NATO at 70

How NATO is shaping up at 70

The Atlantic alliance has proved remarkably resilient, says Daniel Franklin. To remain relevant, it needs to go on changing

REACHING 70 IS an extraordinary achievement for the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation. Most alliances die young. External threats change; national interests diverge; costs become too burdensome. Russia’s pact with Nazi Germany survived for only two years. None of the seven coalitions of the Napoleonic wars lasted more than five years. A study in 2010 by the Brookings Institution, a Washington think-tank, counted 63 major military alliances over the previous five centuries, of which just ten lived beyond 40; the average lifespan of collective-defence alliances was 15 years.

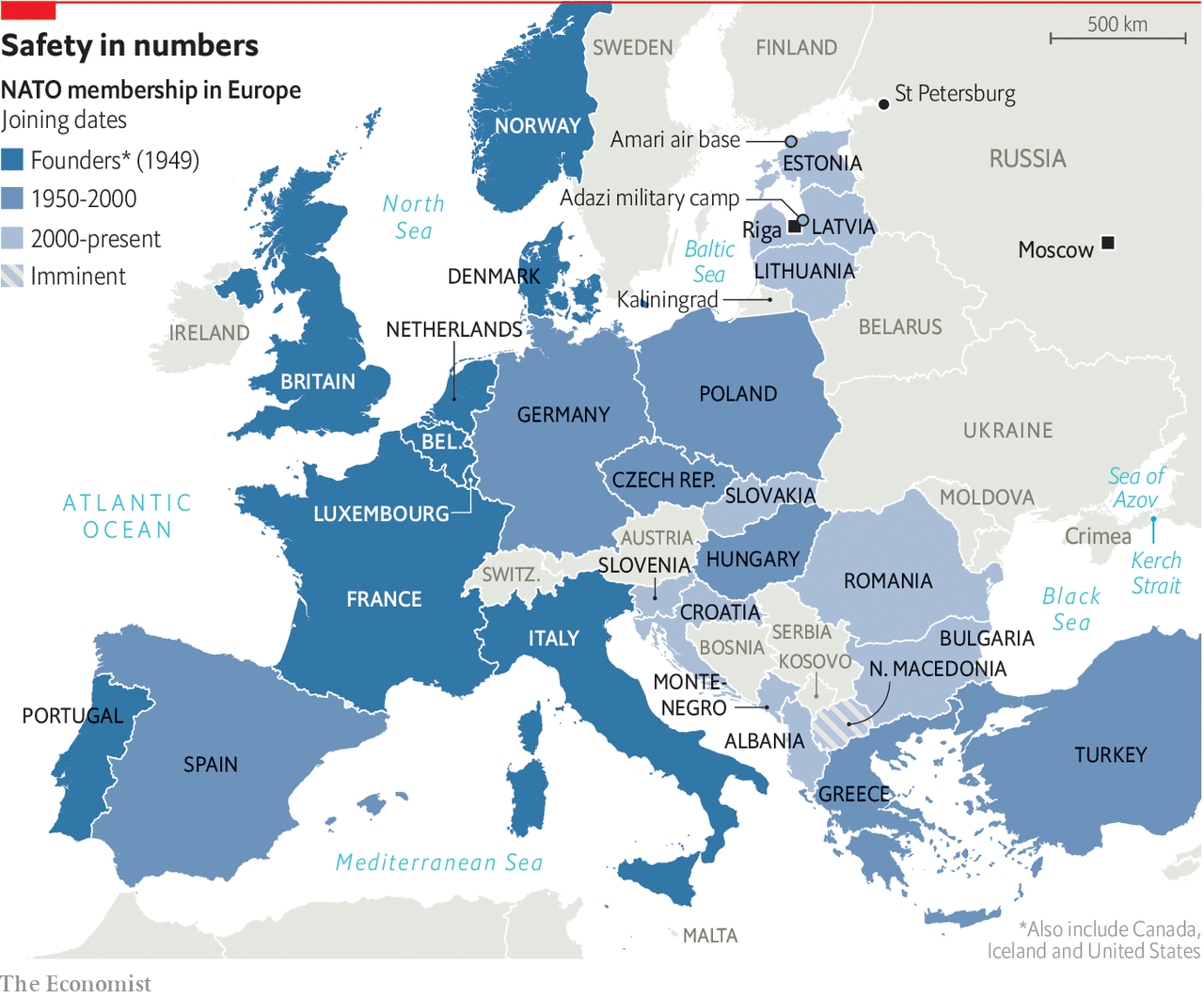

“NATO is the strongest, most successful alliance in history”, says Jens Stoltenberg, the organisation’s secretary-general, “because we have been able to change.” It has expanded from 12 members at its birth to 29—soon to be 30 when North Macedonia joins, its dispute with Greece over its name now settled. Of the eight countries that made up its erstwhile rival, the Warsaw Pact, seven have become part of NATO, as have three former Soviet republics. The eighth one, the Soviet Union itself, has ceased to exist.

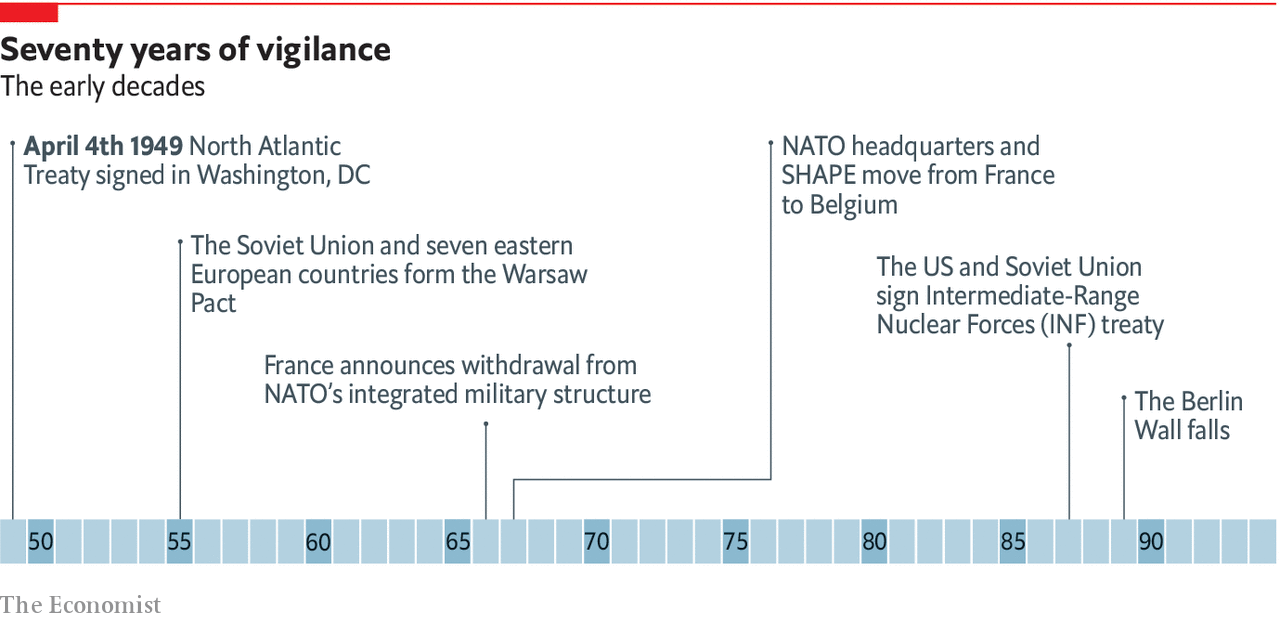

For its first four decades NATO was busy deterring the Soviet threat. Its role was to keep “the Russians out, the Americans in and the Germans down”, as its first secretary-general, Lord Ismay, put it. But after communism collapsed, the alliance did not proclaim victory and shut up shop; instead it reinvented itself, helping to stabilise the new democracies of eastern Europe.

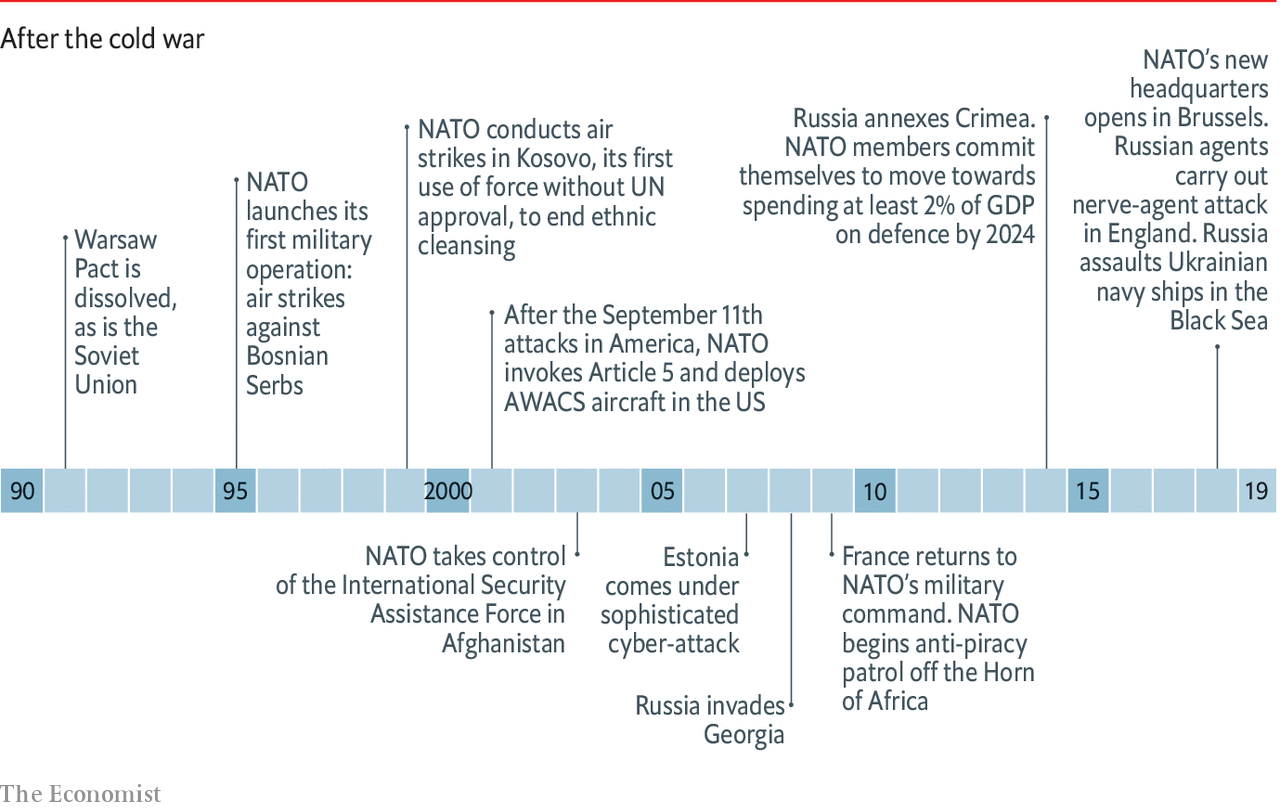

Realising that it needed to go “out of area or out of business”, it then embarked on a period of far-flung crisis-management, from the Balkans (with interventions in Bosnia and Kosovo) to the Horn of Africa (where an anti-piracy mission ran from 2009 to 2016) and Afghanistan (where it still leads some 16,000 troops in Operation Resolute Support). NATO’s founders would have been stunned by such mission creep—as well as by the circumstances in which Article 5 of its treaty, which says that an armed attack against one member will be considered an attack against them all, was put to use. The only time the allies invoked this pledge was on September 12th 2001, the day after al-Qaeda’s terrorist attacks on America.

After Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 the alliance moved swiftly back to its core business of deterrence against its eastern neighbour. Now for the first time it is having to juggle invigorated collective defence and crisis management simultaneously. At 70, it is hardly settling for an easy life.

Its birthday celebrations will be modest: just a one-day gathering of foreign ministers on April 4th in Washington, DC, where the North Atlantic Treaty was signed in 1949. NATO wants to avoid a repeat of the bruising confrontations that took place at its summit in Brussels last July, where America’s president, Donald Trump, berated his allies for not pulling their weight on defence. If they did not shape up, he said, his country might go its own way. Another damaging row is the last thing the organisation needs as it struggles with intimations of its own mortality. “We don’t have a guarantee that NATO will survive for ever,” says Mr Stoltenberg.

At times Mr Trump has seemed to suggest that he would be happy to see it die. On the campaign trail he called it “obsolete”. Once in office, he initially avoided backing its collective-security pledge; instead, he seemed to regard NATO as just another deal, in which American taxpayers were getting ripped off. In January the New York Times reported that several times last year he privately said he wanted to pull the United States out of NATO. Such reports only fuel fears that he might be doing Russia’s bidding. Mr Trump calls these suspicions “insulting”.

If he were to decide to abandon NATO he would face resistance in Congress, where bipartisan support for the alliance remains strong and control of the purse strings powerful. A record number of more than 50 senators and representatives attended the Munich Security Conference last month to show solidarity. Last July the Senate voted 97-2 to back NATO. In January the House of Representatives voted 357-22 in favour of the NATO Support Act, which would prohibit any use of federal funds for withdrawal. Though heartening for NATO, these votes highlight the sense of threat hanging over it.

Yet its pharaonic new headquarters on the outskirts of Brussels projects the permanence of an organisation preparing for its next 70 years, not one about to perish. Opinion polls show solid public support for NATO in its member countries (with the significant exceptions of Turkey and Greece). Even in America, despite Mr Trump’s attacks, 64% of those polled by Pew Research Centre are favourable towards NATO, up from 49% in 2015, and a survey last year by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs showed that more Americans than at any point since polling began in 1974 favour increasing their country’s commitment to the alliance.

NATO optimists offer three reasons for not fretting too much over Mr Trump. First, NATO is no stranger to crises, from Suez in 1956 to France quitting the integrated military command in 1966 and splits over the Iraq war in 2003. It has a record of resilience.

Second, they point out that since becoming president, Mr Trump has said that the alliance is “no longer obsolete”, that he is “committed to Article 5” and that America will be “with NATO 100%”. True, he continues to lambast his allies for failing to pay their fair share of their own defence, but on this matter his bullying is justified and useful: the allies do need to spend more.

Their third and strongest argument for remaining sanguine about Mr Trump is based on his deeds rather than his tweets. On his watch America has increased, not decreased, its defence efforts in Europe, with more equipment, more troops and more money. Funding for America’s military presence in Europe, under what is called the European Deterrence Initiative, has risen by 40%.

This is part of NATO’s determined response to the increased threat from Russia. At summits in Wales in 2014, Warsaw in 2016 and last year in Brussels—even as the world focused on Mr Trump’s bolshiness—the allies took a series of decisions designed to restore robust territorial defence. They created a Very High Readiness Joint Task Force, prepared to move within days, and put combat-ready multinational battlegroups into the three Baltic countries as well as Poland. They committed themselves to a costly “Four 30s” initiative, with the aim of having 30 mechanised battalions, 30 air squadrons and 30 warships ready to move in no more than 30 days by 2020. To ensure swift movement of forces, they planned two new commands, in Norfolk, Virginia, and Ulm in Germany.

Last autumn NATO tested its capabilities in Trident Juncture, its biggest exercise since the end of the cold war, which involved some 50,000 people in and around Norway. Gaps remain, but the erosion of defence capacity that NATO had allowed as a peace dividend after the collapse of communism is being reversed.

This special report will run a health check on NATO. It will assess the alliance’s chances of surviving through its 70s and consider how it needs to change in order to remain vigorous to 100. In the short term the wild card remains Mr Trump. For two years the allies were reassured by the presence around him of NATO-friendly “adults in the room”, especially generals such as James Mattis, the defence secretary. These grown-ups could not prevent transatlantic rows over trade and the nuclear deal with Iran, which Mr Trump has abandoned, but they could exercise some restraint. They are now gone; Mr Mattis quit in December. His resignation letter pointedly stressed the importance of “treating allies with respect”.

Even without Mr Trump, however, the cohesion and the democratic values that the alliance is supposed to share are under strain. It can still summon up solidarity, for example in response to Russia’s nerve-agent attack on Sergei Skripal, a Russian ex-spy, and his daughter Yulia in Salisbury in England. But divisions among the Europeans look worryingly wide.

Britain, usually a NATO stalwart, is consumed by Brexit, and might even elect a seasoned NATO-basher, Labour’s Jeremy Corbyn, as its next prime minister. Nationalist governments in Hungary and Poland are at odds with their EU partners. France’s relations with Italy sank so low that it recently recalled its ambassador.

Relations between America and strategically critical Turkey, which will soon be overtaking Germany as NATO’s second-most-populous country, have been strained, too. Turkey’s plan to buy a Russian air-defence system is a sore topic in Washington. The two countries have also been at odds over Turkey’s detention of an American pastor (now released) and over America’s refusal to extradite a Turkish cleric, Fethullah Gulen, whom President Recep Tayyip Erdogan blames for an attempted coup in Turkey in 2016. And they disagree over the fate of Kurds in Syria who fought alongside America but are seen as terrorists by Mr Erdogan. If relations were to sour badly, America could “devastate Turkey economically”, Mr Trump has said. Both sides seem to be working to avoid that.

These are not the best of times for the allies to be tackling an issue as thorny as intermediate-range nuclear forces (INF). On February 1st America pulled out of the 31-year-old INF treaty banning land-based missiles with a range of 500-5,500km, in response to what it called clear Russian violation. NATO has backed America’s move, but the issue threatens to become as fraught as when American cruise and Pershing II missiles were being deployed in Europe in the 1980s to counter the Soviet Union’s mid-range nuclear arsenal. Now, as then, there is a risk of holes in America’s nuclear umbrella that could leave the European allies vulnerable.

Look farther east

NATO has been very effective for 70 years, says Mike Pompeo, America’s secretary of state, who will host the anniversary meeting in Washington, “and we want to make sure that it continues to be effective for the next 70 years.” That will not be easy. The tectonic plates of geopolitics are shifting. A return to great-power rivalry is in prospect. Although Russia has a potent nuclear-tipped military force and an opportunistic willingness to disrupt the status quo, in the long run it is seen as a declining power. The emerging giant is China. The old Soviet Union peaked at less than 60% of America’s GDP and a population about a fifth bigger. In China, America faces a rival that has four times as many people and will soon outstrip its economy. As China rises, challenging America’s interests around the world, it will take up ever more of America’s attention and resources. That process started before the Trump presidency, and will continue and intensify far beyond it.

How can the transatlantic alliance hold together as America becomes less focused on Europe and more immersed in Asia? That is a vital question, but so far NATO has barely started tackling it.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario