ECB Succession Race Tests German Faith in Bundesbank Model

With jockeying under way for top posts in central bank and EU posts, Berlin debates whether to lobby for inflation hawk Jens Weidmann

By Tom Fairless

Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann, left, is a leading candidate to replace European Central Bank President Mario Draghi, at right. Photo: shawn thew/epa-efe/rex/shutterst/EPA/Shutterstock

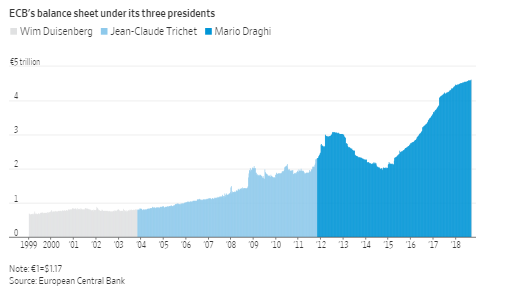

FRANKFURT—The race to succeed Mario Draghi as European Central Bank president presents Germany with a stark choice: Back the country’s own candidate, a foe of Mr. Draghi’s 2.5-trillion-euro bond-buying program, or concede that once-unorthodox monetary tools are here to stay.

Germany’s central bank, long a powerful voice in the global fight against inflation, has grown out of sync in the postfinancial crisis era of stagnant prices and wages, with its greatly expanded role for central banks and outside-the-box policies.

“Perhaps the sands have shifted,” said Stefan Gerlach, former deputy governor of Ireland’s central bank. “Having been on the wrong side of history, at least as it appears now, has not helped the Germans.”

Now, with the jockeying among European capitals already under way, Berlin must decide in the coming months whether to endorse Jens Weidmann, president of Germany’s central bank, who has likened printing money to the devil and testified against Mr. Draghi’s crisis-era bond program in a German court.

Backing Mr. Weidmann—even if it provokes a veto from countries like France and Italy, where he is already a controversial figure—would show that Germany stands by the philosophy that central banks’ primary responsibility should be to keep inflation low and avoid printing money to buy government debt.

“The political price for Jens Weidmann is high…because he has shown open criticism to some ECB policies,” said Isabel Schnabel, a member of the German Council of Economic Experts.

Mr. Draghi steps down as head of the ECB next autumn, but the race to succeed him is unofficially under way. A handful of officials have publicly flirted with the idea, although no candidate has openly declared an interest.

As the biggest economy in Europe, Germany should have outsize influence in deciding the central-bank chief for the next eight-year term. But the selection will be part a grand bargain among EU members over top European Union jobs, including the head of the European Commission, a fact that is complicating German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s equation. German officials say the government hasn’t decided whether to support Mr. Weidmann or focus on another top EU post.

Installing Mr. Weidmann could bring dividends domestically. Conservatives in Ms. Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union say they badly need a German ECB president to boost their credentials among voters worried about low rates, inflation and a central bank they think is bankrolling profligate governments in Southern Europe.

Mr. Weidmann, a former economic adviser to Ms. Merkel, has sparred with Mr. Draghi over the best way to address Europe’s economic woes. He has attacked the Italian’s policy of large-scale bond purchases, and resisted Mr. Draghi’s effort to tilt the ECB away from the Bundesbank principles it was modeled on, to be more like the U.S. Federal Reserve, which bought vast sums of U.S. debt after the financial crisis.

Mr. Weidmann has compared central-bank bond buying to a drug. In 2012, he used the devil from German literary classic, Goethe’s “Faust,” to rail against printing money, just weeks after Mr. Draghi’s now-famous pledge to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro. He has, however, backed many other ECB polices, including negative interest rates.

Most economists say Mr. Draghi’s policies supported growth and helped create millions of jobs. The bond-purchase program, known as quantitative easing, lowered bond yields in Italy and other struggling euro members. The bloc’s growth outpaced the U.S. over the past two years, and while inflation has risen, it remains around the ECB’s 2% target, despite concerns in Germany that easy money could lead to much higher levels of inflation

Critics like Mr. Weidmann charge that the polices took pressure off members to reform their economies. And some of the German central banker’s concerns about bond-buying being addictive have some backing in the numbers. The ECB initially said it would purchase €1.1 trillion of debt and end its bond-buying program two years ago. But the ECB has now bought €2.5 trillion of bonds, and won’t end the program until December at the earliest.

Unwinding that program, and phasing other ECB stimulus measures at a time when the region’s economy appears to be softening, will be the biggest task facing the next ECB president.

Mr. Draghi insists that buying government bonds will remain “part of the toolbox.”

“It’s a new instrument of monetary policy that will be used for contingencies that we don’t see now,” he said in June. ECB officials that favored quantitative easing the first time around would be more apt than Mr. Weidmann to reach for that tool again in case of emergency.

For his part, Mr. Weidmann hasn’t backed down, though he has softened his language. “I’m much more cautious about using government bond purchases, much more skeptical than many of my colleagues may be,” he said in February.

A senior lawmaker with Ms. Merkel’s conservative said he would have “qualms” about giving up on installing Mr. Weidmann at the ECB’s top, warning that the eurozone debt crisis wasn’t over.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario