A Tail Risk The Fed Can't Solve

by: The Heisenberg

Summary

- The latest edition of one bank's closely-watched fund manager survey shows a wholly unsurprising top tail risk.

- Although the pros are worried about the right thing, and have apparently taken out portfolio hedges, the level of concern seems inadequate.

- That goes double when you consider there's no credible monetary policy response to a worsening of trade tensions.

- Although the pros are worried about the right thing, and have apparently taken out portfolio hedges, the level of concern seems inadequate.

- That goes double when you consider there's no credible monetary policy response to a worsening of trade tensions.

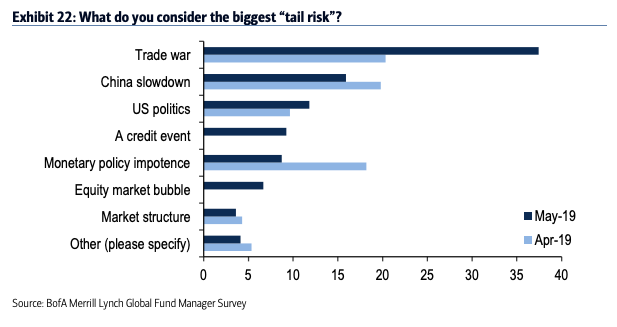

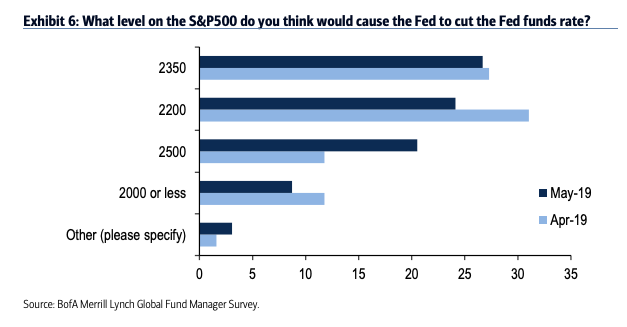

In the latest edition of Bank of America's closely-watched Global Fund Manager survey, the number one tail risk is "trade war".

"That's no surprise given the survey was taken May 3rd-9th, but trade war concerns are well below levels seen last summer," the bank's Michael Hartnett wrote this week.

Here's the visual which illustrates Hartnett's point:

(BofAML)

When you consider that "China slowdown" worries are in part a manifestation of the trade war, it's fair to say that global fund managers have identified the trade conflict as the top tail risk for 14 of the last 15 surveys. The latest edition tallies results from a total of 250 respondents, who together manage nearly $700 billion in AUM.

Hartnett's point about conviction in what the top tail risk is not being as high as it was last summer might seem trivial, but it's not. Note that last August, some two thirds of respondents identified "trade war" as the biggest tail risk. That figure was just 37% in May.

(BofAML)

(BofAML)

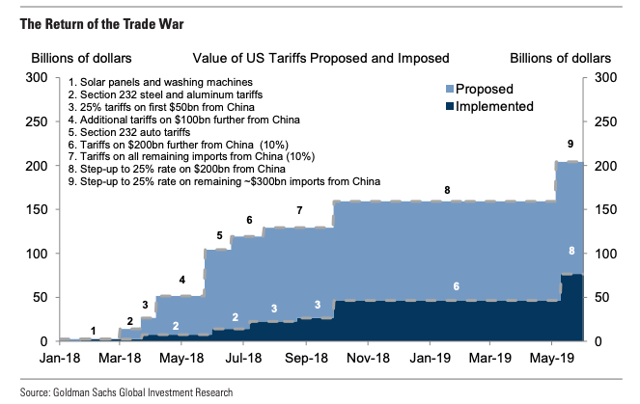

Since August, there have multiple escalations between the US and China, including, of course, the Trump administration's recent decision to more than double the tariff rate on $200 billion in Chinese goods, China's subsequent threat of retaliation, the specter of tariffs on all Chinese exports to the US and, on Wednesday, the de facto banning of Huawei.

To be fair, the survey period noted above doesn't capture the Huawei news and it also misses another week of losses for the yuan, but the point is, the relative sanguinity (versus last summer) looks misplaced to me.

On Friday, I spent some time writing a lengthy post for this platform outlining why some believe the Huawei news might have been the straw that broke the camel's back for the trade talks. Not everyone agrees with that assessment. The US election in 2020 raises the stakes for the Trump administration and one might well argue that the US president wouldn't risk the talks with China collapsing (or an all-out trade war) for fear of economic blowback and what a falling stock market would mean for his reelection bid. That said, I continue to believe the calculus is more complex than that.

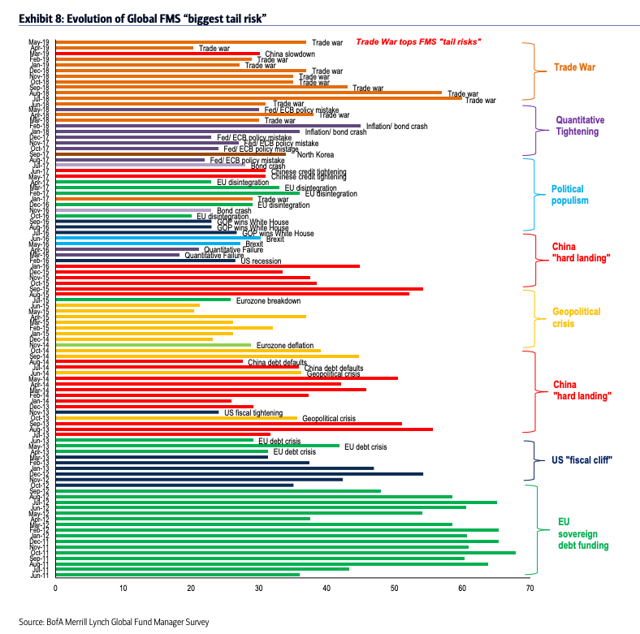

In any event, respondents to BofA's survey believe the vaunted "Fed put" (in this case, the level at which the Fed would actually cut rates, although it's not necessary to conceive of the Fed put as manifesting itself in overt easing) is struck some ~22% below the highs.

(BofAML)

That's probably too extreme. That assumes the Fed put wasn't re-struck higher following the December lows (i.e., that it still corresponds to an SPX beta of roughly 10 to the short rate). I doubt that's the case. That is, the Fed put isn't 20% out of the money. "Between June and December of 2018, the S&P followed a beta = 23 trajectory," Deutsche Bank wrote in a Friday note, adding that "when the market tested the Fed's resolve and sold off almost all the way to the [previous] put strike... a subsequent dovish Fed response [led to] a recovery of stocks all the way back to current levels." Assuming the beta = 23 trajectory, the Fed put is likely around S&P 2600.

The problem with even talking about the Fed put right now is that the central bank would arguably be wading into dangerous waters by cutting rates in response to trade-related market frictions. It's true that past a certain point, stock price declines serve to tighten financial conditions, and widening credit spreads exacerbate the situation, ostensibly calling for a monetary policy response. Right now, though, Fed cuts in the context of an escalating trade war could well encourage further escalations, as competitive easing emboldens politicians on both sides of the dispute to push the envelope knowing they have monetary policy cover. Those additional escalations could eventually snowball until tit-for-tat protectionism manifests itself in rising consumer prices and lower growth. At that juncture, monetary policy is constrained on the easing side by higher inflation and on the tightening side by slowing economic activity.

Meanwhile, the credibility of a central bank which participates in a trade war will have been damaged.

There's more on the Fed put and the quandary described above here, but suffice to say there aren't many good options when it comes to a monetary policy response should trade frictions get worse.

Therefore, the better outcome would be for stock price declines to be seen by politicians as the market sending a message about the extent to which protectionism is injurious to businesses and a potential headwind to growth and economic prosperity. If that message is accepted, tensions will ease and the odds of a trade truce increase, obviating the need for the Fed to respond at all.

It's important to remember that up until the latest escalation (i.e., the doubling of the tariff rate on the $200 billion in Chinese goods that were originally taxed at 10% from September 24), the trade war hasn't really had much bite (so to speak) in terms of a quantifiable, direct economic impact. As Credit Suisse wrote last month, the "fear" of trade tensions was actually more impactful than any mechanical effect.

But that will change if the entirety of Chinese exports to the US are hit with levies and if, after a delay, the Trump administration moves forward with auto tariffs. How many commentators were sure last summer that this would all die down in relatively short order? Quite a few, if not the majority.

Well, it hasn't died down. Both the value of proposed tariffs and the value of implemented levies keeps ratcheting higher.

Remember, roughly 30% of S&P 500 COGS are imported. Given that and given the impossibility of overhauling globalized supply chains overnight, it is a mathematical certainty that if these tariff escalations keep coming, profits will be lower, prices will be higher, or some combination of both.

The only way that doesn't play out is if you assume a wholly unrealistic combination of higher domestic revenues (which implicitly counts on the current expansion continuing) and efficient supplier substitution. That best-case scenario which avoids margin compression and price hikes is, to my mind anyway, far-fetched in the extreme.

Meanwhile, the impact of further escalations will ricochet across the globe in classic fashion.

Here's BNP, from a note out Friday:

In the medium term, higher tariffs imply reduced competition, lower productivity and inefficient distribution of resources – i.e., a negative supply shock. In the short term, recent developments’ key impact is likely to come from a reduction in global trade and persistent uncertainty, deterring investment, encouraging precautionary savings and possibly affecting the markets through higher risk premia.

Again, this will become unavoidable at some point, and as detailed above, there won't be a Fed response that doesn't come with considerable risk.

Coming full circle to the BofA fund manager survey, consider one final excerpt that drives all of this home rather poignantly:

34% of FMS investors say they have taken out protection against a sharp fall in equity markets over the next three months, the highest level ever on an absolute and net basis (net -21% say they have taken out protection).

At least folks are well-protected.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario