Negotiations for top European Union jobs point to higher chances of a hawkish tilt in central-bank policy

By Jon Sindreu

The president of the German central bank, Jens Weidmann, is a lead candidate to head the European Central Bank. Photo: Arne Dedert/Associated Press

The battle for the European Union’s top jobs has begun. If the first skirmishes are any guide, the next president of the European Central Bank may be less happy to bail out investors in any future crisis.

Late Tuesday, European leaders held the first of many summits that will determine who heads key EU institutions, including the European Commission—the bloc’s executive body—by the end of October. Negotiations are complicated by the ambiguous results of the weekend’s European parliamentary elections. Neither the big center-right nor center-left parties managed to win a majority, leaving French President Emmanuel Macron’s pro-market centrists as potential kingmakers.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel still wants the commission to be led by Manfred Weber, the German leader of the European center-right party that garnered the most seats in the election. However, she is opposed by Mr. Macron, who has signaled that he will ally with the center-left to push alternative candidates.

The compromise-driven nature of EU politics means that the fight for the commission presidency will likely have direct repercussions on monetary policy.

This is because the presidency of the ECB could emerge as a consolation prize for whichever big country loses the commission bid. Ms. Merkel has always been a vocal advocate of Jens Weidmann, the president of the German central bank and a longstanding critic of current ECB President Mario Draghi. Mr. Draghi led the ECB down the path of monetary stimulus during the eurozone crisis, pledging to “do whatever it takes” to save the euro.

Most European nations think German officials already have too much influence on monetary policy, which is why the Frankfurt-based ECB has never had a German president. This surely won’t change if Germany gets the top job at the Commission.

However, if Mr. Macron’s determination proves strong enough and Mr. Weber’s bid fails, Germany could suddenly be in the running for the ECB. Mr. Weidmann may prove to be too controversial, but Germany has other options. Claudia Buch, the Bundesbank’s vice president, comes with the bonus that she would be the first female ECB president.

A German-led ECB would raise a red flag for investors, who have become used to the central bank under Mr. Draghi coming to their rescue at the first sight of financial turmoil.

To be sure, as long as the eurozone economy continues to experience slow growth and subdued inflation, it is unlikely that any central banker—no matter what nationality or ideological bent—will crank up rates dramatically.

However, investors seem so certain that the ECB will keep rates indefinitely pegged to their current record low of minus-0.4%—and resume bond buying if there is a downturn—that a slight shift in expectations could spark a selloff.

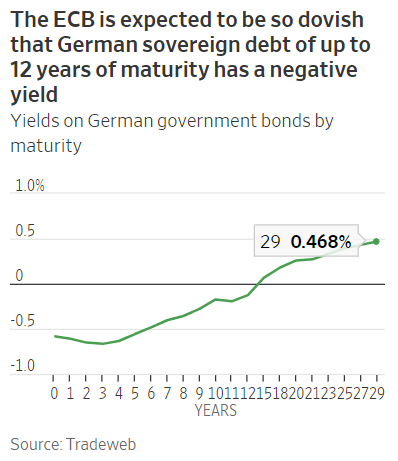

Currently, the yield on German government bonds, the benchmark for all debt in the eurozone, is in negative territory for up to 12 years of maturity.

Negotiations among EU leaders are ongoing and anything remains possible. Compromise candidates like Finns Olli Rehn and Erkki Liikanen may not be of Mr. Weidmann’s bent, but are unlikely to be as generous with the ECB’s balance sheet as Mr. Draghi has been. Only Frenchman François Villeroy de Galhau would imply total continuity.

Bond markets seem to be paying little attention to the current EU horse-trading, perhaps because the outcome is still so uncertain. That is all the more reason for investors to be mindful that a hawkish ECB tilt is a likely outcome.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario