping), the jobs report, somewhat better inflation data and reduced uncertainty. But you can be absolutely sure that market expectations and the consequences of disappointing them will not be far from his mind. It's also probably occurred to Powell that if he says anything this week to make markets reassess whether a July cut is in the cards and his remarks trigger a selloff in equities, the whole thing (his comments and their connection to any stock slide) will likely be amplified by comments from the President and his advisors.

So, what if Powell wants to make the case for a July cut while simultaneously satisfying lawmakers that the Fed isn't simply bowing to political pressure? How would he go about doing that?

Well, he would have to talk down the very same economy that Trump is talking up, even as both men are aiming at the same July rate cut (and yes, this is wholly ridiculous). Here's one plan, as detailed by BofA over the weekend:

If the data does not warrant a cut, how can Powell still justify easing? We think there is one angle he can use – he can argue that the reduction in rates is purely to boost inflation and is for “insurance” purposes. He can reference the lower neutral Fed funds rate and argue that the current stance of policy is too tight.

In other words, he could roll out the old standby about "subdued inflation" and then point to the same lower neutral rate mentioned above to argue, as Trump has, that policy is restrictive.

There are a couple of problems with that. For one thing, it would be embarrassing. This is, after all, the same Jay Powell who in October said rates were "a long way from neutral." More importantly, though, it would make an already complicated situation even more difficult to negotiate and it risks irritating markets anyway. Here's BofA:

But this would be yet another shift in the dialogue for Powell, further complicating their reaction function. Moreover, only a handful of Fed officials seem to be on board with this narrative. That said, if the Fed does take this path and cuts in July because of insurance reasons, it would likely imply only a few cuts rather than the start of a true easing cycle. As such, it would still disappoint markets.

So, what will Powell do? My guess is, he'll try to find a middle ground by saying "we will act as necessary to sustain the expansion" as many times as possible and in as many different ways as possible. Of course, there are only so many times you can paraphrase yourself, which means he'll invariably have to elaborate at some point. As we've seen on innumerable occasions since Powell took the reins from Janet Yellen, he is not particularly adept at elaborating.

With the dollar at a two-week high and yields clearly predisposed to rising on any hint that a 25bp cut at the July meeting isn't a sure thing, this is a dangerous situation.

As I hope came through loud and clear in the above, this is complicated immeasurably by the Fed's desire to assert its independence. Following last week's attacks on the Fed, PIMCO's Joachim Fels declared an end to the "heyday of central bank independence." You can read more here, but for our purposes, it's enough to note that Fels predicts central banks will be increasingly beholden to politicians and that will mean low rates and QE in "perpetuity."

Midway through last year, it seemed as though the days of documenting the distortions brought about by ultra-accommodative monetary policy might be behind us - that policymakers were set to finally try and normalize. It is now clear that the "state of exception" (as Deutsche Bank's Aleksandar Kocic called it in 2017) is indeed permanent - or at least semi-permanent.

Last year's cross-asset turbulence made it clear that the re-emancipation of markets isn't feasible from a practical perspective. If PIMCO's Fels is correct (and he probably is), policy normalization is on the verge of being effectively banned from on high.

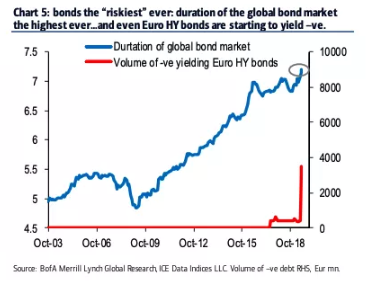

The renewed commitment to accommodative policy is now bringing about outcomes that are not just strange, but wholly oxymoronic. For instance, there are now 10 € high yield bonds with negative yields. And yes, you read that correctly: Some "high" yield bonds are now negative-yielding.

(BofA)

(BofA)

Have a look at the blue line in that visual. That is a whole lot of interest rate sensitivity.

Consider this from Bloomberg:

But just look at the math. The Macaulay duration on a Bloomberg Barclays sovereign-debt index is near a record high of 8.32 years, meaning just a one-percentage-point increase in yields would equate to more than a $2.4 trillion loss.

Even if it were politically possible to raise rates and normalize policy, and even if central banks weren't particularly concerned about the addiction liability they're running in riskier assets, policymakers are now staring down an almost unfathomable pile of duration parked on all manner of balance sheets and not all of it is very liquid.

The upshot of this (now ~2,300 word) screed, is that between politics and market risks, there doesn't seem to be a way to crawl back out of the accommodation rabbit hole. Readers often ask why I refer to Deutsche's Kocic as the most brilliant mind on Wall Street. Well, consider everything said above and then recall the following passages from his 2017 "state of exception" note:

In its core, policy response to the crises was an extension of what in a political context is known as the state of exception: Market laws had to be suspended to restore normal functioning of the markets. The intrinsic contradiction of this maneuver is resolved only by understanding that suspension is temporary. Stimulus will have to be unwound.

However, the accommodation has been in place for a very long time, during which traditional transmission mechanisms have atrophied and investors’ mindset has changed in a way that has altered irreversibly their behavior, the market functioning and its dynamics.

Engineering a state of exception comes with considerable risk. The Fed (and central banks in general) carries an implicit responsibility for orderly re-emancipation of the markets, which makes stimulus unwind especially tricky. This highlights the deep dichotomy of power: While a state of exception is an exercise of power, there is a clear tendency to disown that power. And the only way to avoid facing the underlying dilemma is to never give up the power. This creates a new status quo — a permanent state of exception.

Fast forward two years (almost to the day, as the note those excerpts are from was published in the second week of July, 2017) and the "state of exception" does appear to be permanent.

Strange times, indeed. And, as the occurrence of negative-yielding "high" yield bonds makes clear, things are likely to get stranger still.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario