Emerging Markets Roundtable: Today’s Pain Could Be Tomorrow’s Gain

By Reshma Kapadia

Eddie Guy

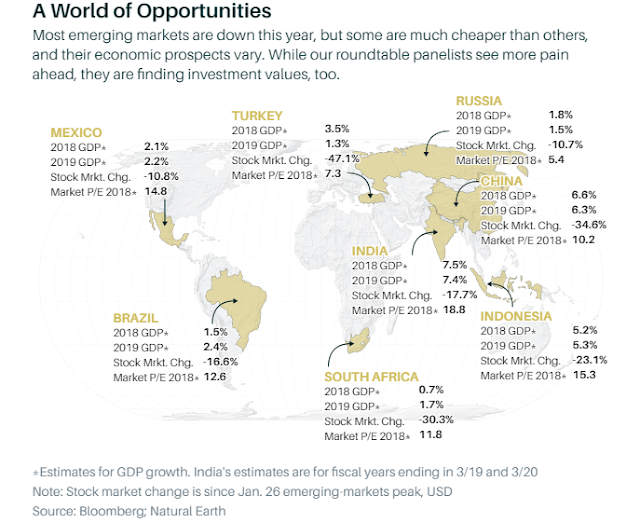

Emerging markets have had a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad year. In other words, the stocks have sold off sharply, and the currencies have been hammered as U.S. interest rates rise and China’s growth slows. The benchmark MSCI Emerging Markets index is 23% below its January high, after rising 34% last year. China’s Shanghai Composite index has fallen 35%. Turkey’s lira has lost 37%, and the pain could spread.

Yet, the latest washout obscures the long-term attraction of these markets: Not only does 83% of the world’s population live in emerging markets, but almost half of this population is middle-class, and new industries catering to these hungry consumers are creating just the sort of change and growth investors crave. With emerging-market stocks trading at steep discounts to U.S. equities, now is the time to start bargain hunting, or at least drawing up a shopping list.

To assist in both efforts and assess the broader outlook, Barron’s recently assembled a roundtable composed of four investors active in global markets since the late 1990s, when emerging markets had one of their most painful crises. Our panelists are Ruchir Sharma, head of emerging markets and chief global strategist at Morgan Stanley Investment Management; Justin Leverenz, manager of the $35 billion Oppenheimer Developing Markets fund (ticker: ODMAX), the largest actively managed equity fund in the category; Richard Sneller, co-manager of the $1.9 billion Baillie Gifford Emerging Markets Growthfund (BGEHX), which has outperformed 96% of its peers over the past three years; and Laura Geritz, who built a strong investment record at Wasatch Advisors investing in frontier and smaller markets, and launched Rondure Global Advisors in 2016. Geritz runs the firm and also manages the Rondure New World(RNWOX) fund, with about $120 million of assets.

While this erudite foursome thinks the recent selloff isn’t over, panelists note that many developing countries are in better shape than investors have assumed. Even China, which reported third-quarter economic growth of 6.5% on Friday, the weakest rate in nearly a decade, still has plenty of gas in the tank.

Barron’s: What is ailing emerging markets this year?

Ruchir Sharma: Emerging markets have been working out the excesses after a decade of breakneck growth—whether it’s fiscal excesses in Brazil, monetary excesses in places like Turkey, or debt excesses in China. The workout has been going on for five or six years, but got everyone’s attention this year because of the strength of the U.S. dollar and rising U.S. interest rates.

Justin Leverenz: Rising rates bring capital back into the U.S. That puts vulnerable countries, such as Turkey, in an especially bad position. Its economy has grown by 3.5 times in local currency since the financial crisis, largely because of an increasing dependence on credit borrowed from foreign investors. Other factors include China’s slowing economy and idiosyncratic circumstances such as Brazil’s presidential election [the second round of voting occurs on Oct. 28] and questions about whether the victor will push through needed [pension and other] reforms. Then there’s the rise in oil prices, which hurts countries without oil production, such as India, Turkey, and Indonesia.

Laura Geritz: The slowdown in China started the panic this year, and rising U.S. rates compounded it. Complacency about the dollar’s value caused other countries to take balance-sheet risk, issuing dollar-denominated debt. There is just too much debt.

Richard Sneller: For some perspective, about 24 months ago, emerging markets were at levels about 15% lower than today’s.

Are they returning to those lows, or rebounding?

Leverenz: Emerging market equities look reasonably good. That doesn’t mean they wouldn’t go along with a big pullback in the U.S. or developed markets, but I don’t see current problems causing contagion. Most countries have flexible currencies, and fiscal balances aren’t a big problem. If problems worsen, the impact would be manifested in emerging market bonds, which skew heavily toward Eastern Europe, Africa, and Latin America. Asia accounts for 70% of equity managers’ investments.

Geritz: Valuations were down to 10-year average multiples [of earnings] in early October. Investors have been pulling their money from frontier and smaller emerging market countries. Higher-quality stocks have finally started taking a hit, which is what I want to see before getting excited. The selloff might have a bit more to go before stocks bottom.

Sharma: The valuation gap between the U.S. and the rest of the world hasn’t been this wide since the late 1990s. Valuations are telling you that emerging markets are the place to be for the next five to seven year. The question is whether there is one more leg down. China is the only thing big enough to cause that—and the one thing I worry about.

Richard Sneller Philip Vukelich

What worries you most about China?

Sharma: No country in history has taken on as much debt as China did over the past decade. We’ve been told it’s OK because it is internally owned and the Chinese can keep managing it. But this is the first time that U.S. and Chinese interest rates have converged. In the past, whenever China had a slowdown, it could offset it by levering up some part of the economy to stimulate growth. As interest rates rise in the U.S., China can no longer ease monetary policy without the risk that people take their money out of the country—even with capital controls.

Leverenz: I’m not concerned about China. Growth will slip due to external challenges, slower credit growth, and the country’s focus on deleveraging, as well as more cautiousness about local government spending. But the economy can grow sustainably at 5%, compounded, for the next five years. That is still 30% to 40% of worldwide growth, making China the single biggest engine of growth behind the U.S. China has rebalanced its economy away from exports toward domestic consumption in a remarkable way that doesn’t get coverage. A decade ago, China had an enormous current account surplus, which has evaporated.

Has the market adjusted to a 5% growth rate? That is well below levels of the past 10 years, and below this year’s estimated 6.6%.

Leverenz: I don’t know. The Hang Seng index is down 15% this year, and China’s A shares are down 28%. Debt isn’t an enormous problem. The fundamental problem for China is that it saves too much. China also has fiscal capacity like no other nation on Earth—a low fiscal deficit relative to GDP, and huge reserves of assets to bail out banks. if needed.

Sharma: But over the past decade, debt has increased massively, and the savings rate is the same as in 2008. What can justify that? That is my issue.

Laura Geritz. Philip Vukelich

China recently reduced the amount of reserves banks need to hold, and gave exporters larger rebates. Is that stimulus a concern for investors?

Leverenz: Any stimulus will proceed in dribs and drabs, but the credit taps are unlikely to be opened wide since that would go against the country’s need to rebalance its economy and clean up its financial sector. Without the ability to launch big stimulus packages as in the past, China might implement reforms focused on redistribution of the economy, targeting the hundreds of millions of people living in urban areas who don’t have access to health care and education.

Sharma: Data suggest a slowdown is under way, and the extent of it may be more than what is widely believed. Most emerging markets in this circumstance would be raising rates. But if China is really concerned that the trade war is hurting its growth engine, it might lean toward more stimulus. That’s the risk for the next year because it would increase the risk of capital flight.

What is the best way for investors to navigate China and other emerging markets now?

Geritz: We see a lot of emerging market companies with net cash on their balance sheets. That’s different from the past. Take Yum China Holdings [YUMC]. At Yum! Brands[YUM], the U.S. company, net debt is about three times Ebitda [earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization]. Yum China has net cash. There is a lot of potential for it to borrow and follow the U.S. business’ route to prosperity: Issue debt and buy back shares. And the stock is cheap.

Sneller: The average price/earnings ratio of our top 10 stocks is slightly below that of the past decade. They are cheap because growth is improving for many of these companies, including China’s Ping An Insurance Group [2318.Hong Kong], India’s HDFC Bank[HDB], and Samsung Electronics[005930.Korea].

Sharma: Outside of the megacap technology stocks and the biggest countries, everything has been pulverized and neglected. Many of these companies have good growth prospects. China, Korea, and Taiwan make up about 60% of the emerging markets index, while countries such as Poland, the Philippines, and Turkey account for about 1% each. I’m willing to bet that isn’t going to be the case in five or 10 years, so my best idea is to sell megacaps and buy everything else in terms of smaller countries and smaller companies. There’s an opportunity in companies in Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe, for example.

Geritz: I agree. For the past year, the smaller the size, the worse the performance. Fundamentals have been fine for a lot of small-caps, yet companies such as Aramex [ARMX.UAE], the FedEx of the Middle East, and Philippine Seven[SEVN.Philippines], which runs 7-Elevens, have been left in the dust as investors in small-cap and frontier markets sell what has done better to meet redemptions.

Justin Leverenz Philip Vukelich

How does the current trade conflict affect emerging markets?

Sneller: In the 20th century, the competition was between Europe and the U.S. In the 1950s and 1960s, the battle was around space between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. Now China has arrived on the scene. It’s not about trade. The core issue, as Russian President Vladimir Putin said, is that he who wins artificial intelligence, wins the world. Protecting intellectual property lies at the heart of what is going on.

Leverenz: About 20% to 30% of the incoming undergraduates at top U.S. schools are Chinese, as are about half those in U.S. graduate schools in life sciences, physics, and math. China has the world’s most significant pool of intellectual talent; it has a lot of capital and a lot of data—whether in ride-sharing with DiDi, commercial data with Alibaba Group Holding[BABA], or transactional data with Alibaba’s Alipay. Data is the fundamental ingredient in artificial intelligence and algorithms. China is going to be a formidable competitor, and there are some wonderful opportunities to invest in, including Alibaba, arguably one of the most audacious companies on the planet. But the U.S. can’t permit the rise of China as an equal, and Beijing doesn’t have the domestic political capacity to make significant concessions, so this tension is going to be a permanent state of affairs.

Geritz: Among the Asian countries, Vietnam has the highest dependence on exports. Everyone there cites China as their biggest risk. If China’s currency weakens, Vietnam will devalue its currency to make its exports more competitive. But over the long run, manufacturers will want to diversify their production to Vietnam to minimize the trade risk. That’s one reason why I’m bullish on Vietnam.

Sharma: An era of de-globalization is a challenge for emerging markets because their mantra for success has always been to export their way to prosperity. Vietnam is a classic example. But it is going to be much more difficult because borders won’t be as open for goods and services, capital, or migration. Even in technology, we are seeing walls come up around countries.

Let’s switch to India, where the economy has struggled in recent years. Is it poised to recover?

Geritz: On the ground, things feel like they are picking up after two weak monsoon seasons, a tax overhaul, and de-monetization hurt growth. But the stock market has had a big run as investors have left China and shifted to India because its domestically oriented economy makes it less vulnerable to trade tensions and its debt to gross domestic product is low. Also, there are a lot of skeletal-looking buildings on Mumbai’s skyline—the kind you saw during the Asian financial crisis that began in 1997 in Indonesia and Thailand when funding dried up. There might be some problems ahead.

Sharma: We are all conditioned to think about how markets reflect economic fundamentals, but it can be the other way, and that is what we are seeing in India. Everyone had been excited about the economy recovering, but now the situation is changing because of financial developments that have taken place as rates rise in the U.S.

Ruchir Sharma Philip Vukelich

Are you referring to the pressure on the rupee, which caused India’s central bank to raise rates?

Sharma: That’s the concern. We are seeing some signs [of stress] emerging.

Sneller: People haven’t fully appreciated two significant transformational changes in India over the past three or four years. The first is that Prime Minister Narendra Modi has made lots of little changes that are bringing about action. For example, three years ago, three miles of expressway were being constructed each day. Today, it is 30 miles. Five years ago, the government wasn’t building any rural houses; now, it is building two million a year. The other change: 24 months ago, India had one of the world’s worst mobile networks. Today, it has one of the biggest, most efficient, carrying more data every day than the entirety of U.S. networks.

How can investors benefit from those changes?

Sneller: Reliance Industries[RIL.India], which started out making polyester yarn, became the biggest refinery in the world and has taken outrageous bets—most recently in mobile telephony and now, e-commerce. There are 250 million Reliance Jio [network] users, consuming six hours of phone time each day. We haven’t yet started to understand what those on-the-ground changes might mean for India’s growth over the next five, 10, or 20 years.

Leverenz: I own less in India today than in the 14 years I have been at Oppenheimer because it is overowned and overvalued. There is also this misperception that India is the next China. There is no next China—and India will never in my lifetime be even close to China. It has a big but extraordinarily poor population, and despite Modi’s efforts, it can’t make the fundamental changes that are needed.

Is Latin America becoming more attractive to investors? Mexico and Brazil have had important elections.

Leverenz: I am more interested in Mexico. I suspect that President-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s [leftist] government, elected this summer, is going to be more pragmatic than expected, and Mexican stocks are as cheap as they have been in 20 years. My fund has a large position in Femsa [ Fomento Económico Mexicano; FMX]; half of the value of the company is Coca-Cola Femsa[KOF], but Femsa also owns the convenience-store chain Oxxo, which is expanding into small pharmacies. Oxxo could become the biggest logistics company in Mexico, using its convenience stores for package delivery and using its warehousing, fulfillment, and trucking operations. That is in embryonic stages but could be a big opportunity over the next five to 10 years.

Geritz: Brazilian valuations are middling; Mexico looks better. Wal-Mart de Mexico[WMMVY] has a great balance sheet, dominates the market with a valuable network of brands, and has scale that makes others compete on price. It provides protection if the U.S. stays strong and other emerging markets don’t spring back immediately. One reservation: It is seeing abnormally strong same-store sales due to remittances from U.S. workers back home. I worry about what happens if the U.S. economy slows. You might get a better price for the stock if the market sells off. We own it; long run, it is a great company and quality compounder.

Pro-business candidate Jair Bolsonaro won the first round of presidential elections in Brazil. What is the outlook for Brazil?

Sneller: If Bolsonaro wins the runoff election, new possibilities emerge. I have one stock idea in a universally hated category: Petrobras[ Petróleo Brasileiro; PBR].

Leverenz: That’s the boldest statement we have heard so far—the most highly indebted company on Earth, and with huge governance problems.

Sneller: People haven’t fully appreciated the scale and growth potential of its sub-salt oil discoveries, which went from producing almost nothing 20 years ago to producing two million barrels of oil a day. For the first time in its history, Petrobras becomes a serious exporter of oil. And companies are making more profits per barrel at $80 a barrel now than four or five years ago at $105 to $110 a barrel because they have cut costs. It is a hugely profitable time, even for Petrobras.

Do you favor any other energy stocks?

Leverenz: Novatek[NVTK.Russia] is one of the few Russian companies I would invest in. Its management is arguably the best globally. Novatek transformed from a scrappy exploration-and-production company five years ago to the second-largest domestic gas producer. It got creative with technology and discovered condensate, essentially a wet gas that is more profitable than domestic gas. They just started shipping liquefied natural gas. We are at the beginning of a massive LNG revolution as China and other parts of North Asia want a reliable, economic source of clean energy.

Sticking with contrarian ideas, is it time to invest in Turkey?

Leverenz: I don’t think so. Turkey needs a massive recession for many years, to pare its debt and deal with its fiscal imbalances. I don’t think it is politically possible to go through that sort of protracted pain.

Sharma: The market value of the MSCI Turkey index has shrunk so much that it is only as big as the 150th-largest U.S. company. But it is hard to make a case when there are so many similar situations with better fundamentals. For example, the combined market value of three of the largest Southeast Asia economies—Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines—is the same as Apple ’s[AAPL] $1 trillion market value. The last time I saw such anomalies in small- to mid-cap stocks was in the late 1990s.

What are the danger signs emerging markets investors ought to watch for now?

Geritz: Greater-than-expected inflation that pushes interest rates higher. It would be hard in that scenario to make a case for owning many stocks anywhere in the world, when holding cash in the U.S. would get you 3% to 4%.

Sharma: One thing I’m watching is the renminbi/dollar exchange rate. Everyone is watching the 7.0 [yuan]-to-the-dollar level. The Chinese currency could weaken beyond that, but it’s the speed and circumstances around any weakening that will be important. Hopefully, China can contain [the situation] with capital controls, and has a slowdown rather than something more sinister. But that is the risk that keeps me awake.

Geritz: It used to be that if the U.S. sneezed, the world caught a cold. But China is such a large economy now that it impacts not just other emerging markets, such as Vietnam, but everyone. A slowdown in Chinese consumption—signs of which we are beginning to see—would impact global companies like Nike[NKE] or Adidas[ADS.Germany], while a slowdown in Chinese tourism would slow the growth of Japanese companies we own.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario