Nervous, cost-conscious investors aren’t making it easy for fund managers to grow profits

By Paul J. Davies

It was a rough year for listed asset managers in 2018 and things likely won’t get easier this year. Deals to build scale may be investors’ best hope.

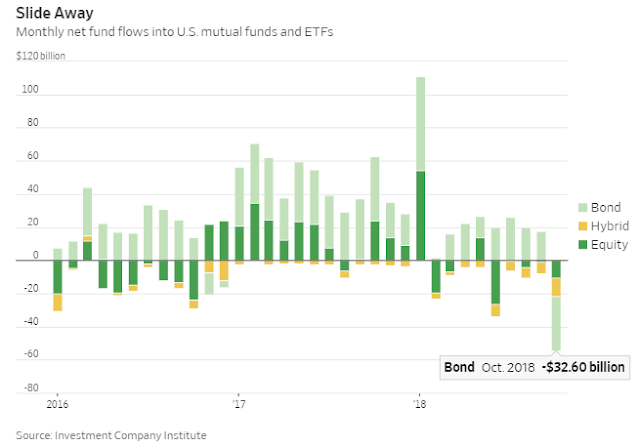

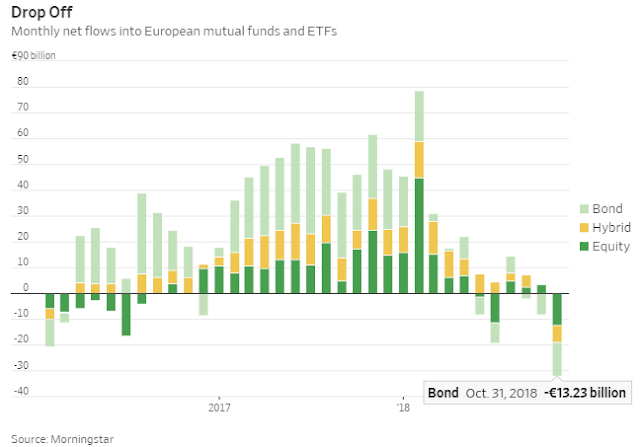

As stock and bond markets wobbled in 2018, the shares of listed fund managers performed far worse. That’s even before their clients started redeeming money in greater numbers in the third quarter.

The simplest explanation is that investors haven’t faced such uncertainty about the direction of global growth and geopolitics arguably since 2008. That has hit asset prices and hence the profits of asset managers. But there are also business pressures; above all, the competition for assets and fees brought by the rise of index investing.

Those suffering most are old-fashioned active managers, comprising the industry’s squeezed middle. On one side, cheap index managers are winning investors’ funds with good-enough performance. On the other, expensive alternative managers claim much higher returns from being properly active owners of often illiquid investments.

Traditional managers are both losing assets and being forced to cut fees—a double hit to revenues. Active managers’ share of global industry revenues shrank to 41% by the end of 2017, from 64% in 2003, according to the Boston Consulting Group, while their share of assets under management shrank to 52% from 76%. The consulting firm forecasts a revenue share of just 36% and asset share of 45% by 2022.

Regulatory changes are also piling pressure on costs and profitability. Both in the U.S. and Europe, reforms have forced more transparency on financial-services fees, which often come back to how savings products like funds are sold.

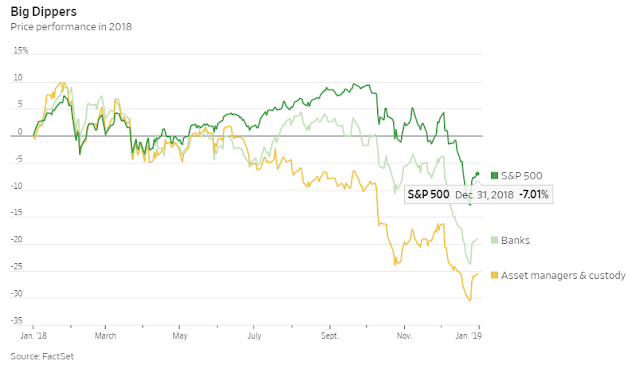

The shares of U.S. fund managers have done worse than those of banks. While the S&P 500 was down 7% in 2018, banks in the index dropped nearly 20% and asset managers more than 25%.

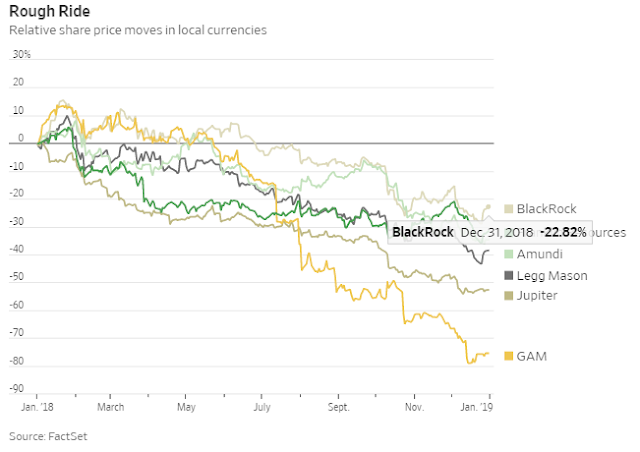

Even a monster asset-gatherer like BlackRock was down 23%, although Franklin Resources and Legg Mason both did worse, falling 35% and 38% respectively.

In Europe, GAM of Switzerland fell 76% after a profits warning relating to an acquisition and a scandal at its bond funds that led to the suspension of one manager. Several rivals’ shares lost between 30% and 50% even without such tribulations.

One likely consequence of this industry shakeout is more deals that boost scale and produce administrative cost savings, such as Invesco’s recent purchase of OppenheimerFunds from MassMutual, the U.S. insurer.

Banks in the S&P 500 dropped nearly 20% last year and asset managers more than 25%. Even a monster asset-gatherer like BlackRock was down 23%. Photo: Rudnik,Christian/Zuma Press

Fund deals have a mixed track record. Active managers often rely on individuals for their performance or their reputation, and takeovers can lead to bust-ups or overlapping roles, prompting managers to leave and clients to leave with them. Deals tend to work better when the acquiring company lets those it acquired retain independence, as Pittsburgh-based Federated Investorsis doing with Hermes in the U.K., or when the target is more technology-oriented, as was the case in BlackRock’s 2009 deal for iShares, the ETF manager.

Premiums for potential takeovers aren’t yet reflected in the share prices of smaller listed managers that would make natural targets, according to UBS analysts. Bid interest could be the only thing that boosts asset management’s squeezed middle in 2019.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario