The Cold War in Tech Is Real and Investors Can’t Ignore It

By Reshma Kapadia

Cisco Systems, an early Silicon Valley success story, has become one of the nation’s top tech exporters. Today, roughly half of the networking giant’s sales come from outside the U.S. As foreign countries sought to catch up with U.S. connectivity, Cisco helped plug them in.

But a wave of nationalist thinking has put Cisco (ticker: CSCO)—and most of its peers—in an uncomfortable position. Earlier this month, Cisco CEO Chuck Robbins described the current climate as “one of the more complex macro, geopolitical environments that I think we’ve seen in quite a while with all the different moving parts.”

It’s likely to get worse.

While investors are cheering indications of progress being made toward a resolution of trade issues between China and the U.S., the battle for tech supremacy between the two global superpowers shows few signs of abating. Even as the White House was negotiating on trade with Beijing, it was also contemplating a U.S. ban of telecommunications equipment from Chinese companies like Huawei Technologies, essentially China’s version of Cisco. As President Donald Trump was tweeting about the importance of 5G on Thursday, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo was pushing U.S. allies to ditch Huawei.

This is a fight that is not going to end anytime soon. For years, U.S. officials have worried about Chinese equipment being used to infiltrate U.S. networks and businesses for possible espionage and theft of intellectual property. Even a resolution of the trade war won’t quell those fears.

“The perception is that too much of the information- and communication-technology supply chain is centered on China,” says Paul Triolo, who focuses on global technology policy issues for risk consulting firm Eurasia Group. “If we are in a conflict and using infrastructure built by China, they could theoretically hit a button and shut off everything.”

“After 30 years of saying companies should optimize supply chains and move some abroad, now we are saying it’s a security concern,” he says. “Adjusting to that is jarring.”

WELCOME TO THE NEW COLD WAR IN TECH.

For a short period last year, the Trump administration banned U.S. exports to Chinese telecom equipment maker ZTE(763.Hong Kong). Unable to get crucial components from U.S. suppliers, ZTE’s production was crippled, and its stock fell 40%.

The move had collateral damage, including U.S. optical networking company Acacia Communications(ACIA), whose own stock fell 35% in the days after the ban. Ultimately, President Trump reversed the ban and fined ZTE $1 billion instead.

Last August, Australia banned Huawei gear from its 5G networks. In January, the Australian wireless and internet company TPG Telecom(TPM.Australia) scrapped its plan to build a new mobile network, citing the ban. TPG shares are down 29% since late August.

For investors, these are early previews of the dangers to tech companies as their parent nations are pulled between the U.S. and China. Consider that Flex(FLEX), Broadcom(AVGO), Qualcomm(QCOM), Micron Technology(MU), Intel(INTC), and Qorvo(QRVO) each sold Huawei more than $90 million of equipment in 2017, the last full year of data, according to Gavekal Research analyst Dan Wang. All of those sales could be imperiled by a Huawei export ban that has been discussed by the Trump administration. For investors, a ban is a greater risk than the cyclical slowdown already weighing on the chip industry.

At the same time, China is no longer content to be the world’s factory for low-cost goods, pushing its own homegrown companies to challenge the global positions of established tech leaders. For China, technology is central to its ambitions to be a global power, a topic that goes well beyond trade agreements.

Western Europe is already caught in the middle. Ostensible U.S. allies are being pressured by the Trump administration to take a tough line with privately held Huawei. European telecom operators, however, have spent years buying Huawei gear. Vodafone, a top United Kingdom telecom provider, has temporarily banned Huawei from the most critical parts of its network. But both Germany and the U.K. are leaning against an outright ban, The Wall Street Journal has reported.

The U.S., meanwhile, has stepped up its crackdown. In December, at the request of the U.S., Canada arrested Huawei Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou on charges of bank and wire fraud. The company has repeatedly denied those charges as well as spying allegations. Huawei did not respond to requests for comment.

Huawei has become a major player in the telecom space by undercutting rivals like Cisco and Nokia(NOK). The Shenzhen-based company’s revenue has risen to an estimated $109 billion last year from $18 billion in 2008.

“We have experienced price-focused competition from competitors in Asia, especially from China, and we anticipate this will continue,” Cisco warned in its latest annual report.

Congress has introduced bipartisan bills to ban the sale of U.S. chips and components to Huawei and other Chinese telecom companies breaking the law or violating sanctions. Lawmakers finding common ground on the issue illustrates the magnitude of the threat, which has been complicated by U.S. companies turning to China’s 1.4 billion consumers for growth.

Lately, however, U.S. companies have felt the pain of more-insular Chinese consumers, who have been encouraged to buy local goods. China weakness was the focus of Apple’s rare revenue warning earlier this year.

Mergers are another likely casualty, as the U.S. and China each add new reviews of cross-border deals. Last year, the Trump administration blocked chip maker Broadcom, then based in Singapore, from buying Qualcomm because of its Chinese connections. Qualcomm dropped its own bid for NXP Semiconductors (NXPI) of the Netherlands last year after China’s review board, the State Administration for Market Regulation, dragged its feet. In its latest annual report, Qualcomm warned that “future acquisitions may now be more difficult, complex, or expensive to the extent that our reputation for our ability to consummate acquisitions has been harmed.”

China’s investments in the U.S. fell to less than $5 billion last year from $46 billion in 2016, according to Rhodium Group.

Illustration by Edel Rodriguez

The shifting dynamic is a costly distraction, at best, as tech companies come up with contingencies and look to shift production out of China. But the real worry is that as the U.S. and China try to protect their own interests, they may take down the entire tech ecosystem along with all of the innovation it produces.

Wall Street’s tech analysts can’t model for an end to innovation. But that doesn’t mean investors should dismiss the risk.

“It’s absolutely something we have to think about in terms of the assumptions we are making about revenue and margins,” says Steve Smigie, senior investment analyst for GQG Partners, which oversees nearly $19 billion.

Take Huawei. If the company is hit with an export ban similar to the one imposed on ZTE, Wang of Gavekal Research says the company would be unlikely to survive. While a collapse might be seen by U.S. officials as a cold war victory, it would reverberate throughout the global economy. Huawei has six times the sales of ZTE, and its gear is used in 170 countries.

While the tech cold war remains largely theoretical, Barron’s spoke to policy watchers, fund managers, and industry analysts to come up with a basket of stocks already feeling effects from the tech battle.

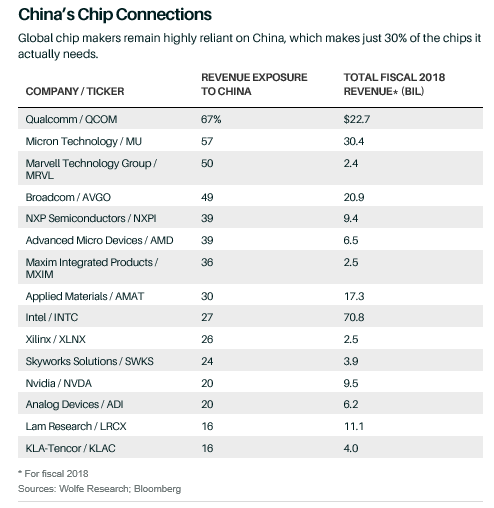

THE HARDEST HIT: CHIP STOCKS

Semiconductor chips are the brains for just about anything with an on-and-off switch. Chips also happen to be the Achilles’ heel for China, making them a major battleground in a tech cold war. Despite several pushes in past decades to create its own semiconductor industry, China makes just 30% of the chips it needs, according to a report by Deloitte.

Chip stocks had a rough fourth quarter last year, hit by concerns about tariffs and a cyclical downturn. The PHLX Semiconductor Index has rebounded 17% to start the year.

The threat of export restrictions, however, still looms over the industry. “It has made it extremely hard to have conviction on a lot of these names,” says John Vinh, an analyst with KeyBanc Capital Markets, who has a Sector Weight on much of the industry he covers. “The ban on ZTE had a ripple effect through the chip industry. A ban against Huawei would have a much more significant impact. I would be cautious on any trade deal. China still has issues that we wouldn’t be out of the woods on, even if there is a resolution.”

THE MOST TO LOSE: MICRON TECHNOLOGY

Micron, the No. 1 memory chip maker in the U.S., is one of Huawei’s suppliers and would be in the crosshairs of any export ban. Even absent a ban, Micron will struggle as China tries to reduce its reliance on U.S. suppliers.

Analysts estimate that China is at least five years away from chip independence, but it is having initial luck on lower-end chips, like the flash memory used in smartphones. Since the focus is on building self-reliance, not necessarily profitability, China’s chip push could spell pricing-related trouble for entrenched rivals like South Korean giants Samsung Electronics(005930.Korea) and SK Hynix(000660.Korea), and U.S.-based Micron. Micron is less diversified than Samsung and could also lose out if China begins to favor Asian suppliers to hedge its bets. Micron declined to comment on China’s chip initiatives.

The company has publicly told investors that competition always exists and that the China threat is nothing new. In its annual filing, however, Micron includes the following risk: “The threat of increasing competition as a result of significant investment in the semiconductor industry by the Chinese government and various state-owned or affiliated entities that is intended to advance China’s stated national policy objectives. In addition, the Chinese government may restrict us from participating in the China market or may prevent us from competing effectively with Chinese companies.”

While Micron benefits from long-term trends around artificial intelligence and autonomous cars, Goldman Sachs chip analyst Mark Delaney recently warned in a note that memory pricing broadly could deteriorate another 20% or more in the first quarter, with further declines in the second quarter. He recently cut his 2019 earnings estimate by 14%, to $6.27 a share. At a recent $43, Micron is already one of the cheapest stocks in the S&P 500 index based on next year’s consensus earnings estimates. But the U.S.-China dynamic makes even this cheap stock a risky bet.

WELL POSITIONED: HUAWEI’S COMPETITION

Huawei has spent several years challenging the established network infrastructure players like Cisco, Nokia, Ericsson(ERIC), Ciena(CIEN), and Juniper Networks(JNPR). Any move away from Huawei, therefore, would benefit these companies.

Their routing and switching gear sit in the core of telecom networks where traffic is aggregated—the very area that intelligence experts fear could be targeted by Chinese spyware.

“We believe over a third of the mobile infrastructure and software market that IHS values at $47 billion in 2019 presents a battleground along with the nearly $15 billion routing and optical markets,” Raymond James analyst Simon Leopold wrote to clients last month.

Cisco is the safe play and would be a winner if the Trump administration follows through on an executive order banning Huawei from U.S. 5G networks. Huawei products are already limited in the U.S., but a ban could spur European allies to take similar steps, and their networks use Huawei.

Cisco has an additional advantage over its rivals. The company only gets about 3% of its sales from China, making it less vulnerable to retaliation—something the company is familiar with. In 2015, China blacklisted Cisco, along with several other U.S. companies, from its government-approved purchase lists, after revelations by Edward Snowden that the U.S. National Security Agency had intercepted Cisco routers to install surveillance tools.

The catch for Cisco is that its diverse business—a quarter of its sales come from selling routers and switches to service providers—limits the impact from any share gains from Huawei. Nokia, Ericsson, Ciena, and Juniper are more exposed to the category. Leopold estimates that Nokia could see share gains worth about $740 million, or 2.5 to three percentage points of incremental sales growth.

THE NEUTRAL PARTY: TAIWAN SEMICONDUCTOR MANUFACTURING

If there is a Switzerland in this technology cold war, it is Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing(TSM), the world’s largest semiconductor manufacturer. The company’s knack for speedy innovation and ability to help companies modify their designs to improve their chips has made it a go-to manufacturer for a who’s who of technology, from U.S. companies such as Apple(AAPL) and Qualcomm to their Asian rivals like Huawei and MediaTek.

Taiwan Semi is roughly five times the size of its next closest rival, privately held GlobalFoundries, putting the company in a rare safe position in the tech cold war—and making it an attractive option for investors. “This is an asset that is critical for both the U.S. and China and not in the hands of either,” says Bhavtosh Vajpayee, an analyst on the $39 billion Oppenheimer Developing Markets fund, which owns Taiwan Semiconductor.

Taiwan itself is trying to maintain a similar neutral position. The island is to chips what Saudi Arabia is to oil. Taiwan accounts for about 60% of global capacity to make customized chips, like those used for AI or cameras in smartphones. But it’s impossible to ignore Taiwan’s precarious political position. Self-governed, it relies on the U.S. for military protection, but its economy relies on China—which considers it a province.

The natural question: Could China force Taiwan Semiconductor to cut off the U.S. or start a boycott? The company has been preparing for multiple crisis scenarios for years and has diversified its business to protect against things like a boycott, says Alberto Fassinotti, a portfolio manager for emerging market equities at global investment manager Rock Creek Group. Taiwan Semiconductor did not respond to a request for comment.

Analysts say any attempt by China to cut the U.S. off from accessing Taiwan and its chips would be challenged by the U.S., possibly turning a cold war into a hot one and upending all types of investment theses.

Taiwan Semi is a top holding for many global fund managers. The company’s strong balance sheet and 2.7% dividend yield offer investor protection, but those looking to buy may want to wait. Earnings estimates may still be too rosy, given the confluence of pressures facing the broader chip industry. Currently trading at 18 times forward earnings, the stock becomes more attractive below its historical average of 15 times, fund managers say.

CHINA’S INNOVATORS: THE BATS

Baidu(BIDU), Alibaba Group Holding(BABA), and Tencent Holdings(700.Hong Kong) dominate every aspect of the internet in China and drive much of the nation’s innovation. The companies have made aggressive pushes into digital payments, AI, and autonomous vehicles. But their reach extends well beyond China.

The companies have invested billions of dollars globally. Tencent is one of the world’s most active and aggressive tech investors, with stakes in Snap(SNAP), Activision Blizzard(ATVI), Tesla(TSLA), and Spotify Technology(SPOT).

Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent also are China’s ticket to becoming a more dominant technology player, which makes them attractive investments in the tech cold war. The BATs together also hold stakes in more than half of China’s 124 unicorns, (startups valued at more than $1 billion), according to a report by Deloitte.

“The Chinese government is very aware that if it wants to reach its goals, they need these companies to invest,” says Brian Bandsma, a manager on the Vontobel Emerging Markets strategy that oversees $15.7 billion and owns Tencent and Alibaba. “And companies helping China achieve its objectives will have more flexibility, allowing these companies to go into ancillary businesses with little competition and shielding investors from regulatory risk.”

The companies are still grappling with their own challenges—China’s economic slowdown is denting Alibaba’s sales, increased investment and marketing are pressuring Baidu’s margins, and regulations around gaming loom over Tencent’s stock. Those challenges are now reflected in the stocks. The three companies lost a total of $229 billion in market value last year, and each trades below its five-year price/earnings ratio. They may be China’s—and investors’—best hope for remaining part of the global tech landscape.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario