Recession: Are We There Yet?

By John Mauldin

An old joke says economists predicted 15 of the last 10 recessions. In other words, they’re frequently wrong and often too pessimistic.

I think it’s not so simple. Every recession prediction is eventually correct; some just get the timing wrong. That’s because, so long as we have a business cycle, a recession is always coming. The only question is when it will strike.

There’s also some dispute about what, exactly, counts as “recession.” The usual definition is two consecutive quarters of falling real GDP. But as I’ve written, GDP itself is a nebulous statistic with substantial margin of error. We can never be quite sure.

My own outlook has been consistent: The current growth phase is getting old and will end as they all do, but we probably have another year or so. That is about as far out as my data reads can actually give us any statistical confidence. Macro events like Federal Reserve error, trade war, ugly Brexit, and others could hasten the decline. But as of now, the US and the developed world seem likely to sustain at least mild growth through 2019.

That doesn’t mean we rest easy. It means we have time to prepare for the worse conditions that we know are coming. How much time? That will be today’s topic as we review some recent analysis.

Now let’s review the recession forecast.

Dramatic Weakening

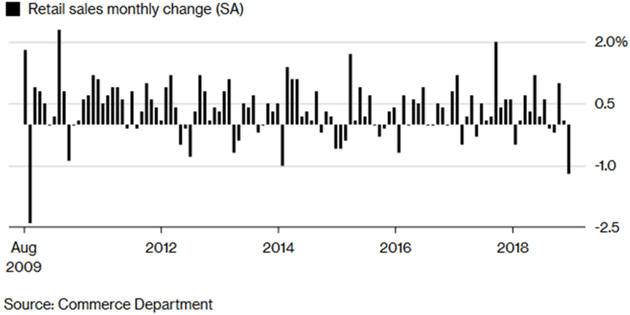

Recession antennae everywhere popped up on February 14 when the Commerce Department reported retail sales fell 1.2% in December. It was the worst month-over-month decline since 2009.

Now, there are reasons to doubt this report’s significance. It came out four weeks later than scheduled due to the government shutdown, and thus is more subject to revision than normal. It also conflicts with private-sector data like Redbook, which climbed sharply in December. And even if the data is right, this is only one month and one month doesn’t make a trend.

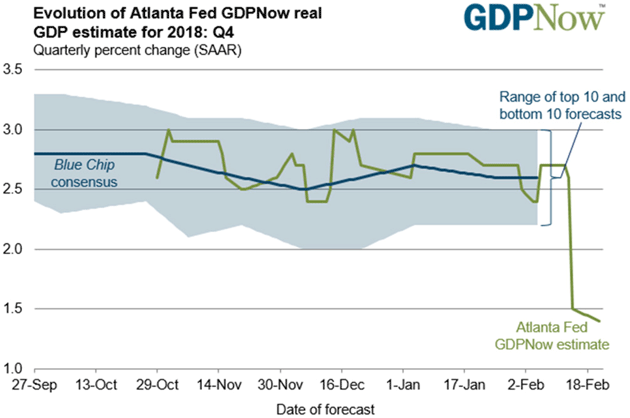

Nevertheless, retails sales are an important input to recession models like the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow. That model’s estimate for Q4 2018 instantly plunged from 2.7% just two weeks earlier to 1.5%. Ugh.

That will be a dramatic weakening if the final Q4 GDP report confirms it, but I doubt it will. I think this report is a glitch and will fade away as other data supersedes it. But even if it’s right, 1.5% GDP growth isn’t a recession. It would mean 2018 was an okay though not spectacular year, and a recession call by definition is at least six months away (since it takes two negative GDP quarters to mark one).

This illustrates an important point: The recession outlook is a moving target. It changes as we get new data. Forecasts should change with it, and I don’t blame anyone who lets new information change their mind. It might make me trust them even more.

I trust Dave Rosenberg of Gluskin Sheff—enough to make him a perpetual SIC speaker and he has been my “leadoff hitter” on the first morning for at least 10 years—but at the moment we disagree.

Dave is screaming recession every chance he gets, which for him is every business day in his Breakfast with Dave letters. But he is not a perma-bear by any means. He’s been bullish at the right times in the past, so I pay attention even if I’m not convinced. I should note he turned uber-bullish nine or 10 years ago, announcing his new forecast at my conference. It was way outside the consensus at the time, but Dave has never cared much about being part of the consensus.

Dave summarized his argument in a letter last month (Over My Shoulder members can read it here), weeks before the retail sales report knocked the legs out of more bullish outlooks. If that data holds up, he’s going to look more prescient than most.

His key points make a great launching pad for discussion about the probabilities of recession. This letter will be more like a back-and-forth between Rosie and I when we are together. I hope you enjoy our conversation. My comments are in brackets. His points are in italics.

His key points:

- We are now in month #115 of the current expansion, double the post-WW2 norm and five months from becoming the longest ever.

[I guess I just shrug my shoulders and ask, “so what?” We have maybe a dozen data points of recoveries after recession. Maybe when we have 100 we can start talking about statistical probability. There is no statistical reason this recovery couldn’t last a lot longer. Ask Australia. Maybe 10 cycles from now we’ll have another lengthy recovery and start talking about this period as the longest recovery ever.]

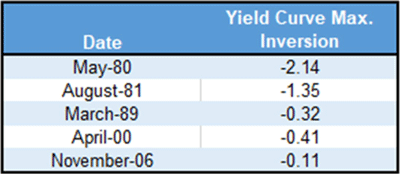

- The yield curve doesn’t have to completely invert for a recession call. It barely did so the last two times.

[Agreed. This table from Michael Lebowitz at Real Investment Advice measures the size of the last five 2Y/10Y yield curve inversions. You see they’ve been getting progressively smaller. If that trend were to continue, we might not even need a yield curve inversion to signal recession.

Much of the curve is already inverted at the short end. Here are the rates from last Tuesday.

- 1-month: 2.41%

- 3-month: 2.45%

- 6-month: 2.51%

- 1-year: 2.54%

- 2-year: 2.50%

- 3-year: 2.47%

- 5-year: 2.47%

- 7-year: 2.55%

- 10-year: 2.65%

Notice the one-year to five-year is inverted by seven basis points. Likewise, the seven-year is only one basis point away from inverting against the one-year note. The short end of the curve is unusually flat and some points are inverted.

About five years ago, maybe more, I was at speaking at a conference where David Rosenberg and David Zervos (of Jefferies) were on a panel aggressively arguing that the yield curve would have to actually invert before another recession. Remember, this was when the Federal Reserve was holding rates at zero, seemingly forever. I aggressively questioned them later as to how the yield curve could invert? I maintained that we could have a recession without a full inversion. They both thought that eventually the Fed would raise rates, the yield curve would invert, and we would have a recession.

Times change and the facts change, too. But I think David is right now. We don’t have to have a full 2Y/10Y inversion to signal a recession. It may happen, but then again that inversion is typically a year in advance.]

- Stocks appear to have peaked last fall. Average lead time from market peak to business cycle peak is seven months.

[Maybe. Then again, a solution to the China trade war and a solution to Brexit coming at roughly the same time could cause a market melt-up and new highs. On the other hand, Doug Kass thinks the market is getting ready to roll over and is increasing his short exposure.]

- Fed policy changes are coming too late. It already overtightened, as it did so often in the past. Rosenberg thinks “neutral” Fed Funds rate is no more than 1.75%, so the last two hikes were missteps.

[Again, maybe. I agree the neutral rate is historically low but it may be somewhere close to where we are today. This is something we will only know for sure in hindsight. If 50 basis points is the difference between slow growth and recession, then this economy is extraordinarily weak and is likely to enter recession anyway.]

- Recessions historically begin when the unemployment rate climbs 0.4 percentage points above its cycle low, which this time seems to have been 3.7%. So 4.1% unemployment, when it happens, should ring an alarm bell.

[Completely agree. I’ve actually used charts in the past connecting small increases in unemployment with the onset of recessions.]

- The recession will probably be mild but there is no correlation between a recession’s severity and how far equity markets decline. [Agreed.]

- This time, the bubble is on corporate balance sheets as firms borrowed money at historically low rates. Instead of productive use, much of the borrowing went to share buybacks. This did nothing to cover future debt-servicing costs.

[This is something I’ve been writing about at length. I think corporate and high-yield debt and leveraged loans will end up being the next recession’s subprime mortgage loans, triggering a liquidity crisis which could be quite severe.]

- While many focus on high yield, the leveraged loan market is in a bubble of its own. A key risk for this year is a debt refinancing “tsunami” as trillions in debt has to be rolled over at higher rates.

[No argument here. That “tsunami” could actually cause a recession.]

- Share buybacks and capital spending will be curtailed as cash flow falls while wages and debt servicing costs rise.

- A 35% decline in stocks would be typical for this kind of recession, though Rosenberg thinks some non-cyclical and defensive names could outperform.

To zero in further, I think the main question is whether the Fed stayed hawkish too long, as Dave thinks, or is loosening up in time to keep the economy growing. We don’t know yet. For that matter, we don’t know if they are turning dovish. We only know they’re talking about ending the rate hikes and/or ending the balance sheet reductions. The FOMC meets again March 19–20 so whatever they do then should tell us more. And if the economy perks up? The Fed can talk about more tightening later in the year.

No Credit Stress

Canaccord Genuity analysts Tony Dwyer and Michael Welch differ from Rosenberg, and outlined their own case in a February 13 Macro strategy note titled “Still no recession in sight.”

Dwyer and Welch concede all the big question marks: slowing growth, Brexit, trade war, and so on. Their conclusion is these will make the Fed even more dovish than it would otherwise have been. They think the Fed can do this because four factors will forestall recession. Quoting from their note:

- NFIB Small Biz Optimism Index cycle peaks offer long runway. Clearly, survey-based indicators have seen sharp declines from their respective August 2018 peak, which makes sense given the Q4/18 market crash and early-year US government shutdown. The good news is the cycle peak in the NFIB Small Business Optimism Indices historically leads recession by a median 41 months. It is even longer if you use the last three credit-driven cycles.

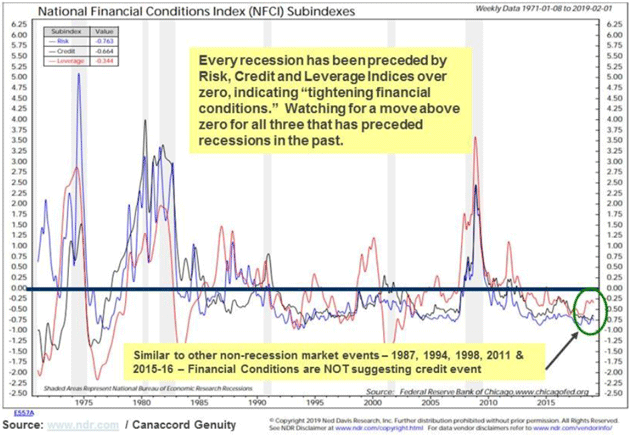

- Credit Stress Indicators never even budged as market swooned. It is hard to have a credit crisis when there aren’t any signs of credit stress. Again, we turn to the Chicago Fed’s National Financial Conditions Subindices that measure 105 indicators of credit stress in banking, shadow banking, and the financial markets. These subindices barely moved, suggesting a fear-based market event rather than a sign of a coming credit crisis-driven recession (Figure 3).

Source: Canaccord Genuity

If Rosie is right and the Fed has already tightened too much, we should see it in credit conditions. We don’t, at least not yet. Credit is still available to businesses that need it, although at higher rates in some cases. That’s not all bad; it might mean fewer “zombie” companies haunting the economy. The question is whether their demise will cause other damage. We shall see.

Not Going Global

So far we’ve talked about the US economy, but no country is an island anymore. All are exposed, more or less, to the greater world economy. So let’s look overseas.

In Italy the recession argument is over because they are officially in one. That got lost in other news but it really is happening. The Italian economy shrank 0.2% in the fourth quarter, following -0.1% growth in Q3. That is about as mild as a recession can be, but it counts. Germany may not be far behind. Europe’s largest economy contracted -0.2% in last year’s third quarter. Reports suggest the fourth quarter was no better and possibly worse.

Meanwhile in Asia, China is not in recession and nowhere near one, if we believe government data. Much depends on how (or if) the country resolves trade disputes with the US. As of now, a comprehensive agreement still looks elusive but Trump appears willing to extend the March 1 deadline for another tariff hike. The uncertainty isn’t good, but it’s better than a major trade war.

Looking internally at China, we all want to know how long Beijing can sustain such amazing growth rates. Gavekal’s Chen Long wrote in a report this week that China’s credit cycle appears to be turning back up after a few rough months. He sees solid bank lending and a recovery in the “shadow” banking sector contributing to overall credit growth. This typically leads economic growth by 6–9 months, suggesting the Chinese economy could be back on firmer ground by this fall.

Again, all this is subject to macro risks. All bets are off if China weakens too much or the UK makes a hard Brexit. As of now, however, nothing is exploding in a way that would set off a worldwide recession. That suggests 2019 may not be a great year in the markets, but it won’t be a terrible year, either. Things could certainly be worse.

Shane and I fly to Dallas tomorrow to begin moving our furniture to either Puerto Rico or a new, smaller apartment that will be our Texas base. The sale of my other apartment should close next Friday.

Monday night I will be in Athens, Texas for an Ashford, Inc. board meeting, then Wednesday morning I fly to Houston to meet with SMH and then on Thursday with the RISE economic council at Rice University. Then back to Dallas to help Shane move us and back on a plane the next day to return to Puerto Rico.

I’m going to hit the send button as thinking about Pat Caddell doesn’t have me in the mood to tell any personal stories. So let me wish you a great week, as we all need to spend more time with our friends and family, appreciating what we have.

Your going to miss Pat Caddell analyst,

John Mauldin

Chairman, Mauldin Economics |

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario