With little room to tweak economic policy, what happens in Europe increasingly depends on political decisions in Beijing

By Mike Bird

A barricade prevents access to Tiananmen Square from an underpass in Beijing, China. Photo: Giulia Marchi/Bloomberg News

This week, technocrats and functionaries gathered to discuss economic policy, making decisions that will determine the near-term prospects of the eurozone economy.

Also, the European Central Bank’s governing council held a meeting.

For a steer on the currency union’s growth prospects, investors would be better off analyzing the output of China’s 13th National People’s Congress than that of Europe’s monetary policy makers. The ECB said Thursday it would hold interest rates at current levels for at least the rest of 2019, and issue new cheap long-term loans for banks in the second half of the year.

Beyond its current effort, there is little the ECB can do in the face of an economic slowdown. It could restart an all-out quantitative easing effort, but that would involve abandoning self-imposed restraints on which government bonds it can buy.

Nor will national governments ride to the rescue. The bloc’s fiscal rules prevent countries like France and Italy from pursuing meaningful stimulus. In Germany, the country with most room to pursue debt-funded spending, arguing for a sustained increase in borrowing is political anathema.

That leaves the bloc, particularly its largest economy, increasingly at the mercy of decisions made not in Brussels or Frankfurt, but in Beijing.

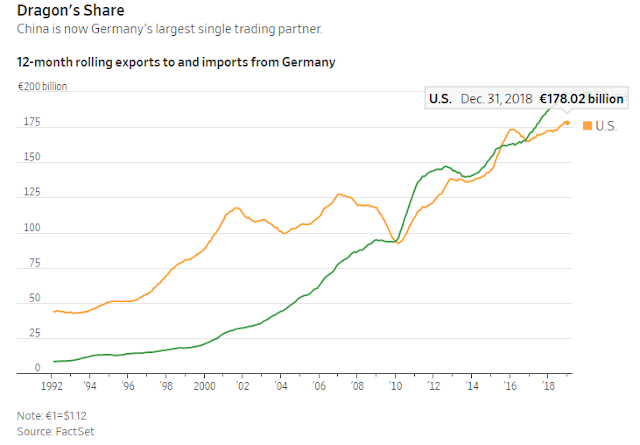

In 1991, U.S. trade with Germany was about five times as large as China’s equivalent figure. Now, the Middle Kingdom is Germany’s largest single trading partner. Even that understates the importance of the connection. China’s place in inter-Asian trade means that a slowdown there impacts German exports to countries such as South Korea too.

A boom in German exports to China as Beijing pursued huge stimulus after 2008 was a major reason why the economy recorded such strong growth relative to its peers. Conversely, China’s slowdown in 2015 and 2016 helped push the eurozone into a period of deflation that sparked the ECB to begin a QE program. More recently, German exports to China fell 7.7% year-over-year in December, the weakest figure in almost three years.

So far, the message from the National People’s Congress has been muddled: Chinese policy makers want to simultaneously keep debt levels in check while boosting borrowing to private companies.

The headline from the congress—the lowering of China’s growth target to a range of 6% to 6.5% this year—should, though, alert investors that major external support for the eurozone isn’t likely soon. Even the stimulus measures Beijing has taken to date are unlikely to feed through until later this year. If the ECB’s lack of firepower is worrying, the fact that China won’t ride to Europe’s rescue this time is chilling.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario