Sell Stocks Before The Corporate Debt Bubble Bursts

by: Global Opportunities Analys

Summary

- Corporations have piled on record amounts of debt to buy stocks.

- Recently their investment in stocks has turned sour while their debt burden has just started feeling heavier.

- Corporate executives will likely cut back on share purchases, and this in itself is bad news for the future.

- Add to the above the fact that the economy is slowing and executives expect recession, and stock investors become even rarer.

- Recently their investment in stocks has turned sour while their debt burden has just started feeling heavier.

- Corporate executives will likely cut back on share purchases, and this in itself is bad news for the future.

- Add to the above the fact that the economy is slowing and executives expect recession, and stock investors become even rarer.

It was just on December 15th when I argued that the S&P 500 was "likely to crash deep below 2.600", and a few days ago that I wrote that it was a good time to buy stocks as the S&P 500 was around 2.400. My buy recommendation was for a relatively short period of time. The market has since bounced back nicely. Things have been moving dramatically, and the US stock market of the past couple of weeks has behaved nothing short of extraordinary. You don't see such movements every year, and there have been many decades without such sudden market crashes in the US. These times have also been great opportunities for making good profits from short-term trading, though obviously extremely few people are able, or willing, to enter such trades involving gut wrenching volatility.

Now that the market has recovered quite a bit I believe it is time to start looking at the truly bad fundamentals and position for the coming year. And I believe, as I also mentioned in my last article, that 2019 will be a bad year for risk assets, particularly for stocks. It is not very wise to stay invested until the economy starts showing significant signs of weakness. But early signs of weakness are already there, as housing, and the economy in general, have started to lose steam in recent months.

These weaknesses are likely to get worse as the economic cycle moves along its already historically long lifespan. There are some serious concerns out there, which actually led to the crash we had from October to December. Let's start from perhaps the most immediate and important concern - the corporate debt bubble. Most people talk about the trade war with China, or the Fed rate hikes, but the fact is that a strong economy can withstand such challenges. The real risk, and the real fear of the market, is growth, or the lack of it.

What led to the financial crisis of 2008? Most would agree that, ultimately, it was about easy money. Easy money pushed capital toward wasteful investments which eventually popped and caused a massive crash. The major wasteful investment that popped back in 2008 was real estate. What happened after 2008? As everybody knows, money got even cheaper. Central banks in the whole world cut interest rates and took other monetary measures (such as QE) in order to tackle the dire economic consequences of the crash of 2008. Central bank rates are currently, still, below zero in Europe and Japan.

With hindsight, we know what was the major wasteful investment before 2008. What few agree upon though is about the wasteful investments afterwards. Very few before 2008 thought that investing in real estate could ever blow up in their faces, let alone cause a global financial meltdown. Since many economists and politicians thought that it was improper banking regulation that led to the 2008 crash - rather than too low interest rates - they believe that we are going to be just fine this time around because there have been significant changes, and improvements, to banking regulations. And they believe this will prevent another financial crisis, or at least one as bad as 2008. It is indeed unlikely we will get exactly the same kind of crisis we had last time, but cheap money has, again, and on a much larger scale, pushed capital into risky, speculative, and wasteful investments. And wasteful investments always blow up, sooner or later. I believe that wasteful investments have been aplenty in the years since the financial crisis of 2008. One popular case is China, where zombie corporations, and ghost towns, have been spreading in recent years. Of course there are too many areas of wasteful investments, all around the world (not just in China), and even real estate is not far from what it used to be before the 2008 crash. Many real estate markets are again overvalued and there is a lot of building going on which can, again, go bad. But I'm going to focus more on the US corporate debt problem, which it seems, is in a more immediate danger than other bubbly areas of the world economy. And since money has been much cheaper, for longer, I don't see why a potential future crisis would not be much bigger, and a lot more complicated (perhaps even impossible) to contain than the crisis we had a decade ago. Let's not forget that the world's central banks no longer can cut interest rates by 500 basis points (5%) as the Fed did last time (or in earlier recessions), which led to a rather quick recovery in asset prices. The absence of this monetary tool is probably the greatest of worries economists, and investors alike, should think about.

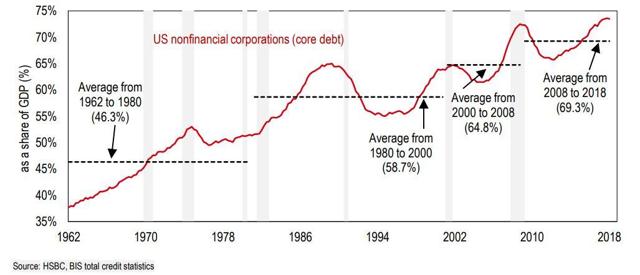

What first comes to my mind about the consequences of cheap money, which could blow up much sooner than many think, is the corporate debt bubble in the US. US corporations are carrying more than $9 trillion in debt. The share of non-financial corporate debt to GDP is at record levels, higher than its inflated levels during the 2008 financial crisis (chart below).

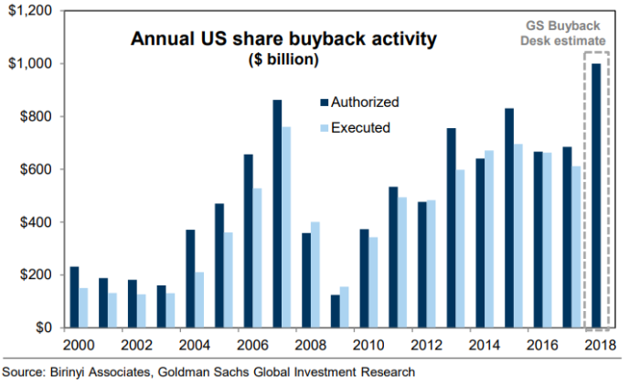

But the most important issue is not the size of the US corporate debt, but what most of that debt has gone to, which is alarming. This year alone US corporations are supposed to have spent $1 trillion in share buybacks (chart below).

Corporations have massively borrowed money to buy back their own shares. Why have they done so on such a scale? They thought interest rates are not going to stay low for too long, and that the low interest rate environment is a rare and extraordinary occasion they have to take advantage of. The belief that inflation, and interest rates, were going to rise over the coming years was almost unanimous up until a month ago. However I argued back in June that longer duration interest rates would likely go lower. My belief was almost seen as equal to madness.

Up until a month ago it seemed like there was competition among economists, business executives and investors, on who would predict higher interest rates for the coming quarters, or perhaps couple of years. Back in August one of the most respected US executives, JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon, not content with his previous prediction of 4% longer-term interest rates, went even further and predicted a 5% yield for the US 10-year treasury. Such beliefs offered motivation to borrow as much as possible, as early as possible. Interest rates did go up for a while this year - as bearish bets against long-term US treasuries reached record levels - but they have been falling quite sharply in recent weeks. US corporations piled on debt to buy back their shares and those trillions of dollars pushed their stock prices to record levels. What happens now that some corporate executives are beginning to see a major flaw in what they believed - that interest rates aren't exactly going up? Does all that debt used for buying shares get riskier, and cheaper, than it used to be? Corporate bonds have already started feeling the heat.

What happens if it is not only the interest rates not going up, but also stock prices going down because the Fed just raised its benchmark rates again while the economy softened? And this is what just happened for the past couple of weeks. Corporations have used longer duration debt, bearing interest ranging usually between 3 to 6 percent, to buy back their own shares (or other companies' shares in mergers and acquisitions) in the belief that higher inflation will take care of most of their debt burden. If inflation is low (and interest rates are also very low, historically), and you get a 10-year loan with fixed (low) interest, and then inflation rises, this makes your loan a nice deal as inflation erodes your debt and makes repayment much easier.

This is what most companies binging on debt were thinking of. They are now starting to fear they may have been wrong. However the fear is not really strong yet, and it has a lot more room to spread and become rather mainstream.

Corporate executives didn't believe inflation could stall, or perhaps fall in the following years.

As US longer duration treasury yields show, bond investors believe that inflation is not going to rise any time soon. The 10-year US treasury is yielding around 2.7%, which is just slightly higher than the Fed overnight rate of 2.5%. And the data are showing that inflation is not rising above the 2% target of the Fed but it is rather showing signs of slowing.

The recent stock market selloff was a warning sign, first of all, for all the companies which have piled on debt to buy shares. I think the market has started to scare them, and they will most likely cut back on share purchases on borrowed money. This action alone can cause further weakness in the stock market. If you spend trillions of dollars in buying back your own shares, and you see the stock price crash - as they just did - it makes you think more carefully about future buybacks. This is beside the fact that a slowing economy, without higher inflation, is making their debt-laden balance sheets more vulnerable. Not many executives are panicking yet, but they might start soon. After all, the market is still a lot higher than it was just a couple of years ago, and this often justifies some smart panicking. It is also reasonable to expect not so many share buybacks next year based on the serious pessimism permeating US executive scene for 2019 and 2020. According to a study recently published, 80% of American CFOs believe recession will hit by 2020 (and almost half expect recession by 2019). Why would they, rationally, invest in share buybacks now?

Nevertheless so far not many are fretting about the dangers that all the trillions spent on share purchases, either in buybacks or in mergers and acquisitions, can pose to corporate balance sheets in an unfriendly market environment and how it can cause panic and a serious crisis, in sectors we can consider completely unrelated. After all, the 2008 crisis started from real estate and spread to all corners of the economy, and to all the trading partners of the US, which had nothing to do with real estate speculation. This is why I believe it is a good idea now to sell and just stay opportunistic. A corporate debt panic in the US can cause a lot of damage and it would not be contained easily. The crash of 1929 was mostly caused by stock market speculation on margin - meaning borrowed money.

It is true that we do not have exactly the same situation now, as companies are not involved in short-term speculation of share prices. Nonetheless, fundamentally speaking, it is still called stock market speculation on borrowed money, though the time horizon of the speculators is longer now than it was in the late 1920s. Corporate executives have been speculating on their share prices, and they have been doing so with borrowed money. Corporation will not be forced to dump the shares they have bought, as retail speculators did back in 1929 after margin calls, but corporations can face serious difficulty with their record debt levels. Corporate 'margin calls' can occur when their bonds get dumped and they can no longer refinance. Corporations may soon face the reality of having squandered trillions of dollars on share prices which have crashed. In case inflation goes much lower, and US treasury yields fall further, corporate debt repayment will become impossible for many companies. And this thought has just turned into a real possibility with the recent stock market crash associated with a sharp fall in US treasuries (chart below).

Maybe the market goes up a little bit more, or maybe it stays around current levels for a while.

But the future, especially next year, looks very risky, and not worth investing in risk assets, especially when you can still buy US treasuries which yield more than 2.5% and carry no risk.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario