Buttonwood

For Europe’s stockmarkets to recover, bank shares need to rally

Investor sentiment has curdled from indifference into something closer to hatred

.

NOT SO LONG ago, a stockbroker trying to interest an American fund manager in European shares would be met with an eye-roll. But sentiment is fickle and attitudes change. These days the likely response is a hard stare. Over the years in which stockmarket returns in America pulled ahead of everywhere else, any residual feelings for old-world shares had slowly turned to indifference and then curdled into something like hatred.

For what is there to like? The Euro Stoxx 50 index of euro-zone shares is lower than it was 20 years ago. Earnings forecasts have been steadily cut this year. Political risk—from Brexit to Italy’s budget stand-off with the European Union—is never far away and, seemingly, never resolved. “Call me when it’s over,” is the refrain of many American investors. Do not get them started on Europe’s structural defects: its ageing populations, scarcity of world-class digital firms and fragmented markets.

The category of stocks that captures the prevailing euro-misery best is banks. They have everything that makes investing in Europe such a wretched experience. In a dispiriting year for European markets, the shares of banks and financial firms have been among the worst-performing. Even after the selling, they are a fifth of the MSCI pan-European index. The gloom is now so deep that it would take just a few rays of sunshine to give bank shares a lift.

For now, though, the news is relentlessly bad. GDP in the euro area grew at just 0.2% in the third quarter. The purchasing managers’ index of activity fell in October to a two-year low. Exports have wilted, notably to emerging markets, where firms listed in Europe earn a third of their profits. A weak economy defers the day when Europe’s central banks can tighten monetary policy. The delay hurts banks, whose profits depend on the interest rates they charge on loans.

Europe’s cyclical failings are entwined with a host of other flaws. Its people are ageing and its businesses seem outmoded. It is not just the preponderance of banks. Stockmarket indices are loaded with makers of cars, chemicals and capital goods—the machine technology of the early 20th century, not the digital tech of the 21st.

Nor is Europe a truly continental market in the way that America is. Banking is essentially national. Its capital markets are puny. And it lacks a single set of fiscal-policy tools to go with its single currency. The euro area has no shared deposit protection or unemployment insurance. There are more signs of Europe pulling apart than of it pulling together. One big country, Britain, is going through a messy divorce from the EU. Another, Italy, is feuding with the EU over fiscal rules. The larger these political risks loom, the harder bank shares fall.

Is there anything positive to say about them? European banks are a leveraged play on Europe and also on the global economy, says Luca Paolini of Pictet, a Swiss wealth-management group.

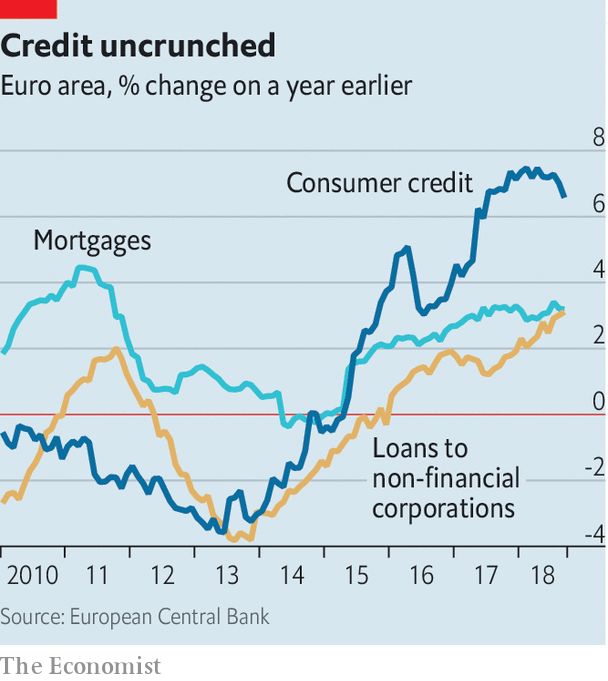

That cuts both ways. They are hurt badly by bad news; but they can also rally hard on good news. The starting-point is that shares are cheap—banks are priced for something like a calamity. Yet after foot-dragging for a decade on bad loans and capital-raising, their balance-sheets are in decent shape. Bank credit in the euro zone is growing again (see chart).

A lot of Europe’s political fog would have to clear before its banks could deliver more than a short-term bounce. A softish Brexit would help, of course. So would a truce over Italy’s budget. The euro zone’s structural weaknesses are not going to be fixed quickly. But there has been more progress than is generally recognised.

France and Germany recently agreed on a proposal for a European budget. It falls well short of the kind the recession-fighting fund requires. But once it is in place, it might grow in size and flexibility—just as the makeshift rescue of Greece in 2010 evolved into lasting backstops for troubled countries, such as the European Stability Mechanism, a €410bn ($470bn) bail-out fund. The chance that policymakers move towards fiscal integration in this way is around 30%, according to strategists at Morgan Stanley. This would benefit financial stocks most, they reckon.

There is one other thing, perhaps a little strange, to say in favour of European stocks, particularly banks: that few investors have anything favourable to say about them. They are a contrarian bet—the antithesis of American tech stocks, which are suddenly out of favour. You buy them when everyone else has given up on them. Isn’t that right now?

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario