The Only 2 Questions That Count

by: The Heisenberg

Summary

- As markets head for their worst month of the year, investors are asking two questions.

- One relates to the interplay between the economic outlook and central bank policy.

- The other to the assumption that the cost of money and an abundance of liquidity matter more than political ineptitude.

Barring a dramatic turn, May will be the worst month of 2019 for many major global benchmarks.

Indeed, it will likely be the first down month of the year for stocks. The proximate cause is obvious:

The trade war between the world's two largest economies is back on.

The re-escalation of trade tensions rekindled concerns about global growth, and in short order, bonds rallied in a move reminiscent of late-March, only this time, it was less clear that the decline in yields would be a benign development. After the March FOMC meeting, the developed market bond rally (and subsequent spike in the global stock of negative-yielding debt) actually encouraged risk-taking.

The hunt for yield was back and with a Sino-US trade truce still the base case and central banks committed to the dovish pivot, there was little reason to be fearful, although a lack of participation by key investor cohorts (indicative of trepidation after a disastrous Q4 for markets) has been the defining characteristic of the 2019 equity rally.

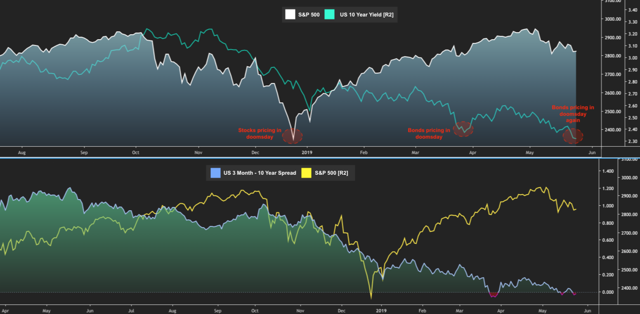

At the time, there was no shortage of commentary regarding the extent to which bonds were telling a different story than stocks (and that's to say nothing of the curve, where the 3-month-10-year inversion precipitated the usual recession chatter). Barclays summed things up nicely in a March note:

Ancient cultures looked wonderingly at the sun and moon, at the wind and tides, and ascribed god-like properties to explain away natural phenomena. Modern investors sometimes adopt this approach in periods of financial stress as they parse the message from an all-knowing "market." In the throes of last December's equity downturn, we were repeatedly asked what the "market" was saying about the economy. Three months later, equities have roared back. But the US 3m10y yield curve inverted, while 10y bunds traded through 0bp. Sure enough, the questions have come back. What, the query goes, is the "market" telling us about the economy? The difference, of course, being that the all-knowing property of stocks has now moved to bonds.

Below is a visual that illustrates all of those points, although I doubt you need it.

(Heisenberg)

In the same note, Barclays suggested that the reality of the situation is less dramatic than any headlines alluding to "messages" from the markets. "The global expansion should continue for the foreseeable future, and we do not see any major economy growing below trend in 2019", the bank wrote, adding that "if equity markets were too pessimistic about the economy late last December, bond markets have taken up that mantle now."

Again, that was in March. Fast forward to May and the rally in bonds looks less benign when it comes to the read-through for risk assets. You don't want to chase down the quality ladder and out the risk curve if you think the global economy is headed over a cliff, no matter how unpalatable it is to forgo carry or settle for the meager (and in some cases negative) yields on safe havens. Especially not when USD "cash" is still an attractive proposition.

The question, then, is whether the prospect of a prolonged trade conflict featuring more escalations and retaliations is enough to completely invalidate a constructive take on risk assets predicated on the continuation of central banks' dovish pivot. This is a familiar question, and the most important concept to grasp when you consider it is that growth jitters and the perception that events beyond monetary policy's control are weighing on the outlook are a necessary condition for adopting an easing bias. If the problem for risk assets in 2018 was monetary tightening, not geopolitical turmoil, then a darkening outlook for global growth is paradoxically a positive development to the extent it ensures that central banks press pause on normalization. Here's how I put it on Sunday evening:

What really matters for risk appetite? Is it the price of money and the promise of abundant liquidity, or the perception that politicians are inept?

Most readers will probably say it's the former. Especially considering that, if there's anything everybody can agree on in an increasingly polarized political environment, it's that politicians as a group have been prone to ineptitude from time immemorial. In other words, if political tumult, geopolitical bickering, and partisan gridlock have always been a fact of life for investors, then the current climate is really no different than it's been in the past. I don't believe that's an accurate assessment, but the point is simply to say that unless there's some kind of catastrophe (and remember, actual catastrophes are impossible to hedge), it's real rates and liquidity that matter. Consider these excerpts from a Deutsche Bank note dated Friday:

Equities have learned how to thrive in such environments. After all, we had almost a decade of sub-average growth and problematic recovery when excess accommodation pushed equity performance to near all-time highs. As if all equities need is excess liquidity (for the same reason, stocks have perceived rate hikes as the most significant headwinds). Thus, it comes as no surprise that the current equity repricing hasn't been accompanied by a rise in vol risk premia. One way or another, the market seems to believe that equities would be all right - either the trade war risk is diffused or, in the case of its deepening, there is an accommodative Fed on the sidelines.

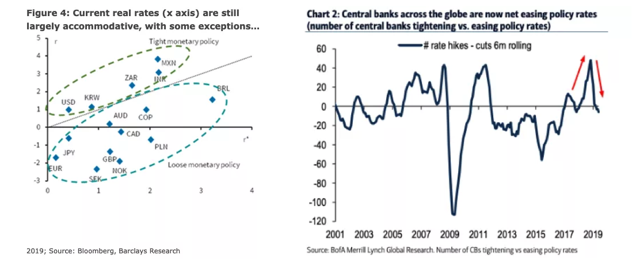

With that in mind, consider the pair of visuals below which show, on the left, how loose monetary policy is across economies and, on the right, the difference between the number of central banks hiking rates and the number cutting rates on a rolling six-month basis.

(From left: Barclays, BofA)

The point is that policy is accommodative across most locales, and central banks are, on net, back to a bias to ease. That bias is likely to get stronger going forward (for instance, the RBA is widely expected to start cutting rates imminently).

Of course, there's a fine line between the type of economic weakness that prompts a market-friendly policymaker pivot and the kind of outright downturn that sparks aggressive rate cuts and emergency monetary policy. In the latter case, the policy response is seen as a reflection of the severity of the problem rather than as a boon to risk assets. This is why it's critical that central bankers avoid "confirming" the market's worst fears when communicating the rationale for dovish pivots.

As things stand, the global economy doesn't appear to be in the kind of dire straits that bond yields would suggest, although the situation in Germany (i.e., the ongoing manufacturing slump) and the most recent data out of China do not bode particularly well. As long as the situation doesn't deteriorate to the point where central banks' accommodative bias is viewed as indicative of policymaker panic, dovishness should carry the day for risk assets.

However, it's worth noting that because the Fed had already completed a hiking cycle while its global counterparts were still sitting with bloated balance sheets and record low rates, Fed policy will remain relatively hawkish. That's especially true as long as Powell refrains from active easing (e.g., actual rate cuts) while the ECB rolls out a new round of TLTROs, the RBA cuts rates, etc. That relative hawkishness combined with the outperformance of the US economy means the dollar can remain supported. Of course, a stubborn dollar in the face of a trade war is a dangerous mix. Here's Nomura's Charlie McElligott:

…global trade is clearly now being dragged into the mud by a 'vicious spiral' of not just the actual tariff barriers and the lack of corporate visibility therein, but perhaps most importantly, the ongoing strength in the US Dollar, which further undermines a global economy which is dependent upon trade and financed by US Dollar liquidity.

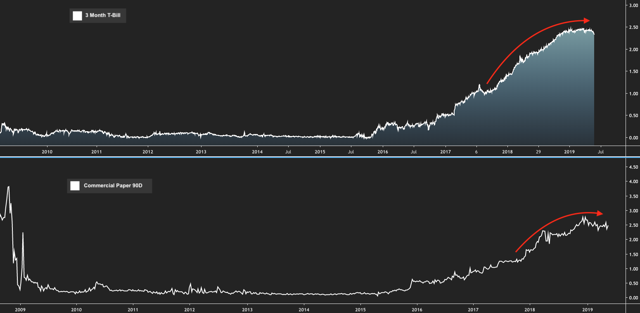

The "dollar shortage" story, I warned last week, has "lingered like stale cigarette smoke", despite the Fed's efforts to loosen financial conditions.

The risk, then, is that as long as the rest of the world is easing too, the Fed simply can't ease enough to prevent a return of the dynamics that plagued markets in 2018 when USD "cash" outperformed 90% of global assets. As McElligott went on to remind you, it's "still pretty tight out there". Here's an illustration:

(Heisenberg)

At the end of the day, it's all about answering two questions. The first is whether the outlook for the global economy remains just bad enough to keep monetary policy cautious in perpetuity, but not so bad as to prompt a panic. The second is whether low rates and excess liquidity will everywhere and always render "politicians' implied vol." (if you will) null and void.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario